An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Lactose Intolerance in Adults: Biological Mechanism and Dietary Management

Yanyong deng, benjamin misselwitz.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected] ; Tel.: +41-791934795.

Received 2015 Jul 14; Accepted 2015 Sep 14; Collection date 2015 Sep.

This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ).

Lactose intolerance related to primary or secondary lactase deficiency is characterized by abdominal pain and distension, borborygmi, flatus, and diarrhea induced by lactose in dairy products. The biological mechanism and lactose malabsorption is established and several investigations are available, including genetic, endoscopic and physiological tests. Lactose intolerance depends not only on the expression of lactase but also on the dose of lactose, intestinal flora, gastrointestinal motility, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and sensitivity of the gastrointestinal tract to the generation of gas and other fermentation products of lactose digestion. Treatment of lactose intolerance can include lactose-reduced diet and enzyme replacement. This is effective if symptoms are only related to dairy products; however, lactose intolerance can be part of a wider intolerance to variably absorbed, fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPs). This is present in at least half of patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and this group requires not only restriction of lactose intake but also a low FODMAP diet to improve gastrointestinal complaints. The long-term effects of a dairy-free, low FODMAPs diet on nutritional health and the fecal microbiome are not well defined. This review summarizes recent advances in our understanding of the genetic basis, biological mechanism, diagnosis and dietary management of lactose intolerance.

Keywords: lactose intolerance, lactase deficiency, lactose malabsorption, FODMAP, genetic test, hydrogen breath test, irritable bowel syndrome

1. Lactose and Lactase

Lactose is a disaccharide consisting of galactose bound to glucose and is of key importance in animal life as the main source of calories from milk of all mammals, all except the sea lion. Intestinal absorption of lactose requires hydrolysis to its component monosaccharides by the brush-border enzyme lactase. From week 8 of gestation, lactase activity can be detected at the mucosal surface in the human intestine. Activity increases until week 34 and lactase expression is at its peak by birth. The ability to digest lactose during the period of breast-feeding is essential to the health of the infant as demonstrated by congenital lactase deficiency that is fatal if not recognized very early after birth. However, following the first few months of life, lactase activity starts to decrease (lactase non-persistence). In most humans, this activity declines following weaning to undetectable levels as a consequence of the normal maturational down-regulation of lactase expression [ 1 ]. The exceptions to this rule are the descendants of populations that traditionally practice cattle domestication maintain the ability to digest milk and other dairy products into adulthood. The frequency of this “lactase persistence trait” is high in northern European populations (>90% in Scandinavia and Holland), decreases in frequency across southern Europe and the Middle East (~50% in Spain, Italy and pastoralist Arab populations) and is low in Asia and most of Africa (~1% in Chinese, ~5%–20% in West African agriculturalists); although it is common in pastoralist populations from Africa (~90% in Tutsi, ~50% in Fulani) [ 2 ].

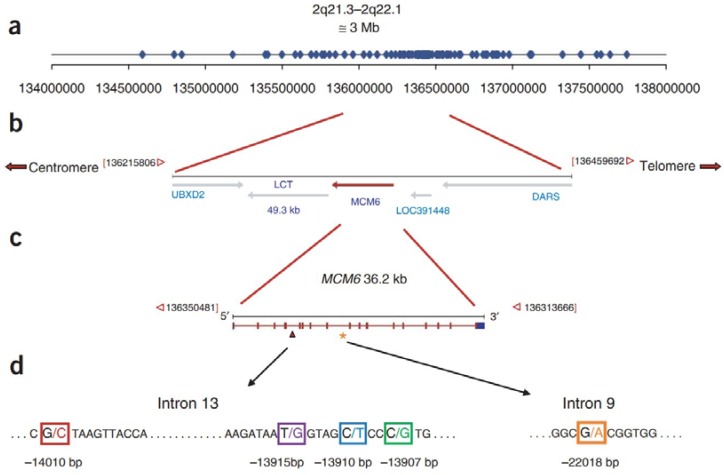

2. Genetics of Lactase Persistence

Lactase persistence is thought to be related to the domestication of dairy cattle during the last 10,000 years. Lactase persistence is inherited as a dominant Mendelian trait [ 3 ]. Adult expression of the gene encoding lactase (LCT), located on 2q21 appears to be regulated by cis -acting elements [ 4 ]. A linkage disequilibrium (LD) and haplotype analysis of Finnish pedigrees identifies two single single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with the lactase persistence trait: C/T-13910 and G/A-22018, located ~14 kb and ~22 kb upstream of LCT, respectively, within introns 9 and 13 of the adjacent minichromosome maintenance 6 (MCM6) gene [ 3 ]. The T-13910 and A-22018 alleles are 100% and 97% associated with lactase persistence, respectively, in the Finnish study, and the T-13910 allele is ~86%–98% associated with lactase persistence in other European populations [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. The genotype in China is C/C-13910, and no SNP associated with lactase persistence has been identified in the lactase gene regulatory sequence [ 8 , 9 ]. However, there are several lactase gene single nucleotide polymorphisms of this kind in other populations. Lactase persistence is mediated by G-13915 in Saudi Arabia [ 10 ], in African tribes by the G-14010, G-13915, and G-13907 polymorphism ( Figure 1 ) [ 11 , 12 ]. Thus, lactase persistence developed several times independently in human evolution in different areas of the world [ 11 ]. Multiple independent variants have allowed various human populations to quickly modify LCT expression and have been strongly conserved in adult milk-consuming populations, emphasizing the importance of regulatory mutations in recent human evolution [ 13 ]. In adult patients with homozygous lactase persistence, enzyme levels at the jejunal brush border are 10-times higher than for patients with homozygous non-persistence, and heterozygous individuals [ 14 ].

Map of the lactase (LCT) and minichromosome maintenance 6 (MCM6) gene region and location of genotyped single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). ( a ) Distribution of 123 SNPs included in genotype analysis; ( b ) map of the LCT and MCM6 gene region; ( c ) map of the MCM6 gene; and ( d ) location of lactase persistence-associated SNPs within introns 9 and 13 of the MCM6 gene in African and European populations [ 12 ].

3. Biological Mechanism of Lactose Intolerance

About two thirds of the World’s population undergoes a genetically programmed decrease in lactase synthesis after weaning (primary lactase deficiency) [ 15 , 16 ]. Additionally, in individuals with lactase persistence the occurrence of gastrointestinal infection, inflammatory bowel disease, abdominal surgery and other health issues can also cause a decrease in lactase activity (secondary lactase deficiency). Both conditions must be distinguished from congenital lactase deficiency, which is an extremely rare disease of infancy with approximately 40 cases having been reported, mainly in Finland [ 2 ].

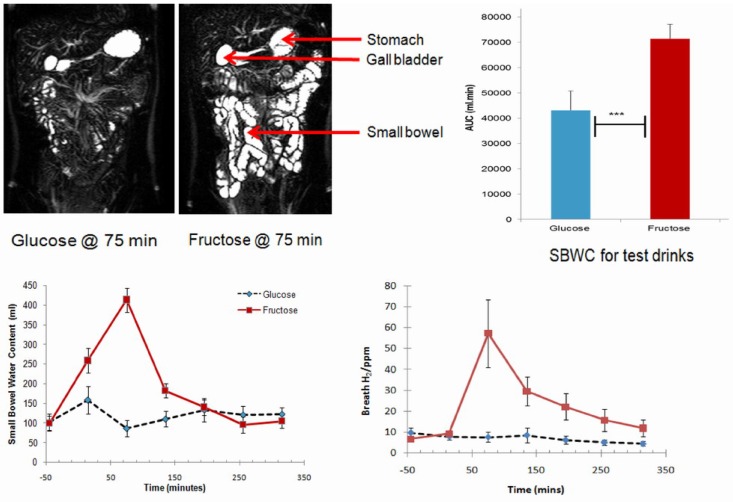

Whatever the cause, lactase deficiency results in unabsorbed lactose being present in the intestinal tract, which has effects that can lead to symptoms of lactose intolerance in susceptible individuals [ 17 ]. First, the increased osmotic load increases the intestinal water content. Second, lactose is readily fermented by the colonic microbiome leading to production of short chain fatty acids and gas (mainly hydrogen (H 2 ), carbon dioxide (CO 2 ), and methane (CH 4 )). These biological processes are present also for other poorly-absorbed, fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) that are ubiquitous in the diet [ 18 , 19 ]. Double-blind, cross-over studies in healthy volunteers applied scintigraphy or magnetic resonance imaging to document oro-cecal transit time together with breath testing to assess fermentation of the substrate. Fructose (a disaccharide similar to lactose) was seen to increase small bowel water, accelerate oro-caecal transit time (OCTT) and trigger a sharp increase in breath hydrogen production ( Figure 2 ), whereas 30 g glucose (a well-absorbed control) had no effect [ 20 , 21 ]. It should be noted that these effects are seen for poorly-absorbed, fermentable disaccharides both in health and in patients with gastrointestinal disease [ 22 , 23 , 24 ]. Long-chain carbohydrates (e.g., fructans, cellulose (“dietary fiber”)) that are not digested or absorbed by the small intestine have less impact on small bowel transit than short-chain carbohydrates; however, fermentation of this material in the large bowel produces similar effects on colonic function [ 21 ].

