- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 04 February 2020

Marijuana legalization and historical trends in marijuana use among US residents aged 12–25: results from the 1979–2016 National Survey on drug use and health

- Xinguang Chen 1 ,

- Xiangfan Chen 2 &

- Hong Yan 2

BMC Public Health volume 20 , Article number: 156 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

112k Accesses

82 Citations

81 Altmetric

Metrics details

Marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug in the United States. More and more states legalized medical and recreational marijuana use. Adolescents and emerging adults are at high risk for marijuana use. This ecological study aims to examine historical trends in marijuana use among youth along with marijuana legalization.

Data ( n = 749,152) were from the 31-wave National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 1979–2016. Current marijuana use, if use marijuana in the past 30 days, was used as outcome variable. Age was measured as the chronological age self-reported by the participants, period was the year when the survey was conducted, and cohort was estimated as period subtracted age. Rate of current marijuana use was decomposed into independent age, period and cohort effects using the hierarchical age-period-cohort (HAPC) model.

After controlling for age, cohort and other covariates, the estimated period effect indicated declines in marijuana use in 1979–1992 and 2001–2006, and increases in 1992–2001 and 2006–2016. The period effect was positively and significantly associated with the proportion of people covered by Medical Marijuana Laws (MML) (correlation coefficients: 0.89 for total sample, 0.81 for males and 0.93 for females, all three p values < 0.01), but was not significantly associated with the Recreational Marijuana Laws (RML). The estimated cohort effect showed a historical decline in marijuana use in those who were born in 1954–1972, a sudden increase in 1972–1984, followed by a decline in 1984–2003.

The model derived trends in marijuana use were coincident with the laws and regulations on marijuana and other drugs in the United States since the 1950s. With more states legalizing marijuana use in the United States, emphasizing responsible use would be essential to protect youth from using marijuana.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Marijuana use and laws in the united states.

Marijuana is one of the most commonly used drugs in the United States (US) [ 1 ]. In 2015, 8.3% of the US population aged 12 years and older used marijuana in the past month; 16.4% of adolescents aged 12–17 years used in lifetime and 7.0% used in the past month [ 2 ]. The effects of marijuana on a person’s health are mixed. Despite potential benefits (e.g., relieve pain) [ 3 ], using marijuana is associated with a number of adverse effects, particularly among adolescents. Typical adverse effects include impaired short-term memory, cognitive impairment, diminished life satisfaction, and increased risk of using other substances [ 4 ].

Since 1937 when the Marijuana Tax Act was issued, a series of federal laws have been subsequently enacted to regulate marijuana use, including the Boggs Act (1952), Narcotics Control Act (1956), Controlled Substance Act (1970), and Anti-Drug Abuse Act (1986) [ 5 , 6 ]. These laws regulated the sale, possession, use, and cultivation of marijuana [ 6 ]. For example, the Boggs Act increased the punishment of marijuana possession, and the Controlled Substance Act categorized the marijuana into the Schedule I Drugs which have a high potential for abuse, no medical use, and not safe to use without medical supervision [ 5 , 6 ]. These federal laws may have contributed to changes in the historical trend of marijuana use among youth.

Movements to decriminalize and legalize marijuana use

Starting in the late 1960s, marijuana decriminalization became a movement, advocating reformation of federal laws regulating marijuana [ 7 ]. As a result, 11 US states had taken measures to decriminalize marijuana use by reducing the penalty of possession of small amount of marijuana [ 7 ].

The legalization of marijuana started in 1993 when Surgeon General Elder proposed to study marijuana legalization [ 8 ]. California was the first state that passed Medical Marijuana Laws (MML) in 1996 [ 9 ]. After California, more and more states established laws permitting marijuana use for medical and/or recreational purposes. To date, 33 states and the District of Columbia have established MML, including 11 states with recreational marijuana laws (RML) [ 9 ]. Compared with the legalization of marijuana use in the European countries which were more divided that many of them have medical marijuana registered as a treatment option with few having legalized recreational use [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ], the legalization of marijuana in the US were more mixed with 11 states legalized medical and recreational use consecutively, such as California, Nevada, Washington, etc. These state laws may alter people’s attitudes and behaviors, finally may lead to the increased risk of marijuana use, particularly among young people [ 13 ]. Reported studies indicate that state marijuana laws were associated with increases in acceptance of and accessibility to marijuana, declines in perceived harm, and formation of new norms supporting marijuana use [ 14 ].

Marijuana harm to adolescents and young adults

Adolescents and young adults constitute a large proportion of the US population. Data from the US Census Bureau indicate that approximately 60 million of the US population are in the 12–25 years age range [ 15 ]. These people are vulnerable to drugs, including marijuana [ 16 ]. Marijuana is more prevalent among people in this age range than in other ages [ 17 ]. One well-known factor for explaining the marijuana use among people in this age range is the theory of imbalanced cognitive and physical development [ 4 ]. The delayed brain development of youth reduces their capability to cognitively process social, emotional and incentive events against risk behaviors, such as marijuana use [ 18 ]. Understanding the impact of marijuana laws on marijuana use among this population with a historical perspective is of great legal, social and public health significance.