Small bowel water content (SBWC) and breath hydrogen (H2) concentrations after drinking each of the drinks: glucose and fructose. The time of drinking ( t = 0 min) is highlighted in the chart. Values of SBWC are mean volume (mL) ± s.e.m (standard error of mean). Values of H2 are mean concentration (p.p.m.) ± s.e.m. Figure modified from Murray et al . [ 21 ].

Malabsorption is a necessary precondition for lactose or FODMAP intolerance; however, the two are not synonymous and the causes of symptoms must be considered separately [ 25 ]. The threshold for dietary lactose tolerance is dependent on several factors including the dose consumed, residual lactase expression [ 2 ], ingestion with other dietary components [ 26 ], gut-transit time, small bowel bacterial overgrowth [ 22 , 23 ], and also composition of the enteric microbiome (e.g., high vs. low fermenters, hydrogen vs. methane producers) [ 25 , 27 , 28 , 29 ]. In addition to these environmental and physiological factors, it has been shown that patients with irritable bowel syndrome are at particular risk of both self-reporting dairy intolerance [ 9 , 30 ] and experiencing symptoms after lactose and FODMAP ingestion [ 31 , 32 ].

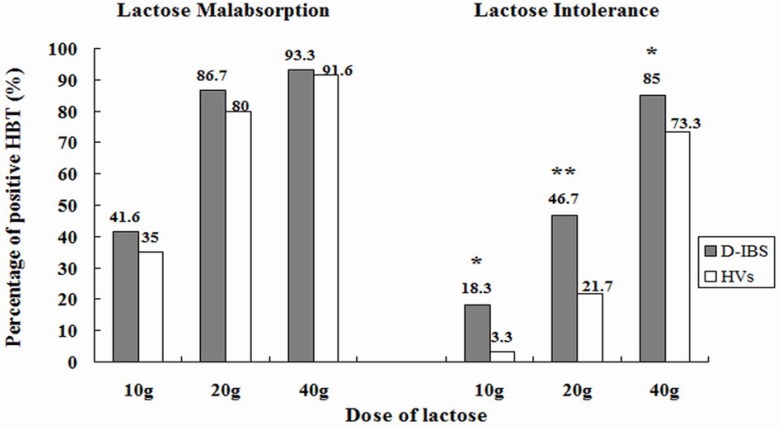

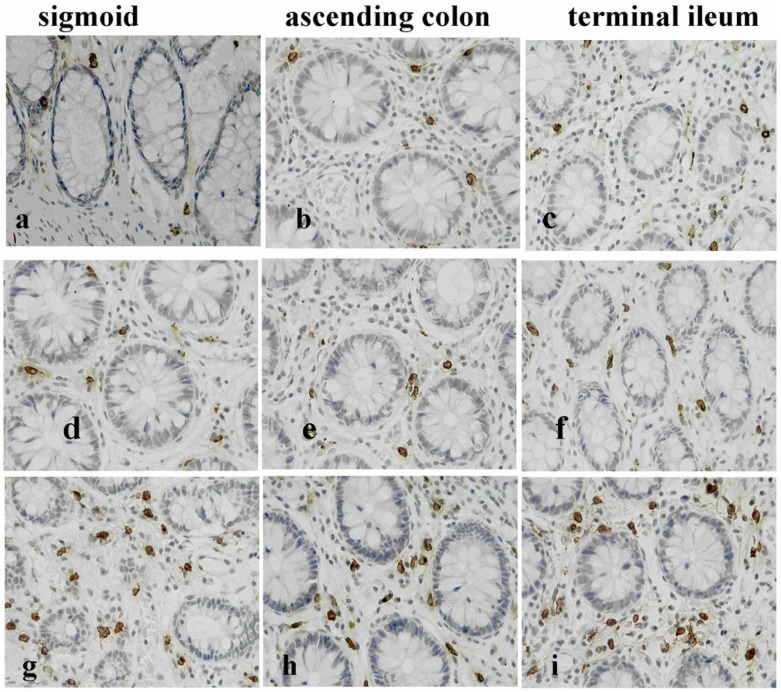

Symptoms of lactose intolerance generally do not occur until there is less than 50% of lactase activity. Regular lactose intake may also have an effect. Although lactase expression is not up-regulated by lactose ingestion, tolerance could be induced by adaptation of the intestinal flora [ 26 ]. Further, most people with lactase non-persistence can tolerate small amounts of lactose (less than 12 g, equivalent to one cup), especially when it is combined with other foods or spread throughout the day [ 26 , 33 ]. A double-blinded, randomized, three-way cross over comparison of lactose tolerance testing at 10 g, 20 g and 40 g lactose was performed in patients with diarrhea predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D) and controls in a Chinese population with lactase deficiency [ 31 ]. The study design included a dose below normal symptom threshold (10 g), plus a dose reflecting normal intake at a single meal (20 g) and a “positive control” such as that used in epidemiological trials (40 g). The multiple-dose method ( Figure 3 ) not only demonstrates the effect of dose in both study groups, but also guides nutritional management in a given patient. Importantly, the risk of symptoms in this study was greatly increased in IBS-D patients, especially at low-moderate doses found in the diet [ 31 ]. Indeed, few healthy controls with lactase non-persistence reported gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms except at the 40 g lactose dose [ 31 ]. IBS patients are known to be more sensitive to a variety of dietary and physical interventions that distend the GI tract [ 34 ]. Further studies in the same Chinese population demonstrated that anxiety, visceral hypersensitivity (defined by rectal barostat) and high-levels of gas production on breath tests are associated with patient reports of symptoms after ingestion of a modest (20 g) dose of lactose [ 35 ]. Heightened sensitivity to distension was associated with abdominal pain, bloating and overall symptom severity. Excessive gas production contributed to digestive symptoms, especially bloating and borborygmi [ 35 ]. Very interestingly, the same group of IBS patients that had lactose intolerance on hydrogen breath testing also had heightened activity of the innate mucosal immune system with increased counts of mast cells, intraepithelial lymphocytes and enterochrommafin cells in the terminal ileum and right colon ( Figure 4 ), with release of pro-inflammatory cytokines after lactose ingestion [ 36 ]. These observations are similar to those seen in patients with post-infective IBS and provide insight into the pathophysiological basis of food intolerance [ 37 ].

Prevalence of lactose malabsorption (LM) and lactose intolerance (LI) in patients with diarrhea predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D) and controls at 10-, 20-, and 40-g lactose hydrogen breath test (HBTs). * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01 [ 31 ].

Representative photomicrographs showing tryptase positive mast cells (MCs) in the colonic mucosa of a healthy control (HCs) ( a – c ); an diarrhea predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D) patient with lactose malabsorption (LM) ( d – f ) and a patient with lactose intolerance (LI) ( g – i ). IBS-D patients with LI had increased mucosal MCs compared with LM and HCs [ 36 ].

Another condition that may play a role in food tolerance is small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) caused by abnormally high bacterial counts in the small intestine, exceeding 10 5 organisms/mL [ 38 ]. SIBO is clinically characterized by bloating, abdominal discomfort and diarrhea, symptoms that are very comparable to those of lactose intolerance [ 39 ]. Bacterial fermentation of lactose with production of short-chain fatty acids and gas in the small bowel may be particularly likely to trigger abdominal symptoms. Consistent with this hypothesis, combined scintigraphy and breath test studies showed a higher prevalence of SIBO in IBS patients with lactose intolerance than in the lactose malabsorption control group [ 22 ]. This effect appeared to be independent of oro-caecal transit time and visceral sensitivity [ 22 ].