Inconsistent results regarding the impact of marijuana laws on marijuana use

A number of studies have examined the impact of marijuana laws on marijuana use across the world, but reported inconsistent results [ 13 ]. Some studies reported no association between marijuana laws and marijuana use [ 14 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ], some reported a protective effect of the laws against marijuana use [ 24 , 26 ], some reported mixed effects [ 27 , 28 ], while some others reported a risk effect that marijuana laws increased marijuana use [ 29 , 30 ]. Despite much information, our review of these reported studies revealed several limitations. First of all, these studies often targeted a short time span, ignoring the long period trend before marijuana legalization. Despite the fact that marijuana laws enact in a specific year, the process of legalization often lasts for several years. Individuals may have already changed their attitudes and behaviors before the year when the law is enacted. Therefore, it may not be valid when comparing marijuana use before and after the year at a single time point when the law is enacted and ignoring the secular historical trend [ 19 , 30 , 31 ]. Second, many studies adapted the difference-in-difference analytical approach designated for analyzing randomized controlled trials. No US state is randomized to legalize the marijuana laws, and no state can be established as controls. Thus, the impact of laws cannot be efficiently detected using this approach. Third, since marijuana legalization is a public process, and the information of marijuana legalization in one state can be easily spread to states without the marijuana laws. The information diffusion cannot be ruled out, reducing the validity of the non-marijuana law states as the controls to compare the between-state differences [ 31 ].

Alternatively, evidence derived based on a historical perspective may provide new information regarding the impact of laws and regulations on marijuana use, including state marijuana laws in the past two decades. Marijuana users may stop using to comply with the laws/regulations, while non-marijuana users may start to use if marijuana is legal. Data from several studies with national data since 1996 demonstrate that attitudes, beliefs, perceptions, and use of marijuana among people in the US were associated with state marijuana laws [ 29 , 32 ].

Age-period-cohort modeling: looking into the past with recent data

To investigate historical trends over a long period, including the time period with no data, we can use the classic age-period-cohort modeling (APC) approach. The APC model can successfully discompose the rate or prevalence of marijuana use into independent age, period and cohort effects [ 33 , 34 ]. Age effect refers to the risk associated with the aging process, including the biological and social accumulation process. Period effect is risk associated with the external environmental events in specific years that exert effect on all age groups, representing the unbiased historical trend of marijuana use which controlling for the influences from age and birth cohort. Cohort effect refers to the risk associated with the specific year of birth. A typical example is that people born in 2011 in Fukushima, Japan may have greater risk of cancer due to the nuclear disaster [ 35 ], so a person aged 80 in 2091 contains the information of cancer risk in 2011 when he/she was born. Similarly, a participant aged 25 in 1979 contains information on the risk of marijuana use 25 years ago in 1954 when that person was born. With this method, we can describe historical trends of marijuana use using information stored by participants in older ages [ 33 ]. The estimated period and cohort effects can be used to present the unbiased historical trend of specific topics, including marijuana use [ 34 , 36 , 37 , 38 ]. Furthermore, the newly established hierarchical APC (HAPC) modeling is capable of analyzing individual-level data to provide more precise measures of historical trends [ 33 ]. The HAPC model has been used in various fields, including social and behavioral science, and public health [ 39 , 40 ].

Several studies have investigated marijuana use with APC modeling method [ 17 , 41 , 42 ]. However, these studies covered only a small portion of the decades with state marijuana legalization [ 17 , 42 ]. For example, the study conducted by Miech and colleagues only covered periods from 1985 to 2009 [ 17 ]. Among these studies, one focused on a longer state marijuana legalization period, but did not provide detailed information regarding the impact of marijuana laws because the survey was every 5 years and researchers used a large 5-year age group which leads to a wide 10-year birth cohort. The averaging of the cohort effects in 10 years could reduce the capability of detecting sensitive changes of marijuana use corresponding to the historical events [ 41 ].

Purpose of the study

In this study, we examined the historical trends in marijuana use among youth using HAPC modeling to obtain the period and cohort effects. These two effects provide unbiased and independent information to characterize historical trends in marijuana use after controlling for age and other covariates. We conceptually linked the model-derived time trends to both federal and state laws/regulations regarding marijuana and other drug use in 1954–2016. The ultimate goal is to provide evidence informing federal and state legislation and public health decision-making to promote responsible marijuana use and to protect young people from marijuana use-related adverse consequences.

Materials and methods

Data sources and study population.

Data were derived from 31 waves of National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 1979–2016. NSDUH is a multi-year cross-sectional survey program sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The survey was conducted every 3 years before 1990, and annually thereafter. The aim is to provide data on the use of tobacco, alcohol, illicit drug and mental health among the US population.

Survey participants were noninstitutionalized US civilians 12 years of age and older. Participants were recruited by NSDUH using a multi-stage clustered random sampling method. Several changes were made to the NSDUH after its establishment [ 43 ]. First, the name of the survey was changed from the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA) to NSDUH in 2002. Second, starting in 2002, adolescent participants receive $30 as incentives to improve the response rate. Third, survey mode was changed from personal interviews with self-enumerated answer sheets (before 1999) to the computer-assisted person interviews (CAPI) and audio computer-assisted self-interviews (ACASI) (since 1999). These changes may confound the historical trends [ 43 ], thus we used two dummy variables as covariates, one for the survey mode change in 1999 and another for the survey method change in 2002 to control for potential confounding effect.