4. Clinical Diagnosis of Lactose Malabsorption and Intolerance

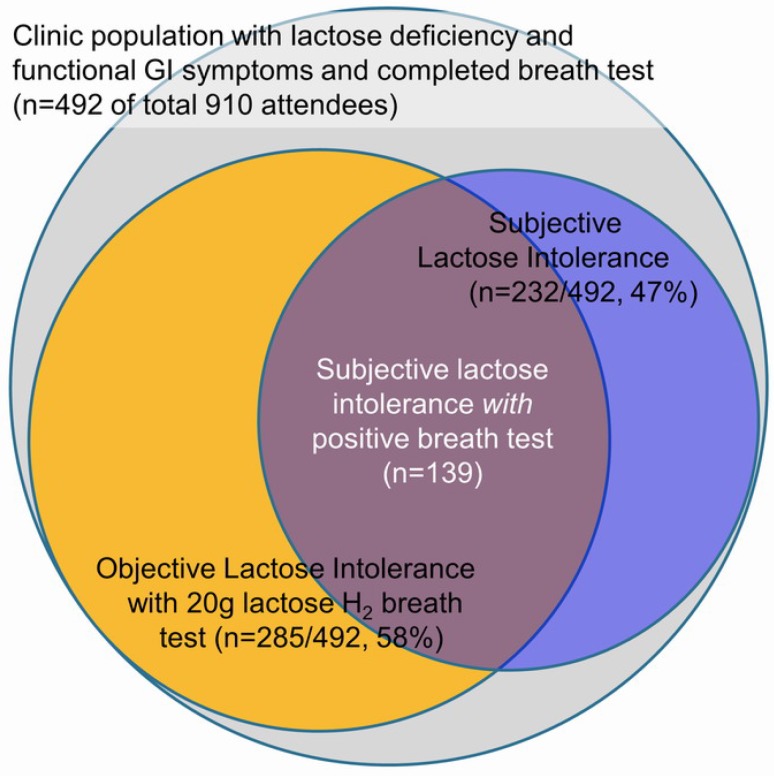

Problems with lactose absorption have been described, detected and diagnosed in several ways and this can lead to confusion among doctors and patients [ 26 ]. Lactase deficiency is defined as markedly reduced brush-border lactase activity relative to the activity observed in infants. Lactose malabsorption occurs when a substantial amount of lactose is not absorbed in the intestine. Because lactose malabsorption is nearly always attributable to lactase deficiency, the presence of this condition can be inferred from measurements of lactose malabsorption such as an increase of glucose in the blood or an increase of hydrogen in the breath. The term lactose intolerance is defined by patient reports of abdominal pain, bloating, borborygmi, and diarrhea induced by lactose. Less often it can present with nausea or constipation and a range of systemic symptoms, including headaches, fatigue, loss of concentration, muscle and joint pain, mouth ulcers, and urinary difficulties [ 40 , 41 ]; however, it is unclear whether these atypical symptoms are directly due to lactose ingestion, or related to the presence of so-called “functional diseases”, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which is often accompanied by multiple somatic complaints. Certainly, it is not possible to make a definitive diagnosis on clinical presentation alone because double-blind trials have shown that the association of self-reported lactose intolerance and the occurrence of symptoms after lactose ingestion are very poor [ 42 ], even in patients with lactase deficiency ( Figure 5 ) [ 9 ].

Lack of agreement between objective and subjective assessment of lactose intolerance [ 9 ].

There are various methods ( Table 1 ) for diagnosing lactose malabsorption and intolerance [ 25 ]. Testing of lactase activity in mucosal biopsies from the duodenum is regarded as the reference standard for primary and secondary lactase deficiency [ 43 ], however, limitations include the inhomogeneous expression of lactase [ 44 ] and the invasiveness of the test. Genetic tests may be useful for identifying lactase persistence in some European populations as the T-13910 allele is ~86%–98% associated with lactase persistence in European populations [ 5 , 6 , 7 ], however other SNPs are present in Arabian and African populations [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Future genetic tests will likely cover a range of genetic polymorphisms, potentially eliminating this limitation. A further limitation of both biopsy and genetic tests is that no assessment of symptoms is made. This impacts on the clinical relevance of these investigations because, as addressed above, only a proportion of patients with lactase deficiency develop abdominal symptoms after ingesting lactose [ 31 ].

Summary of tests for lactose malabsorption and lactose tolerance [ 25 ].

Lactose digestion and the association of maldigestion with symptoms can be assessed by the H 2 -breath test [ 45 ] and the lactose tolerance test [ 46 ]; however, the former is confounded by fluctuations of postprandial blood sugar. The H 2 -breath test can be false positive in the presence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth; however, a larger problem is false-negative tests due to the presence of hydrogen non-producing bacteria in the colon (2%–43%) [ 17 ]. This problem of “hydrogen non-production” can be mitigated to some extent by examining patient reports of symptoms after the test dose. Patients with “false positive” breath tests complain of symptoms directly after ingestion. Those with “true positive” lactose intolerance complain of symptoms only after the substrate has entered the colon (usually 50–100 min). Another possibility is to combine the biopsy or genetic test (in Caucasians) with the H 2 -breath test; however, this is an expensive and time-consuming approach.

5. Treatment of Lactose Intolerance

Treatment of lactose intolerance should not be primarily aimed at reducing malabsorption but rather at improving gastrointestinal symptoms. Restriction of lactose intake is recommended because in blinded studies patients with self-reported lactose intolerance, even those with IBS, can ingest at least 12 g lactose without experiencing symptoms [ 26 , 47 ]. Even larger doses (15 to 18 g lactose) appear to be tolerated when dairy products are taken with other nutrients [ 26 ]. One retrospective case review reported improvement of abdominal discomfort, with lactose restriction in up to 85% of IBS patients with lactose malabsorption [ 48 ]; however, prospective studies show that lactose restriction alone is not sufficient for effective symptom relief in functional GI disease [ 49 ]. In our experience this approach is effective if symptoms are related only to dairy products; however, in IBS patients, lactose intolerance tends to be part of a wider intolerance to poorly absorbed, fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPs) [ 9 , 30 ]. Evidence from recent trials indicates that this is present in about half of patients with IBS and this group requires not only restriction of lactose intake, but also a low FODMAP diet to improve gastrointestinal complaints. An initial controlled trial of a diet low in FODMAPs reported symptom improvement in 86% of IBS patients, compared to 49% for a standard dietary intervention [ 50 ]. Three randomized controlled trials have confirmed that a low FODMAP diet can benefit a wide range of symptoms in IBS patients [ 32 , 51 , 52 ]. All these studies included lactose restriction in the early “strict” phase of the dietary intervention; however, the specific role of lactose in causing symptoms was not assessed. A major issue with almost all dietary intervention trials is that the contribution of individual components (e.g. lactose) is difficult to assess as other dietary components (e.g., fat [ 53 ]) can also produce symptoms and, potentially, confound results.

Lactase enzyme replacement is another important approach in patients with “isolated” lactose intolerance that wish to enjoy dairy products. One double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study shows that in lactose malabsorbers with intolerance, lactase obtained from Kluyveromyces lactis represents a valid therapeutic strategy, with objective and subjective efficacy and without side effects [ 54 ]. Exogenous lactase obtained from Aspergillus oryzae or from Kluyveromyces lactis breaks down lactose into glucose and galactose to allow an efficient absorption [ 55 ].

A related strategy involves probiotics that alter the intestinal flora and may have beneficial effects in IBS patients [ 56 ]. Four-week consumption of a probiotic combination of Lactobacillus casei Shirota and Bifidobacterium breve Yakult improved symptoms and decreased hydrogen production in lactose intolerant patients. These effects appeared to persist for at least three months after suspension of probiotic consumption [ 56 ]. However, in another study, milk containing Lactobacillus acidophilus did not consistently reduce gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with self-reported lactose intolerance compared with control participants [ 26 ]. Further studies are required to provide high quality evidence to support or compare the efficacy of these strategies.

6. Long-Term Effects of Lactose or FODMAP Restriction

Although restricting dietary lactose or FODMAPs may improve gastrointestinal complaints, long-term effects of a diet free of dairy or FODMAPs products may be of concern [ 57 ]. Dairy products are the major source of calcium in many individuals. No study has addressed the safety and effectiveness of calcium replacement for patients with lactose intolerance; however, it seems reasonable to recommend increasing calcium intake from other foods or supplements in patients that restrict intake of dairy products, especially in the presence of other risk factors for osteoporosis.

Diet also has effects on the colonic microbiome. Altering the dietary intake of FODMAPs alter gastrointestinal microbiota [ 58 ] and a significant decrease in the concentration of probiotic bifidobacteria after four weeks of a low FODMAP diet has been reported [ 52 ]. Whether this change has any long-term implications is unknown. Recommending alternative foods is a key component of patient education and even with dietetic advice nutrient intake, in particular of calcium, can be compromised on a low lactose, low FODMAP diet.

Another issue that should be considered is the negative effect of dietary restriction on quality of life [ 9 , 59 ]. Patients with self-reported lactose intolerance restrict intake not only of dairy products but also of other foodstuffs due to general concerns about diet and health [ 9 , 59 ]. This is stressful and can be expensive as shown by the recent trend to “gluten free diets” [ 60 ]. Moreover, if not properly supervised, multiple food restrictions could lead to mal- or under-nutrition. Formal dietary intervention excludes a wide range of potential dietary triggers for a short period to achieve symptom improvement, followed by gradual food reintroduction to identify items and threshold doses that can be tolerated by patients.

7. Conclusions

Primary lactase deficiency can be regarded as the commonest “genetic disease” in the World, although, in truth, loss of lactase expression in adulthood represents the normal “wild-type” and lactase persistence the abnormal “mutant” state. Additionally, in secondary lactase deficiency, the ability to digest lactose can be lost due to infection, surgery and other insults. Whatever the cause, lactose malabsorption causes symptoms by several mechanisms: unabsorbed lactose leads to osmotic diarrhea; products of its bacterial digestion lead to secretory diarrhea and gas can distend the colon. Diagnosis of lactose malabsorption is based on detection either of the genetic mutation, loss of lactase activity in the enteric mucosa or evidence of malabsorption in the blood or breath. However, the presence of lactose malabsorption does not necessarily imply that abdominal symptoms are related to this process. The majority of healthy individuals with lactase deficiency tolerate up to 20 g lactose without difficulty. Instead, diagnosis of lactose intolerance requires concurrent assessment of lactose digestion and abdominal symptoms.

Recent studies have provided important new insight into the complex relationship between lactase deficiency, lactose malabsorption and symptom generation. This work has shed light on the wider issue of food intolerance as a cause of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome and related conditions. Understanding the biological mechanism for food intolerance to lactose and FODMAPs will help clinicians make a definitive diagnosis and guide rational dietary and medical management. Ongoing studies will provide high quality evidence to document the efficacy and long-term effects of these strategies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hua Chu for her excellent work in the Sino–Swiss trials referred to in this article. We acknowledge funding from Nestlé International that supported the Sino-Swiss trials into lactose intolerance and digestive health.

Author Contributions

Yanyong Deng and Benjamin Misselwitz researched and drafted the manuscript. Ning Dai and Mark Fox led many of the studies cited in this article, contributed to the draft manuscript and approved the final publication. All authors discussed and revised all drafts and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

Ning Dai and Mark Fox have received research funding from Nestlé International for studies of lactose intolerance. Other authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

- 1. Vesa T.H., Marteau P., Korpela R. Lactose intolerance. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2000;19(Suppl. S2):165S–175S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2000.10718086. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Swallow D.M. Genetics of lactase persistence and lactose intolerance. Ann. Rev. Genet. 2003;37:197–219. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.143820. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Enattah N.S., Sahi T., Savilahti E., Terwilliger J.D., Peltonen L., Jarvela I. Identification of a variant associated with adult-type hypolactasia. Nat. Genet. 2002;30:233–237. doi: 10.1038/ng826. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Wang Y., Harvey C.B., Pratt W.S., Sams V.R., Sarner M., Rossi M., Auricchio S., Swallow D.M. The lactase persistence/non-persistence polymorphism is controlled by a cis-acting element. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1995;4:657–662. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.4.657. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Poulter M., Hollox E., Harvey C.B., Mulcare C., Peuhkuri K., Kajander K., Sarner M., Korpela R., Swallow D.M. The causal element for the lactase persistence/non-persistence polymorphism is located in a 1 Mb region of linkage disequilibrium in Europeans. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2003;67:298–311. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-1809.2003.00048.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Hogenauer C., Hammer H.F., Mellitzer K., Renner W., Krejs G.J., Toplak H. Evaluation of a new DNA test compared with the lactose hydrogen breath test for the diagnosis of lactase non-persistence. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005;17:371–376. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200503000-00018. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Ridefelt P., Hakansson L.D. Lactose intolerance: Lactose tolerance test versus genotyping. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2005;40:822–826. doi: 10.1080/00365520510015764. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Sun H.M., Qiao Y.D., Chen F., Xu L.D., Bai J., Fu S.B. The lactase gene-13910T allele can not predict the lactase-persistence phenotype in north China. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007;16:598–601. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Zheng X., Chu H., Cong Y., Deng Y., Long Y., Zhu Y., Pohl D., Fried M., Dai N., Fox M. Self-reported lactose intolerance in clinic patients with functional gastrointestinal symptoms: Prevalence, risk factors, and impact on food choices. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2015;27:1138–1146. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12602. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Imtiaz F., Savilahti E., Sarnesto A., Trabzuni D., Al-Kahtani K., Kagevi I., Rashed M.S., Meyer B.F., Jarvela I. The T/G 13915 variant upstream of the lactase gene (LCT) is the founder allele of lactase persistence in an urban Saudi population. J. Med. Genet. 2007;44:e89. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.051631. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Ingram C.J., Elamin M.F., Mulcare C.A., Weale M.E., Tarekegn A., Raga T.O., Bekele E., Elamin F.M., Thomas M.G., Bradman N., et al. A novel polymorphism associated with lactose tolerance in Africa: Multiple causes for lactase persistence? Hum. Genet. 2007;120:779–788. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0291-1. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Tishkoff S.A., Reed F.A., Ranciaro A., Voight B.F., Babbitt C.C., Silverman J.S., Powell K., Mortensen H.M., Hirbo J.B., Osman M., et al. Convergent adaptation of human lactase persistence in Africa and Europe. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:31–40. doi: 10.1038/ng1946. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Wray G.A., Hahn M.W., Abouheif E., Balhoff J.P., Pizer M., Rockman M.V., Romano L.A. The evolution of transcriptional regulation in eukaryotes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003;20:1377–1419. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg140. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Enattah N.S., Kuokkanen M., Forsblom C., Natah S., Oksanen A., Jarvela I., Peltonen L., Savilahti E. Correlation of intestinal disaccharidase activities with the C/T-13910 variant and age. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3508–3512. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i25.3508. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Ingram C.J., Mulcare C.A., Itan Y., Thomas M.G., Swallow D.M. Lactose digestion and the evolutionary genetics of lactase persistence. Hum. Genet. 2009;124:579–591. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0593-6. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Itan Y., Jones B.L., Ingram C.J., Swallow D.M., Thomas M.G. A worldwide correlation of lactase persistence phenotype and genotypes. BMC Evol. Biol. 2010;10:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-36. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Gasbarrini A., Corazza G.R., Gasbarrini G., Montalto M., di Stefano M., Basilisco G., Parodi A., Usai-Satta P., Vernia P., Anania C., et al. Methodology and indications of H2-breath testing in gastrointestinal diseases: The Rome Consensus Conference. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009;29(Suppl. S1):1–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03951.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Magge S., Lembo A. Low-FODMAP Diet for Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;8:739–745. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Shepherd S.J., Lomer M.C., Gibson P.R. Short-chain carbohydrates and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013;108:707–717. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.96. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Madsen J.L., Linnet J., Rumessen J.J. Effect of nonabsorbed amounts of a fructose-sorbitol mixture on small intestinal transit in healthy volunteers. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2006;51:147–153. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-3100-8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Murray K., Wilkinson-Smith V., Hoad C., Costigan C., Cox E., Lam C., Marciani L., Gowland P., Spiller R.C. Differential effects of FODMAPs (fermentable oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyols) on small and large intestinal contents in healthy subjects shown by MRI. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014;109:110–119. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.386. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Zhao J., Fox M., Cong Y., Chu H., Shang Y., Fried M., Dai N. Lactose intolerance in patients with chronic functional diarrhoea: The role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010;31:892–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04252.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Zhao J., Zheng X., Chu H., Zhao J., Cong Y., Fried M., Fox M., Dai N. A study of the methodological and clinical validity of the combined lactulose hydrogen breath test with scintigraphic oro-cecal transit test for diagnosing small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in IBS patients. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2014;26:794–802. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12331. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Croagh C., Shepherd S.J., Berryman M., Muir J.G., Gibson P.R. Pilot study on the effect of reducing dietary FODMAP intake on bowel function in patients without a colon. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1522–1528. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20249. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Misselwitz B., Pohl D., Fruhauf H., Fried M., Vavricka S.R., Fox M. Lactose malabsorption and intolerance: Pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2013;1:151–159. doi: 10.1177/2050640613484463. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Shaukat A., Levitt M.D., Taylor B.C., MacDonald R., Shamliyan T.A., Kane R.L., Wilt T.J. Systematic review: Effective management strategies for lactose intolerance. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010;152:797–803. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-12-201006150-00241. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Casen C., Vebo H.C., Sekelja M., Hegge F.T., Karlsson M.K., Ciemniejewska E., Dzankovic S., Froyland C., Nestestog R., Engstrand L., et al. Deviations in human gut microbiota: A novel diagnostic test for determining dysbiosis in patients with IBS or IBD. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015;42:71–83. doi: 10.1111/apt.13236. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. He T., Priebe M.G., Zhong Y., Huang C., Harmsen H.J., Raangs G.C., Antoine J.M., Welling G.W., Vonk R.J. Effects of yogurt and bifidobacteria supplementation on the colonic microbiota in lactose-intolerant subjects. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008;104:595–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03579.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Zhong Y., Priebe M.G., Vonk R.J., Huang C.Y., Antoine J.M., He T., Harmsen H.J., Welling G.W. The role of colonic microbiota in lactose intolerance. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2004;49:78–83. doi: 10.1023/B:DDAS.0000011606.96795.40. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Bohn L., Storsrud S., Simren M. Nutrient intake in patients with irritable bowel syndrome compared with the general population. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2013;25:23–30. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12001. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Yang J., Deng Y., Chu H., Cong Y., Zhao J., Pohl D., Misselwitz B., Fried M., Dai N., Fox M. Prevalence and presentation of lactose intolerance and effects on dairy product intake in healthy subjects and patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013;11:262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.11.034. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Halmos E.P., Power V.A., Shepherd S.J., Gibson P.R., Muir J.G. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:67–75. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.09.046. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Lomer M.C., Parkes G.C., Sanderson J.D. Review article: Lactose intolerance in clinical practice—Myths and realities. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008;27:93–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03557.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Spiller R., Aziz Q., Creed F., Emmanuel A., Houghton L., Hungin P., Jones R., Kumar D., Rubin G., Trudgill N., et al. Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: Mechanisms and practical management. Gut. 2007;56:1770–1798. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.119446. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Zhu Y., Zheng X., Cong Y., Chu H., Fried M., Dai N., Fox M. Bloating and distention in irritable bowel syndrome: The role of gas production and visceral sensation after lactose ingestion in a population with lactase deficiency. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1516–1525. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.198. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Yang J., Fox M., Cong Y., Chu H., Zheng X., Long Y., Fried M., Dai N. Lactose intolerance in irritable bowel syndrome patients with diarrhoea: The roles of anxiety, activation of the innate mucosal immune system and visceral sensitivity. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014;39:302–311. doi: 10.1111/apt.12582. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Spiller R., Garsed K. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1979–1988. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.074. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Donaldson R.M., Jr. Normal Bacterial Populations of the Intestine and Their Relation to Intestinal Function. N. Engl. J. Med. 1964;270:938–945. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196404302701806. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Singh V.V., Toskes P.P. Small Bowel Bacterial Overgrowth: Presentation, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Curr. Treat. Options Gastroenterol. 2004;7:19–28. doi: 10.1007/s11938-004-0022-4. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Campbell A.K., Wann K.T., Matthews S.B. Lactose causes heart arrhythmia in the water flea Daphnia pulex. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;139:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2004.07.004. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Matthews S.B., Campbell A.K. When sugar is not so sweet. Lancet. 2000;355:1330. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02116-4. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Suarez F.L., Savaiano D.A., Levitt M.D. A comparison of symptoms after the consumption of milk or lactose-hydrolyzed milk by people with self-reported severe lactose intolerance. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333:1–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507063330101. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Newcomer A.D., McGill D.B., Thomas P.J., Hofmann A.F. Prospective comparison of indirect methods for detecting lactase deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 1975;293:1232–1236. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197512112932405. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Maiuri L., Raia V., Potter J., Swallow D., Ho M.W., Fiocca R., Finzi G., Cornaggia M., Capella C., Quaroni A., et al. Mosaic pattern of lactase expression by villous enterocytes in human adult-type hypolactasia. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:359–369. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90203-w. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Metz G., Jenkins D.J., Peters T.J., Newman A., Blendis L.M. Breath hydrogen as a diagnostic method for hypolactasia. Lancet. 1975;1:1155–1157. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(75)93135-9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Arola H. Diagnosis of hypolactasia and lactose malabsorption. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. Suppl. 1994;202:26–35. doi: 10.3109/00365529409091742. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Savaiano D.A., Boushey C.J., McCabe G.P. Lactose intolerance symptoms assessed by meta-analysis: A grain of truth that leads to exaggeration. J. Nutr. 2006;136:1107–1113. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.4.1107. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Bohmer C.J., Tuynman H.A. The effect of a lactose-restricted diet in patients with a positive lactose tolerance test, earlier diagnosed as irritable bowel syndrome: A 5-year follow-up study. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2001;13:941–944. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200108000-00011. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Parker T.J., Woolner J.T., Prevost A.T., Tuffnell Q., Shorthouse M., Hunter J.O. Irritable bowel syndrome: Is the search for lactose intolerance justified? Eur. J Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2001;13:219–225. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200103000-00001. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Staudacher H.M., Whelan K., Irving P.M., Lomer M.C. Comparison of symptom response following advice for a diet low in fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs) versus standard dietary advice in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2011;24:487–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2011.01162.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Ong D.K., Mitchell S.B., Barrett J.S., Shepherd S.J., Irving P.M., Biesiekierski J.R., Smith S., Gibson P.R., Muir J.G. Manipulation of dietary short chain carbohydrates alters the pattern of gas production and genesis of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010;25:1366–1373. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06370.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 52. Staudacher H.M., Lomer M.C., Anderson J.L., Barrett J.S., Muir J.G., Irving P.M., Whelan K. Fermentable carbohydrate restriction reduces luminal bifidobacteria and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J. Nutr. 2012;142:1510–1518. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.159285. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 53. Simren M., Abrahamsson H., Bjornsson E.S. Lipid-induced colonic hypersensitivity in the irritable bowel syndrome: The role of bowel habit, sex, and psychologic factors. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007;5:201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.032. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 54. Montalto M., Nucera G., Santoro L., Curigliano V., Vastola M., Covino M., Cuoco L., Manna R., Gasbarrini A., Gasbarrini G. Effect of exogenous beta-galactosidase in patients with lactose malabsorption and intolerance: A crossover double-blind placebo-controlled study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005;59:489–493. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602098. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 55. Ojetti V., Gigante G., Gabrielli M., Ainora M.E., Mannocci A., Lauritano E.C., Gasbarrini G., Gasbarrini A. The effect of oral supplementation with Lactobacillus reuteri or tilactase in lactose intolerant patients: Randomized trial. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2010;14:163–170. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 56. Almeida C.C., Lorena S.L., Pavan C.R., Akasaka H.M., Mesquita M.A. Beneficial effects of long-term consumption of a probiotic combination of Lactobacillus casei Shirota and Bifidobacterium breve Yakult may persist after suspension of therapy in lactose-intolerant patients. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2012;27:247–251. doi: 10.1177/0884533612440289. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 57. Wilt T.J., Shaukat A., Shamliyan T., Taylor B.C., MacDonald R., Tacklind J., Rutks I., Schwarzenberg S.J., Kane R.L., Levitt M. Lactose intolerance and health. Evid. Rep. Technol. Assess. 2010;192:1–410. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 58. Halmos E.P., Christophersen C.T., Bird A.R., Shepherd S.J., Gibson P.R., Muir J.G. Diets that differ in their FODMAP content alter the colonic luminal microenvironment. Gut. 2015;64:93–100. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307264. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 59. Bohn L., Storsrud S., Tornblom H., Bengtsson U., Simren M. Self-reported food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS are common and associated with more severe symptoms and reduced quality of life. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013;108:634–641. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.105. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 60. Farnetti S., Zocco M.A., Garcovich M., Gasbarrini A., Capristo E. Functional and metabolic disorders in celiac disease: New implications for nutritional treatment. J. Med. Food. 2014;17:1159–1164. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2014.0025. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (906.8 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Lactose intolerance.