Data acquisition

Data were downloaded from the designated website ( https://nsduhweb.rti.org/respweb/homepage.cfm ). A database was used to store and merge the data by year for analysis. Among all participants, data for those aged 12–25 years ( n = 749,152) were included. We excluded participants aged 26 and older because the public data did not provide information on single or two-year age that was needed for HAPC modeling (details see statistical analysis section). We obtained approval from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida to conduct this study.

Variables and measurements

Current marijuana use: the dependent variable. Participants were defined as current marijuana users if they reported marijuana use within the past 30 days. We used the variable harmonization method to create a comparable measure across 31-wave NSDUH data [ 44 ]. Slightly different questions were used in NSDUH. In 1979–1993, participants were asked: “When was the most recent time that you used marijuana or hash?” Starting in 1994, the question was changed to “How long has it been since you last used marijuana or hashish?” To harmonize the marijuana use variable, participants were coded as current marijuana users if their response to the question indicated the last time to use marijuana was within past 30 days.

Chronological age, time period and birth cohort were the predictors. (1) Chronological age in years was measured with participants’ age at the survey. APC modeling requires the same age measure for all participants [ 33 ]. Since no data by single-year age were available for participants older than 21, we grouped all participants into two-year age groups. A total of 7 age groups, 12–13, ..., 24–25 were used. (2) Time period was measured with the year when the survey was conducted, including 1979, 1982, 1985, 1988, 1990, 1991... 2016. (3). Birth cohort was the year of birth, and it was measured by subtracting age from the survey year.

The proportion of people covered by MML: This variable was created by dividing the population in all states with MML over the total US population. The proportion was computed by year from 1996 when California first passed the MML to 2016 when a total of 29 states legalized medical marijuana use. The estimated proportion ranged from 12% in 1996 to 61% in 2016. The proportion of people covered by RML: This variable was derived by dividing the population in all states with RML with the total US population. The estimated proportion ranged from 4% in 2012 to 21% in 2016. These two variables were used to quantitatively assess the relationships between marijuana laws and changes in the risk of marijuana use.

Covariates: Demographic variables gender (male/female) and race/ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic and others) were used to describe the study sample.

Statistical analysis

We estimated the prevalence of current marijuana use by year using the survey estimation method, considering the complex multi-stage cluster random sampling design and unequal probability. A prevalence rate is not a simple indicator, but consisting of the impact of chronological age, time period and birth cohort, named as age, period and cohort effects, respectively. Thus, it is biased if a prevalence rate is directly used to depict the historical trend. HAPC modeling is an epidemiological method capable of decomposing prevalence rate into mutually independent age, period and cohort effects with individual-level data, while the estimated period and cohort effects provide an unbiased measure of historical trend controlling for the effects of age and other covariates. In this study, we analyzed the data using the two-level HAPC cross-classified random-effects model (CCREM) [ 36 ]:

Where M ijk represents the rate of marijuana use for participants in age group i (12–13, 14,15...), period j (1979, 1982,...) and birth cohort k (1954–55, 1956–57...); parameter α i (age effect) was modeled as the fixed effect; and parameters β j (period effect) and γ k (cohort effect) were modeled as random effects; and β m was used to control m covariates, including the two dummy variables assessing changes made to the NSDUH in 1999 and 2002, respectively.

The HAPC modeling analysis was executed using the PROC GLIMMIX. Sample weights were included to obtain results representing the total US population aged 12–25. A ridge-stabilized Newton-Raphson algorithm was used for parameter estimation. Modeling analysis was conducted for the overall sample, stratified by gender. The estimated age effect α i , period β j and cohort γ k (i.e., the log-linear regression coefficients) were directly plotted to visualize the pattern of change.

To gain insight into the relationship between legal events and regulations at the national level, we listed these events/regulations along with the estimated time trends in the risk of marijuana from HAPC modeling. To provide a quantitative measure, we associated the estimated period effect with the proportions of US population living with MML and RML using Pearson correlation. All statistical analyses for this study were conducted using the software SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Sample characteristics

Data for a total of 749,152 participants (12–25 years old) from all 31-wave NSDUH covering a 38-year period were analyzed. Among the total sample (Table 1 ), 48.96% were male and 58.78% were White, 14.84% Black, and 18.40% Hispanic.