Talia F. Malik ; Kiran K. Panuganti .

Affiliations

Last Update: April 17, 2023 .

- Continuing Education Activity

Lactose intolerance is a clinical syndrome that manifests with characteristic signs and symptoms upon consuming food substances containing lactose, a disaccharide. Normally upon lactose consumption, it is hydrolyzed into glucose and galactose by the lactase enzyme, which is found in the small intestinal brush border. Deficiency of lactase due to primary or secondary causes results in clinical symptoms. This activity describes the pathophysiology of lactose intolerance and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

- Review the pathophysiology of lactose intolerance.

- Describe the presentation of a patient with lactose intolerance.

- Summarize the management options for lactose intolerance.

- Outline the importance of improving care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by lactose intolerance.

- Introduction

Lactose intolerance is a clinical syndrome that manifests with characteristic signs and symptoms upon consuming food substances containing lactose, a disaccharide. Normally upon lactose consumption, it is hydrolyzed into glucose and galactose by the lactase enzyme, which is found in the small intestinal brush border. [1] Deficiency of lactase due to primary or secondary causes results in clinical symptoms. Disease severity varies among individuals. Lactose is present in dairy, milk products, and mammalian milk. [2] It is also sometimes referred to as lactose malabsorption.

Lactase deficiency is the commonest type of disaccharidase deficiency. Enzyme levels are at the peak shortly after birth and decline after that, despite continued lactose intake. Among the animal world, nonhuman mammals generally lose their ability to digest lactose into its components as they reach adulthood. Certain populations of the human species, such as those of South American, Asian, and African descent, tend to develop lactase deficiency. On the contrary, people of northern Europe origin or northwestern India usually retain the ability to digest lactose into adulthood. [3]

Lactose intolerance presents with abdominal bloating and pain, loose stools, nausea, flatulence, and borborygmi. [4] [5] Many people start avoiding milk as soon as a diagnosis is made, or even the suggestion of lactose intolerance is put forward. This leads to consuming specially prepared products with digestive aids, adding to the health care burden.