Prevalence rate of current marijuana use

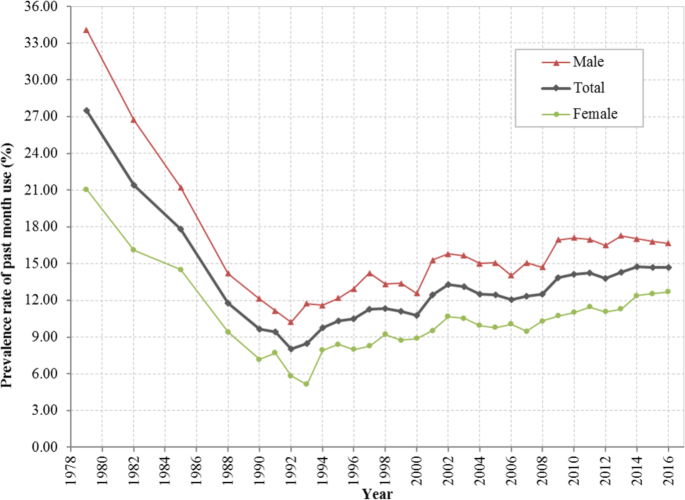

As shown in Fig. 1 , the estimated prevalence rates of current marijuana use from 1979 to 2016 show a “V” shaped pattern. The rate was 27.57% in 1979, it declined to 8.02% in 1992, followed by a gradual increase to 14.70% by 2016. The pattern was the same for both male and female with males more likely to use than females during the whole period.

Prevalence rate (%) of current marijuana use among US residents 12 to 25 years of age during 1979–2016, overall and stratified by gender. Derived from data from the 1979–2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)

HAPC modeling and results

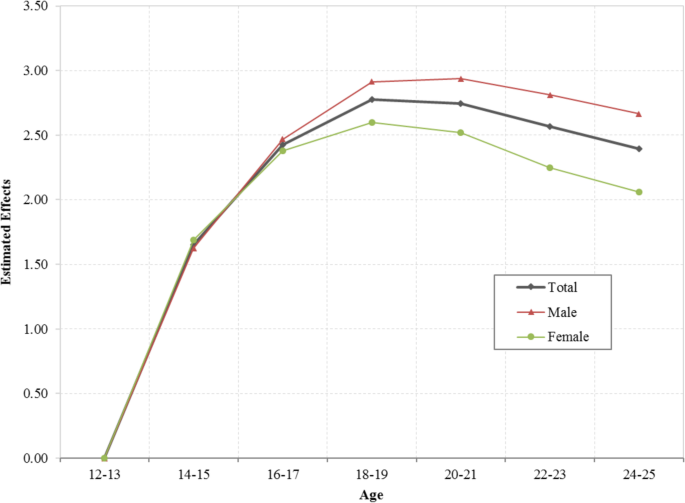

Estimated age effects α i from the CCREM [ 1 ] for current marijuana use are presented in Fig. 2 . The risk by age shows a 2-phase pattern –a rapid increase phase from ages 12 to 19, followed by a gradually declining phase. The pattern was persistent for the overall sample and for both male and female subsamples.

Age effect for the risk of current marijuana use, overall and stratified by male and female, estimated with hierarchical age-period-cohort modeling method with 31 waves of NSDUH data during 1979–2016. Age effect α i were log-linear regression coefficients estimated using CCREM (1), see text for more details

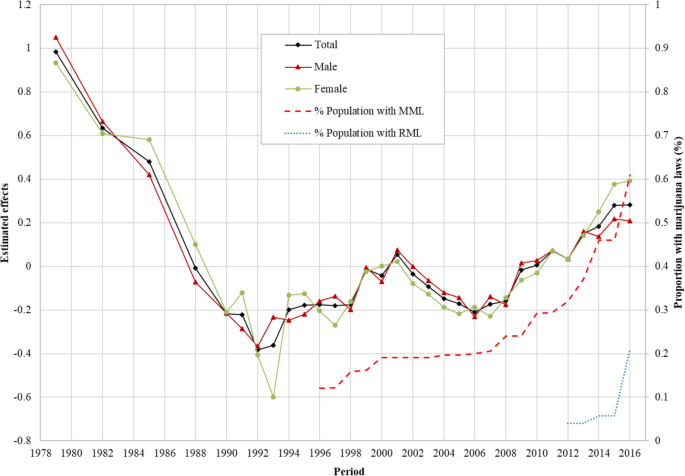

The estimated period effects β j from the CCREM [ 1 ] are presented in Fig. 3 . The period effect reflects the risk of current marijuana use due to significant events occurring over the period, particularly federal and state laws and regulations. After controlling for the impacts of age, cohort and other covariates, the estimated period effect indicates that the risk of current marijuana use had two declining trends (1979–1992 and 2001–2006), and two increasing trends (1992–2001 and 2006–2016). Epidemiologically, the time trends characterized by the estimated period effects in Fig. 3 are more valid than the prevalence rates presented in Fig. 1 because the former was adjusted for confounders while the later was not.

Period effect for the risk of marijuana use for US adolescents and young adults, overall and by male/female estimated with hierarchical age-period-cohort modeling method and its correlation with the proportion of US population covered by Medical Marijuana Laws and Recreational Marijuana Laws. Period effect β j were log-linear regression coefficients estimated using CCREM (1), see text for more details

Correlation of the period effect with proportions of the population covered by marijuana laws: The Pearson correlation coefficient of the period effect with the proportions of US population covered by MML during 1996–2016 was 0.89 for the total sample, 0.81 for male and 0.93 for female, respectively ( p < 0.01 for all). The correlation between period effect and proportion of US population covered by RML was 0.64 for the total sample, 0.59 for male and 0.49 for female ( p > 0.05 for all).