Lactase enzyme deficiency can occur in individuals with lower levels of this enzyme, resulting in failure to hydrolyze lactose into absorbable glucose and galactose components. There are four leading causes of lactase deficiency.

Primary Lactase Deficiency

It is the most common cause of lactase deficiency, also known as lactase non-persistence. There is a gradual decline in lactase enzyme activity with increasing age. Enzyme activity begins to decline in infancy, and symptoms manifest in adolescence or early adulthood. More recently, it has been observed that lactase non-persistence is of the ancestral form (normal Mendelian inheritance), and lactase persistence is secondary to mutation. [6] [7] [8]

Secondary Lactase Deficiency

Due to several infectious, inflammatory, or other diseases, injury to intestinal mucosa can cause secondary lactase deficiency. [9] Common causes include:

- Gastroenteritis

- Celiac disease

- Crohn disease

- Ulcerative colitis

- Chemotherapy

- Antibiotics

Congenital Lactase Deficiency

There is a decrease or absence of lactase enzyme activity since birth due to autosomal recessive inheritance. [10] [11] It manifests in the newborn after ingestion of milk. It is a rare cause of the deficiency, and its genetics are not very well known. [12]

Developmental Lactase Deficiency

It is seen in premature infants born at 28 to 37 weeks of gestation. [13] The infant's intestine is underdeveloped, resulting in an inability to hydrolyze lactose. This condition improves with increasing age due to the maturation of the intestine, which results in adequate lactase activity.

- Epidemiology

Lactose intolerance is a common disease; however, it is rare in children younger than 5. It is most often seen in adolescents and young adults. On average, 65% of the world's population is lactose intolerant. [14] The prevalence of lactose intolerance is variable among different ethnicities. It is most common in African Americans, Hispanics/Latinos, and Asians and least prevalent in people of European descent. [15] Ethnic groups with a higher prevalence of lactose intolerance also are more likely to have lactose non-persistence. [16] [17]

The primary form is the commonest (found in up to 70% of the world's population, but not all of them are symptomatic). [18] [19] [20] On the contrary, the congenital type is extremely rare (with around 40 cases reported worldwide to date). [6]

In the US, the primary disease is much more common in certain ethnicities, such as African-Americans, American Indians, Hispanics or Latinos, and Asian-Americans, than in White Americans. [21] [22] [23] [24] [21] North Americans, Australians, and White Northern Europeans have the lowest rates, ranging between 2% and 15%. [21] [22] On the contrary, the prevalence of lactose intolerance is 50% to 80% in South Americans, around 100% in American Indians and some East Asians, and around 60% to 80% in Ashkenazi Jews and Africans. [21] [23] [24]

The age-related decline in lactase activity is generally complete during childhood; however, the decline has also been seen to occur later, in adolescence, particularly in Whites. [25] The eventual level and the duration of loss of lactase expression vary considerably per ethnicity. Chinese and Japanese people lose between 80% and 90% of activity within three to four years after weaning. Jews and Asians lose 60% to 70% over many years after weaning, and for White Northern Europeans and North Americans, it could take between 18 and 20 years for lactase expression to reach its lowest levels. [18] A low prevalence of lactase non-persistence is noted in patients of mixed ethnicity, whereas an increased prevalence is observed in the native ethnic group.

The onset of the disease is generally subtle and progressive in primary illness, and many patients first experience symptoms of intolerance in late adolescence and adulthood. [2] [3] As opposed to White Northern Europeans, Australians, and North Americans, earlier presentation is noted in Native Americans, Asian-Americans, African-Americans, and Hispanics/Latinos. [21] The secondary disease is commoner in children, particularly in developing countries where infections are a common cause. [9]

The sexes are affected equally.

- Pathophysiology

The lactase enzyme is located in the brush border of the small intestinal mucosa. Deficiency of lactase results in the presence of unabsorbed lactose within the bowel. This results in an influx of fluid into the bowel lumen resulting in osmotic diarrhea. Colonic bacteria ferment the unabsorbed lactose-producing gas (hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and methane), which hydrolyzes lactose into monosaccharides. [26] This results in an additional influx of fluid within the lumen. The overall effect of these mechanisms results in various abdominal signs and symptoms.

An association has been reported between certain single nucleotide polymorphisms with lactose tolerance in a northeastern Brazilian population. In Indo-Europe, lactose intolerance is linked with rs4982235 SNP (or -13910C>T). [27]

- Histopathology

In lactose intolerance, microscopic findings of the small intestine vary depending on the cause of lactase deficiency. In primary lactase deficiency, the mucosa appears normal. Lactase activity can be measured to assess the severity of the disease. The mucosa may be abnormal in secondary lactase deficiency, depending upon the underlying cause. It helps determine the secondary causes of the disease, such as celiac disease. Biopsy results may be normal if the mucosal abnormality is focal or patchy. [28]

- History and Physical

Signs and symptoms of lactose intolerance manifest 30 minutes to 1 to 2 hours after ingesting milk (dairy) products. The severity of symptoms depends upon the amount of lactose consumed, the residual lactase function, and the small bowel transit time. [29] Common signs and symptoms may include the following:

- Abdominal bloating

- Abdominal Pain

- Nausea and vomiting

- Flatulence [30] [31]

Less commonly, it can present with headache, muscle pain, joint pain, mouth ulcers, urinary symptoms, and loss of concentration. [32] [33]

Lactose intolerance is evaluated by getting a careful history, performing a physical exam, and medical tests.

It is essential to take a past medical, family, and dietary history to determine the cause of lactose intolerance and exclude secondary causes.

Physical Exam

Assess for the presence of abdominal bloating, tenderness, and pain.

Medical Tests

- Hydrogen breath test: This test measures the hydrogen content of breath after lactose ingestion. The test is positive for lactose malabsorption if the post-lactose breath hydrogen value rises >20 ppm compared with the baseline. [34]

- Stool acidity test: Unabsorbed lactose is fermented by colonic bacteria into lactic acid, which lowers the stool pH.

- Dietary elimination: One way to assess the underlying illness is to eliminate lactose-containing food products, which would result in the resolution of symptoms. Resumption of symptoms with the reintroduction of these products will indicate lactose intolerance. [35]

- Milk tolerance test: Administer 500 mL of milk and obtain the blood glucose level. A rise in blood sugar of less than 9 mg/dL shows lactose malabsorption. [36]

- Lactose tolerance test: This test determines lactose absorption after ingestion of a lactose-containing liquid. Measure serial blood glucose levels after giving an oral lactose load. After obtaining a fasting serum glucose level, 50 g of lactose is administered. [34] Serum glucose level is then measured at 0, 60, and 120 minutes. Failure of blood glucose levels to rise by 20 g may indicate lactose intolerance. This test has a specificity of 96% and a sensitivity of 75%. False-negative results may occur in patients with diabetes or small bowel bacterial overgrowth. The results are also affected by abnormal gastrointestinal emptying. [37]

- Small bowel biopsy: This test is rarely performed as it is invasive. It is only indicated to rule out secondary causes of lactose intolerance.

- Genotyping: It is an emerging test with higher sensitivity and specificity. It has been used in Germany and the Nordic states, but it is yet not widely available or practiced elsewhere. [38]

- Treatment / Management

Management of lactose intolerance consists of dietary modification, lactase supplementation, and treating an underlying condition in people with secondary lactase deficiency.

Dietary Modification

Lactase-containing milk products and calcium supplements are recommended. Limiting the dietary intake of lactose by avoiding the intake of lactose-containing products improves the symptoms of the disease. The following products contain lactose and, therefore, must be avoided:

- Soft and processed cheese

- Pancakes and waffles

- Mashed potatoes

- Custard and pudding

Yogurt contains varying amounts of lactose and may cause symptoms in some patients. Greek yogurt has the least. Yogurt culture microorganisms can produce β-galactosidase as part of their lactose utilization pathway. This may promote lactose digestion in vivo. [39] Plant-based milk alternatives are becoming more available; however, technological issues, palatability, and nutritional balance remain concerns. [40] [41] Probiotics have been observed to improve symptoms, such as the DDS-1 strain of Lactobacillus acidophilus. [42] [43] Calcium and vitamin D supplements should also be recommended. In patients with secondary lactase deficiency, treatment should be directed at the underlying cause. [44]

Lactase Supplements

Lactase enzyme supplements contain lactase which breaks down lactose in milk and milk-containing products. They are available as lactase enzyme tablets or drops.

- Differential Diagnosis

Other conditions to be considered in the list of differential diagnoses of lactose intolerance include:

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Tropical sprue

- Cystic fibrosis

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Diverticular disease

- Intestinal Neoplasm or polyp

- Excessive ingestion of laxatives

- Viral gastroenteritis

- Bacterial infection

- Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

Emerging treatments include the following:

Fungal Beta-galactosidases

Two fungal beta-galactosidases from Aspergillus carbonarius ATCC6276 are beta-gal 1 and beta-gal 2. They can be given alone or in combination and may be used as an enzyme supplement for lactose intolerance. [45] Unlike current commercialized supplemental lactases, these purified enzymes demonstrate significant stability on exposure to simulated gastric conditions.