Likewise, the estimated cohort effects γ k from the CCREM [ 1 ] are presented in Fig. 4 . The cohort effect reflects changes in the risk of current marijuana use over the period indicated by the year of birth of the survey participants after the impacts of age, period and other covariates are adjusted. Results in the figure show three distinctive cohorts with different risk patterns of current marijuana use during 1954–2003: (1) the Historical Declining Cohort (HDC): those born in 1954–1972, and characterized by a gradual and linear declining trend with some fluctuations; (2) the Sudden Increase Cohort (SIC): those born from 1972 to 1984, characterized with a rapid almost linear increasing trend; and (3) the Contemporary Declining Cohort (CDC): those born during 1984 and 2003, and characterized with a progressive declining over time. The detailed results of HAPC modeling analysis were also shown in Additional file 1 : Table S1.

Cohort effect for the risk of marijuana use among US adolescents and young adults born during 1954–2003, overall and by male/female, estimated with hierarchical age-period-cohort modeling method. Cohort effect γ k were log-linear regression coefficients estimated using CCREM (1), see text for more details

This study provides new data regarding the risk of marijuana use in youth in the US during 1954–2016. This is a period in the US history with substantial increases and declines in drug use, including marijuana; accompanied with many ups and downs in legal actions against drug use since the 1970s and progressive marijuana legalization at the state level from the later 1990s till today (see Additional file 1 : Table S2). Findings of the study indicate four-phase period effect and three-phase cohort effect, corresponding to various historical events of marijuana laws, regulations and social movements.

Coincident relationship between the period effect and legal drug control

The period effect derived from the HAPC model provides a net effect of the impact of time on marijuana use after the impact of age and birth cohort were adjusted. Findings in this study indicate that there was a progressive decline in the period effect during 1979 and 1992. This trend was corresponding to a period with the strongest legal actions at the national level, the War on Drugs by President Nixon (1969–1974) President Reagan (1981–1989) [ 45 ], and President Bush (1989) [ 45 ],and the Anti-Drug Abuse Act (1986) [ 5 ].

The estimated period effect shows an increasing trend in 1992–2001. During this period, President Clinton advocated for the use of treatment to replace incarceration (1992) [ 45 ], Surgeon General Elders proposed to study marijuana legalization (1993–1994) [ 8 ], President Clinton’s position of the need to re-examine the entire policy against people who use drugs, and decriminalization of marijuana (2000) [ 45 ] and the passage of MML in eight US states.

The estimated period effect shows a declining trend in 2001–2006. Important laws/regulations include the Student Drug Testing Program promoted by President Bush, and the broadened the public schools’ authority to test illegal drugs among students given by the US Supreme Court (2002) [ 46 ].

The estimated period effect increases in 2006–2016. This is the period when the proportion of the population covered by MML progressively increased. This relation was further proved by a positive correlation between the estimated period effect and the proportion of the population covered by MML. In addition, several other events occurred. For example, over 500 economists wrote an open letter to President Bush, Congress and Governors of the US and called for marijuana legalization (2005) [ 47 ], and President Obama ended the federal interference with the state MML, treated marijuana as public health issues, and avoided using the term of “War on Drugs” [ 45 ]. The study also indicates that the proportion of population covered by RML was positively associated with the period effect although not significant which may be due to the limited number of data points of RML. Future studies may follow up to investigate the relationship between RML and rate of marijuana use.

Coincident relationship between the cohort effect and legal drug control

Cohort effect is the risk of marijuana use associated with the specific year of birth. People born in different years are exposed to different laws, regulations in the past, therefore, the risk of marijuana use for people may differ when they enter adolescence and adulthood. Findings in this study indicate three distinctive cohorts: HDC (1954–1972), SIC (1972–1984) and CDC (1984–2003). During HDC, the overall level of marijuana use was declining. Various laws/regulations of drug use in general and marijuana in particular may explain the declining trend. First, multiple laws passed to regulate the marijuana and other substance use before and during this period remained in effect, for example, the Marijuana Tax Act (1937), the Boggs Act (1952), the Narcotics Control Act (1956) and the Controlled Substance Act (1970). Secondly, the formation of government departments focusing on drug use prevention and control may contribute to the cohort effect, such as the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (1968) [ 48 ]. People born during this period may be exposed to the macro environment with laws and regulations against marijuana, thus, they may be less likely to use marijuana.

Compared to people born before 1972, the cohort effect for participants born during 1972 and 1984 was in coincidence with the increased risk of using marijuana shown as SIC. This trend was accompanied by the state and federal movements for marijuana use, which may alter the social environment and public attitudes and beliefs from prohibitive to acceptive. For example, seven states passed laws to decriminalize the marijuana use and reduced the penalty for personal possession of small amount of marijuana in 1976 [ 7 ]. Four more states joined the movement in two subsequent years [ 7 ]. People born during this period may have experienced tolerated environment of marijuana, and they may become more acceptable of marijuana use, increasing their likelihood of using marijuana.

A declining cohort CDC appeared immediately after 1984 and extended to 2003. This declining cohort effect was corresponding to a number of laws, regulations and movements prohibiting drug use. Typical examples included the War on Drugs initiated by President Nixon (1980s), the expansion of the drug war by President Reagan (1980s), the highly-publicized anti-drug campaign “Just Say No” by First Lady Nancy Reagan (early 1980s) [ 45 ], and the Zero Tolerance Policies in mid-to-late 1980s [ 45 ], the Anti-Drug Abuse Act (1986) [ 5 ], the nationally televised speech of War on Drugs declared by President Bush in 1989 and the escalated War on Drugs by President Clinton (1993–2001) [ 45 ]. Meanwhile many activities of the federal government and social groups may also influence the social environment of using marijuana. For example, the Federal government opposed to legalize the cultivation of industrial hemp, and Federal agents shut down marijuana sales club in San Francisco in 1998 [ 48 ]. Individuals born in these years grew up in an environment against marijuana use which may decrease their likelihood of using marijuana when they enter adolescence and young adulthood.

This study applied the age-period-cohort model to investigate the independent age, period and cohort effects, and indicated that the model derived trends in marijuana use among adolescents and young adults were coincident with the laws and regulations on marijuana use in the United States since the 1950s. With more states legalizing marijuana use in the United States, emphasizing responsible use would be essential to protect youth from using marijuana.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, study data were collected through a household survey, which is subject to underreporting. Second, no causal relationship can be warranted using cross-sectional data, and further studies are needed to verify the association between the specific laws/regulation and the risk of marijuana use. Third, data were available to measure single-year age up to age 21 and two-year age group up to 25, preventing researchers from examining the risk of marijuana use for participants in other ages. Lastly, data derived from NSDUH were nation-wide, and future studies are needed to analyze state-level data and investigate the between-state differences. Although a systematic review of all laws and regulations related to marijuana and other drugs is beyond the scope of this study, findings from our study provide new data from a historical perspective much needed for the current trend in marijuana legalization across the nation to get the benefit from marijuana while to protect vulnerable children and youth in the US. It provides an opportunity for stack-holders to make public decisions by reviewing the findings of this analysis together with the laws and regulations at the federal and state levels over a long period since the 1950s.

Availability of data and materials

The data of the study are available from the designated repository ( https://nsduhweb.rti.org/respweb/homepage.cfm ).

Abbreviations

Audio computer-assisted self-interviews

Age-period-cohort modeling

Computer-assisted person interviews

Cross-classified random-effects model

Contemporary Declining Cohort

Hierarchical age-period-cohort

Historical Declining Cohort

Medical Marijuana Laws

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse

National Survey on Drug Use and Health

Recreational Marijuana Laws

Sudden Increase Cohort

The United States

CDC. Marijuana and Public Health. 2017. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/marijuana/index.htm . Accessed 13 June 2018.

SAMHSA. Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. 2016 [cited 2018 Jan 31]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.htm

Committee on the Health Effects of Marijuana: An Evidence Review and Research Agenda, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, Health and Medicine Division, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: the current state of evidence and recommendations for research. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2017.

Collins C. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(9):879.

PubMed Google Scholar

Belenko SR. Drugs and drug policy in America: a documentary history. Westport: Greenwood Press; 2000.

Google Scholar

Gerber RJ. Legalizing marijuana: Drug policy reform and prohibition politics. Westport: Praeger; 2004.

Single EW. The impact of marijuana decriminalization: an update. J Public Health Policy. 1989:456–66.

Article CAS Google Scholar

SFChronicle. Ex-surgeon general backed legalizing marijuana before it was cool [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2018 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.sfchronicle.com/business/article/Ex-surgeon-general-backed-legalizing-marijuana-6799348.php

PROCON. 31 Legal Medical Marijuana States and DC. 2018 [cited 2018 Oct 4]. Available from: https://medicalmarijuana.procon.org/view.resource.php?resourceID=000881

Bifulco M, Pisanti S. Medicinal use of cannabis in Europe: the fact that more countries legalize the medicinal use of cannabis should not become an argument for unfettered and uncontrolled use. EMBO Rep. 2015;16(2):130–2.

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Models for the legal supply of cannabis: recent developments (Perspectives on drugs). 2016. Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/pods/legal-supply-of-cannabis . Accessed 10 Jan 2020.

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Cannabis policy: status and recent developments. 2017. Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/topics/cannabis-policy_en#section2 . Accessed 10 Jan 2020.

Hughes B, Matias J, Griffiths P. Inconsistencies in the assumptions linking punitive sanctions and use of cannabis and new psychoactive substances in Europe. Addiction. 2018;113(12):2155–7.

Article Google Scholar

Anderson DM, Hansen B, Rees DI. Medical marijuana laws and teen marijuana use. Am Law Econ Rev. 2015;17(2):495-28.

United States Census Bureau. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Single Year of Age and Sex for the United States, States, and Puerto Rico Commonwealth: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2016 2016 Population Estimates. 2017 [cited 2018 Mar 14]. Available from: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk

Chen X, Yu B, Lasopa S, Cottler LB. Current patterns of marijuana use initiation by age among US adolescents and emerging adults: implications for intervention. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43(3):261–70.