Nutrigenomics

Nutrigenomics may be used in the future management of hypolactasia through prompt identification of specific mutations or haplotype patterns that modulate dietary responses in affected individuals. [46]

Lactose intolerance has an excellent prognosis. Most patients have a considerable improvement in signs and symptoms with dietary modification alone. Lactose intolerant may lead to osteopenia. [47] [48] [49] Vitamin D deficiency is linked to the LCT -13910C>T gene variant of lactose intolerance among Whites. [49]

- Complications

Following are some common complications:

- Osteoporosis [15]

- Malnutrition

- Weight loss

- Growth failure

- Consultations

Once a diagnosis of lactose intolerance is made, consultation should be made with a gastroenterologist and dietician.

- Deterrence and Patient Education

Lactose-intolerant patients and their families should be advised that ingestion of lactose-containing products generally only leads to reversible symptoms without causing permanent damage to the gastrointestinal tract (unlike celiac disease). Also, there are no long-term complications if an adequate intake of proteins, calories, calcium, and vitamin D is ensured. [21]

Primary and congenital lactase deficiency can not be prevented. However, secondary lactase deficiency could be prevented if underlying secondary causes are diagnosed early and promptly instituted appropriate treatment to preserve intestinal mucosal integrity. In addition, avoiding lactose-containing foods helps limit long-term disease severity.

- Pearls and Other Issues

To avoid their use, people with lactose intolerance can check the ingredients on food labels for lactose on food products.

Some people with lactose intolerance can tolerate some milk and milk-containing products and may not need to avoid them completely.

Lactose intolerance is commonly confused with milk allergy. Lactose intolerance is a gastrointestinal disorder, while milk allergy is an autoimmune reaction against specific milk proteins. Milk allergy is life-threatening and presents early in infancy, while Lactose intolerance usually presents in adolescence or early adulthood.

Milk is rich in calcium and vitamin D. Prolong avoidance of milk in people with lactose intolerance can result in calcium and vitamin D deficiency.

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of lactose intolerance are with an interprofessional team that includes a nurse practitioner, primary care provider, pediatrician, gastroenterologist, and an allergist. Lactose intolerance is commonly confused with milk allergy. Lactose intolerance is a gastrointestinal disorder, while milk allergy is an autoimmune reaction against certain milk proteins. Milk allergy is life-threatening and presents early in infancy, while Lactose intolerance usually presents in adolescence or early adulthood. It is important to educate the patient that they should always check the ingredients on food labels for lactose on food products to avoid their use when they have lactose intolerance. However, some people with lactose intolerance can tolerate some milk and milk-containing products and may not need to avoid them completely. Prolonged avoidance of milk in people with lactose intolerance can result in calcium and vitamin D deficiency. [50] [level 5]

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Click here for a simplified version.

- Comment on this article.

Disclosure: Talia Malik declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Kiran Panuganti declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Malik TF, Panuganti KK. Lactose Intolerance. [Updated 2023 Apr 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Review [Lactose intolerance and consumption of milk and milk products]. [Z Ernahrungswiss. 1997] Review [Lactose intolerance and consumption of milk and milk products]. Sieber R, Stransky M, de Vrese M. Z Ernahrungswiss. 1997 Dec; 36(4):375-93.

- Review The acceptability of milk and milk products in populations with a high prevalence of lactose intolerance. [Am J Clin Nutr. 1988] Review The acceptability of milk and milk products in populations with a high prevalence of lactose intolerance. Scrimshaw NS, Murray EB. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988 Oct; 48(4 Suppl):1079-159.

- Review Lactose intolerance. [Am Fam Physician. 2002] Review Lactose intolerance. Swagerty DL Jr, Walling AD, Klein RM. Am Fam Physician. 2002 May 1; 65(9):1845-50.

- Review Genetic variation and lactose intolerance: detection methods and clinical implications. [Am J Pharmacogenomics. 2004] Review Genetic variation and lactose intolerance: detection methods and clinical implications. Sibley E. Am J Pharmacogenomics. 2004; 4(4):239-45.

- A comparison of symptoms after the consumption of milk or lactose-hydrolyzed milk by people with self-reported severe lactose intolerance. [N Engl J Med. 1995] A comparison of symptoms after the consumption of milk or lactose-hydrolyzed milk by people with self-reported severe lactose intolerance. Suarez FL, Savaiano DA, Levitt MD. N Engl J Med. 1995 Jul 6; 333(1):1-4.

Recent Activity

- Lactose Intolerance - StatPearls Lactose Intolerance - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

A New Approach to the Study of Tolerance: Conceptualizing and Measuring Acceptance, Respect, and Appreciation of Difference

- Original Research

- Open access

- Published: 09 September 2019

- Volume 147 , pages 897–919, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Mikael Hjerm ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4203-5394 1 ,

- Maureen A. Eger ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9023-7316 1 ,

- Andrea Bohman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8335-9235 1 &

- Filip Fors Connolly 1

44k Accesses

46 Citations

26 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

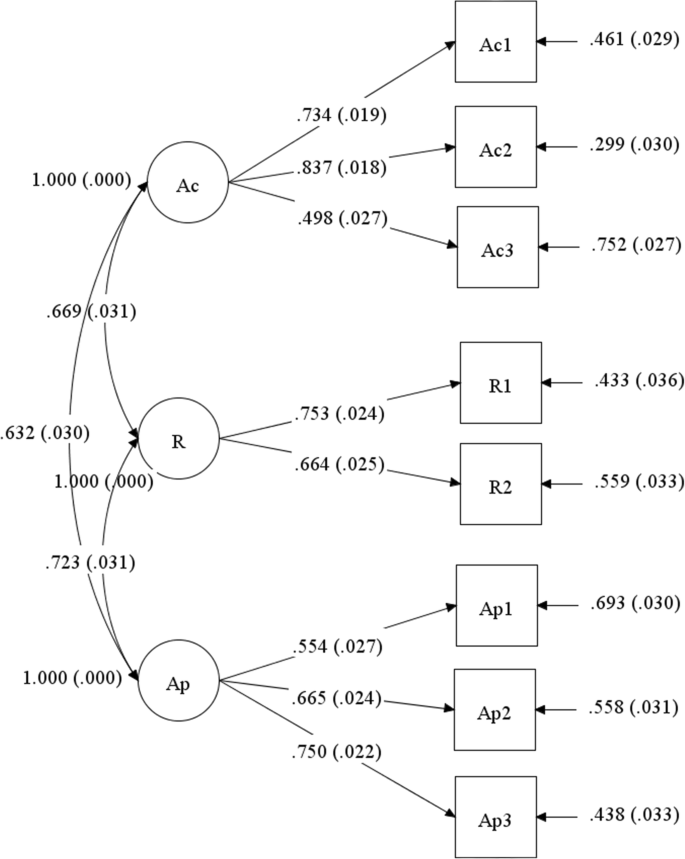

Previous empirical research on tolerance suffers from a number of shortcomings, the most serious being the conceptual and operational conflation of (in)tolerance and prejudice. We design research to remedy this. First, we contribute to the literature by advancing research that distinguishes analytically between the two phenomena. We conceptualize tolerance as a value orientation towards difference. This definition—which is abstract and does not capture attitudes towards specific out-groups, ideas, or behaviors—allows for the analysis of tolerance within and between societies. Second, we improve the measurement of tolerance by developing survey items that are consistent with this conceptualization. We administer two surveys, one national (Sweden) and one cross-national (Australia, Denmark, Great Britain, Sweden, and the United States). Results from structural equation models show that tolerance is best understood as a three-dimensional concept, which includes acceptance of, respect for, and appreciation of difference. Analyses show that measures of tolerance have metric invariance across countries, and additional tests demonstrate convergent and discriminant validity. We also assess tolerance’s relationship to prejudice and find that only an appreciation of difference has the potential to reduce prejudice. We conclude that it is not only possible to measure tolerance in a way that is distinct from prejudice but also necessary if we are to understand the causes and consequences of tolerance.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Different Faces of Social Tolerance: Conceptualizing and Measuring Respect and Coexistence Tolerance

The Refined Theory of Basic Values

Worldwide divergence of values

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Tolerance is generally understood as a necessary component of a functioning democracy and stable world order. Indeed, the Preamble of the United Nations Charter (UN 1945 ) declares the intention of its member states “to practice tolerance and live together in peace with one another as good neighbours.” Later, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO 1995 ) clarified the meaning of tolerance. According to Article 1.1., “[t]olerance is respect, acceptance and appreciation of the rich diversity of our world’s cultures, our forms of expression and ways of being human…Tolerance is harmony in difference.”