Miech R, Koester S. Trends in U.S., past-year marijuana use from 1985 to 2009: an age-period-cohort analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;124(3):259–67.

Steinberg L. The influence of neuroscience on US supreme court decisions about adolescents’ criminal culpability. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(7):513–8.

Sarvet AL, Wall MM, Fink DS, Greene E, Le A, Boustead AE, et al. Medical marijuana laws and adolescent marijuana use in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2018;113(6):1003–16.

Hasin DS, Wall M, Keyes KM, Cerdá M, Schulenberg J, O’Malley PM, et al. Medical marijuana laws and adolescent marijuana use in the USA from 1991 to 2014: results from annual, repeated cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(7):601–8.

Pacula RL, Chriqui JF, King J. Marijuana decriminalization: what does it mean in the United States? National Bureau of Economic Research; 2003.

Donnelly N, Hall W, Christie P. The effects of the Cannabis expiation notice system on the prevalence of cannabis use in South Australia: evidence from the National Drug Strategy Household Surveys 1985-95. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2000;19(3):265–9.

Gorman DM, Huber JC. Do medical cannabis laws encourage cannabis use? Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18(3):160–7.

Lynne-Landsman SD, Livingston MD, Wagenaar AC. Effects of state medical marijuana laws on adolescent marijuana use. Am J Public Health. 2013 Aug;103(8):1500–6.

Pacula RL, Powell D, Heaton P, Sevigny EL. Assessing the effects of medical marijuana laws on marijuana and alcohol use: the devil is in the details. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2013.

Harper S, Strumpf EC, Kaufman JS. Do medical marijuana laws increase marijuana use? Replication study and extension. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22(3):207–12.

Stolzenberg L, D’Alessio SJ, Dariano D. The effect of medical cannabis laws on juvenile cannabis use. Int J Drug Policy. 2016;27:82–8.

Wang GS, Roosevelt G, Heard K. Pediatric marijuana exposures in a medical marijuana state. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(7):630–3.

Wall MM, Poh E, Cerdá M, Keyes KM, Galea S, Hasin DS. Adolescent marijuana use from 2002 to 2008: higher in states with medical marijuana laws, cause still unclear. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21(9):714–6.

Chen X, Yu B, Stanton B, Cook RL, Chen D-GD, Okafor C. Medical marijuana laws and marijuana use among U.S. adolescents: evidence from michigan youth risk behavior surveillance data. J Drug Educ. 2018;47237918803361.

Chen X. Information diffusion in the evaluation of medical marijuana laws’ impact on risk perception and use. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(12):e8.

Chen X, Yu B, Stanton B, Cook RL, Chen DG, Okafor C. Medical marijuana laws and marijuana use among US adolescents: Evidence from Michigan youth risk behavior surveillance data. J Drug Educ. 2018;48(1-2):18-35.

Yang Y, Land K. Age-Period-Cohort Analysis: New Models, Methods, and Empirical Applications. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2013.

Yu B, Chen X. Age and birth cohort-adjusted rates of suicide mortality among US male and female youths aged 10 to 19 years from 1999 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9):e1911383.

Akiba S. Epidemiological studies of Fukushima residents exposed to ionising radiation from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant prefecture--a preliminary review of current plans. J Radiol Prot. 2012;32(1):1–10.

Yang Y, Land KC. Age-period-cohort analysis of repeated cross-section surveys: fixed or random effects? Sociol Methods Res. 2008;36(3):297–326.

O’Brien R. Age-period-cohort models: approaches and analyses with aggregate data. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2014.

Book Google Scholar

Chen X, Sun Y, Li Z, Yu B, Gao G, Wang P. Historical trends in suicide risk for the residents of mainland China: APC modeling of the archived national suicide mortality rates during 1987-2012. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;54(1):99–110.

Yang Y. Social inequalities in happiness in the United States, 1972 to 2004: an age-period-cohort analysis. Am Sociol Rev. 2008;73(2):204–26.

Reither EN, Hauser RM, Yang Y. Do birth cohorts matter? Age-period-cohort analyses of the obesity epidemic in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(10):1439–48.

Kerr WC, Lui C, Ye Y. Trends and age, period and cohort effects for marijuana use prevalence in the 1984-2015 US National Alcohol Surveys. Addiction. 2018;113(3):473–81.

Johnson RA, Gerstein DR. Age, period, and cohort effects in marijuana and alcohol incidence: United States females and males, 1961-1990. Substance Use Misuse. 2000;35(6–8):925–48.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 NSDUH: Summary of National Findings, SAMHSA, CBHSQ. 2014 [cited 2018 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.htm

Bauer DJ, Hussong AM. Psychometric approaches for developing commensurate measures across independent studies: traditional and new models. Psychol Methods. 2009;14(2):101–25.