Tolerance is often invoked as something to which individuals and societies should aspire, especially given diversity, in all its forms, is increasingly a feature of contemporary democracies. When tensions arise, some leaders call for a “greater tolerance” of particular groups or encourage general efforts to become “a more tolerant society.” For example, in 2004, then Secretary-General of the UN, Kofi Annan said, “Tolerance, inter-cultural dialogue and respect for diversity are more essential than ever in a world where peoples are becoming more and more closely interconnected” (United Nations 2004 ). According to UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay, “Tolerance is an act of humanity, which we must nurture and enact each in our own lives every day, to rejoice in the diversity that makes us strong and the values that bring us together” (UNESCO 1996 ). Yet, what does this mean in practice? That those who hold prejudicial attitudes should fight against their dislike of particular out-groups? That everyone should respect others’ values or attitudes even when they are contrary to their own? That society should always value or embrace diversity? Leaders rarely give answers to these questions. Unfortunately, science does not provide much guidance either.

Over 40 years ago, Ferrar ( 1976 :63) proclaimed, “The concept of tolerance is in a state of disarray.” According to Ferrar, tolerance has multiple dimensions, but the empirically oriented literature primarily emphasizes one: negative attitudes towards out-groups. She argues that when scholars rely on indicators of prejudice towards social groups or discrimination in their analyses of tolerance, they imply that “tolerance and its opposite are sufficiently described by reference to categoric prejudgments of minority groups and their members” (p. 67). We take this argument one step further and contend that incorporating prejudice into the meaning or measurement of tolerance makes the concept of tolerance analytically indistinguishable from prejudice, confusing what tolerance is and how it differs from dislike, disapproval, or disgust with specific out-groups. Despite a great deal of empirical research on tolerance over the past 40 years, some of which includes overt efforts to clarify the concept, this disarray persists. We claim that the central problem continues to be the conflation—explicit or implicit—of prejudice and (in)tolerance, either in conceptualization or operationalization.

Despite problems in the scientific literature, it is generally accepted that tolerance is something necessary for democracies. As Kuklinski et al. ( 1991 :3) note: “Few aspects of political life so directly and immediately touch upon the daily lives of common citizens as does their tolerance toward each other.” Footnote 1 To answer some of the pressing, if not existential questions facing multiethnic, democratic societies today, we need a clearer understanding of tolerance—what it is and what it isn’t. And, before we can begin to assess its impact on various aspects of social, economic, and political life, we need better tools to measure it.

In the sections that follow, we begin with a review of previous empirical research on tolerance. Then, based on scholarship on toleration, we advance a conceptualization of tolerance that is abstract as well as analytically separate from other concepts. Specifically, we define tolerance as a value orientation towards difference . Next, we develop new measures to operationalize three aspects of tolerance. Importantly, these measures do not include references to specific social or political out-groups or particular types of attitudes or behaviors. Instead, the items capture acceptance of, respect for, and appreciation of difference in the abstract. We administer a survey twice—first using a random sample of the Swedish population and second using an online format in Australia, Denmark, Sweden, United Kingdom, and the United States. After validating our measures empirically, we demonstrate their relationship to prejudice and other variables. We conclude with a discussion of our results, their contributions, limitations, as well as practical implications.

2 Previous Approaches to the Study of Tolerance

In general, two broad conceptualizations of tolerance exist. The first approach understands tolerance as a permissive attitude towards a disliked out-group. Thus, this conceptualization begins with the notion that in order to be tolerant one first has to be prejudiced. Previous research from this tradition incorporates the dislike of out-groups into the measurement of tolerance. We critique this approach on both theoretical and methodological grounds. The second approach defines tolerance as a positive response to diversity itself. This conceptualization is analytically distinct from prejudice and lays the foundation for superior operationalization. However, previous studies that begin with this definition have nevertheless relied on measures of prejudice in their analyses, which means our understanding of tolerance remains limited. Thus, our critique of this approach is primarily methodological. In the sections that follow, we examine these approaches to tolerance in greater detail and discuss their theoretical and empirical implications.

2.1 Tolerance as Phenomenon Dependent on Prejudice

The first conceptualization of tolerance can be summarized as: Person X is tolerant if Person X dislikes Person Y doing Z. Person X has the means to prevent Person Y from doing Z, but Person X refrains from doing so. Therefore, in order to tolerate someone or something, one first needs to experience disapproval or dislike, and then despite these negative sentiments exhibit permissiveness or acceptance. Tolerance in this sense implies “forbearance” or the readiness to “put up with” with what one dislikes (Rapp and Freitag 2015 ; Robinson et al. 2001 ; Sullivan et al. 1979 ; Verkuyten and Slooter 2007 ).

To “put up with” in political terms translates into allowing the expression of objectionable ideas (Sullivan et al. 1979 ), or more specifically, to extend social rights related to political participation and freedom of speech to groups one dislikes or disagrees with (Mondak and Sanders 2005 ; Rapp 2017 ). The “objection criteria” is at the core of this conceptualization, as “… one cannot tolerate ideas of which one approves (Gibson 2006 , p. 22).” Tolerance, in this sense, is a sequential or twofold concept (Rapp and Freitag 2015 ), where the crux of the matter is the initial position of like or dislike.

This understanding of tolerance is theoretically problematic for two reasons. First, by this definition, the existence of tolerance depends on the existence of prejudice. People who are not prejudiced are incapable of being tolerant let alone becoming more tolerant. Moreover, we can only gauge if society has become more tolerant by knowing if a society has become less prejudiced. Second, this definition excludes reactions to the mere existence of out-groups. In theory, an individual must have the capacity to prevent what is disliked in order to demonstrate tolerance. Because the presence of racial and ethnic out-groups is likely beyond any one person’s control, it becomes theoretically impossible to be tolerant of this type of diversity. Beyond these theoretical shortcomings, we also argue that this understanding of tolerance necessarily leads to the empirical conflation of tolerance and prejudice.

Many empirical studies of tolerance begin with the assumption that particular groups are widely disliked or, at the very least, viewed with skepticism (Bobo and Licari 1989 ; van Doorn 2016 ; Gibson and Bingham 1982 ; Gibson 1998 ). An important example is Stouffer’s ( 1955 ) seminal work on tolerating non-conformity (e.g., socialism and atheism) in the United States. In his study, examples of tolerance include the willingness to extend rights such as freedom of speech to these “non-conformist” groups. Verkuyten and Slooter ( 2007 ) study tolerance of Muslim beliefs and practices among Dutch teenagers. They motivate their choice of out-group with reference to the general status of Islam in Dutch society. The main issue with this “unpopular groups” strategy is that it is impossible to distinguish empirically between people who support rights for groups they dislike and people who support rights because they are positively disposed towards the group in question (Sullivan et al. 1979 ).

Sullivan et al. ( 1979 ) introduce the “least-liked” approach in part to avoid contaminating the measurement of tolerance with respondents’ attitudes towards specific groups. As they put it: “If we had merely asked all respondents whether communists should be allowed to hold public office, their responses would depend not only on their levels of tolerance, but also on their feelings toward communists” (p. 785). To establish initial dislike, Sullivan et al. ( 1979 ) measure respondents’ attitudes about various groups in society. After identifying a disliked, or least liked, group, the respondents report preferences regarding these group members’ participation in political and civic activities. Adopting the same strategy, Rapp ( 2017 ) first examines respondents’ attitudes towards groups that are ethnically, religiously, or culturally diverse from them. Anti-immigrant attitudes constitute the rejection component. She then restricts her sample only to those respondents who are prejudiced, because theoretically, they are the only ones who can be tolerant.

We argue that neither strategy truly captures tolerance, because in both prejudice remains fundamental to the measurement of tolerance. Footnote 2 Thus, regardless of whether dislike is assumed, as in the unpopular group strategy, or measured, as in the least liked approach, empirical findings actually reflect respondents’ attitudes towards an out-group.

In summary, this first approach to the study of tolerance treats prejudice as a prerequisite for tolerance. Footnote 3 If dislike of an out-group is a precondition for tolerance, this means that in theory one cannot be tolerant without having been prejudiced at some earlier point in time. Conceptually there is a great deal of overlap between prejudice and tolerance, which inevitably extends to the measurement of tolerance (e.g., Kuklinski et al. 1991 ; Davis 1995 ; Gibson 1998 ; Verkuyten and Slooter 2007 ; Rapp and Ackermann 2016 ).

2.2 Tolerance as a Phenomenon Distinct from Prejudice

A second approach to analyzing tolerance does not begin with dislike of groups and instead focuses on subjective reactions to the existence of diverse values, behaviors, and lifestyles. Kirchner et al. ( 2011 :205) define tolerance as “the willingness to tolerate or accept persons or certain groups as well as their underlying values and behavior by means of a co-existence (even if they are completely different from one’s own).” Norris ( 2002 :158) defines tolerance as “the willingness to live and let live, to tolerate diverse lifestyles and political perspectives.” Dunn et al. ( 2009 :284) define tolerance “as a non-negative general orientation toward groups outside of one’s own.”