Drug Policy Alliance. A Brief History of the Drug War. 2018 [cited 2018 Sep 27]. Available from: http://www.drugpolicy.org/issues/brief-history-drug-war

NIDA. Drug testing in schools. 2017 [cited 2018 Sep 27]. Available from: https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/drug-testing/faq-drug-testing-in-schools

Wikipedia contributors. Legal history of cannabis in the United States. 2015. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Legal_history_of_cannabis_in_the_United_States&oldid=674767854 . Accessed 24 Oct 2017.

NORML. Marijuana law reform timeline. 2015. Available from: http://norml.org/shop/item/marijuana-law-reform-timeline . Accessed 24 Oct 2017.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Epidemiology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, 32608, USA

Bin Yu & Xinguang Chen

Department of Epidemiology and Health Statistics School of Health Sciences, Wuhan University, Wuhan, 430071, China

Xiangfan Chen & Hong Yan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

BY designed the study, collected the data, conducted the data analysis, drafted and reviewed the manuscript; XGC designed the study and reviewed the manuscript. XFC and HY reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hong Yan .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida. Data in the study were public available.

Consent for publication

All authors consented for the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: table s1..

Estimated Age, Period, Cohort Effects for the Trend of Marijuana Use in Past Month among Adolescents and Emerging Adults Aged 12 to 25 Years, NSDUH, 1979-2016. Table S2. Laws at the federal and state levels related to marijuana use.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Yu, B., Chen, X., Chen, X. et al. Marijuana legalization and historical trends in marijuana use among US residents aged 12–25: results from the 1979–2016 National Survey on drug use and health. BMC Public Health 20 , 156 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8253-4

Download citation

Received : 15 June 2019

Accepted : 21 January 2020

Published : 04 February 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8253-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Adolescents and young adults

- United States

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Journal of Cannabis Research

Aims and scope.

The Journal of Cannabis Research is an international, fully open access, peer-reviewed journal covering all topics pertaining to cannabis , including original research, perspectives, commentaries and protocols. Our goal is to provide an accessible outlet for expert interdisciplinary discourse on cannabis research.

Review of the current ongoing clinical trials exploring the possible anti-anxiety effects of cannabidiol

Authors: Rhenu Bhuller, Walter K. Schlage and Julia Hoeng

Association between cannabis use and physical activity in the United States based on legalization and health status

Authors: Ray M. Merrill, Kendyll Ashton-Hwang and Liliana Gallegos

Cannabis-related information sources among US residents: A probability-weighted nationally representative survey

Authors: Kevin F. Boehnke, Tristin Smith, Michael R. Elliott, Adrianne R. Wilson-Poe and Daniel J. Kruger

Attitudes toward driving after cannabis use: a systematic review

Authors: Bianca Boicu, Durr Al-Hakim, Yue Yuan and Jeffrey Brubacher

Changes in health-related quality of life over the first three months of medical marijuana use

Authors: Michelle R. Lent, Thomas R. McCalmont, Megan M. Short and Karen L. Dugosh

Most recent articles RSS

View all articles

Processing and extraction methods of medicinal cannabis: a narrative review

Authors: Masoumeh Pourseyed Lazarjani, Owen Young, Lidya Kebede and Ali Seyfoddin

Delta-8-THC: Delta-9-THC’s nicer younger sibling?

Authors: Jessica S. Kruger and Daniel J. Kruger

Cannabis consumption is associated with lower COVID-19 severity among hospitalized patients: a retrospective cohort analysis

Authors: Carolyn M. Shover, Peter Yan, Nicholas J. Jackson, Russell G. Buhr, Jennifer A. Fulcher, Donald P. Tashkin and Igor Barjaktarevic

Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV): a commentary on potential therapeutic benefit for the management of obesity and diabetes

Authors: Amos Abioye, Oladapo Ayodele, Aleksandra Marinkovic, Risha Patidar, Adeola Akinwekomi and Adekunle Sanyaolu

Total and differential white blood cell count in cannabis users: results from the cross-sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005–2016

Authors: Omayma Alshaarawy

Most accessed articles RSS

We are recruiting!

Journal of Cannabis Research is recruiting Associate Editors. As the growth of the journal continues, we are looking to expand our editorial team. If you have experience in any form of cannabis research, we would like to hear from you. Please follow the link below to find out more about the role and apply.

Webinar Series: Institute of Cannabis Research

Register for the Webinar Series hosted by the Institute of Cannabis Research and watch a comprehensive archive of cutting edge science presented by experts across the spectrum of cannabis research. The Cannabis Research Series hosted in collaboration with the Lambert Center at Thomas Jefferson University Cannabis Plant Science and Cultivation , hosted in collaboration with the Volcani Institute in Israel.

The Two Sides of Hemp

About the Institute

The Journal of Cannabis Research is the official publication of the Institute of Cannabis Research (ICR), which was established in June 2016 through an innovative partnership between Colorado State University Pueblo, the state of Colorado, and Pueblo County.

The ICR is the first US multi-disciplinary cannabis research center at a regional, comprehensive institution. The primary goal of the ICR is to conduct or fund research related to cannabis and publicly disseminate the results of the research, which it does so in partnership with the Journal. It also advises other Colorado-based higher education institutions on the development of a cannabis-related curriculum and supports the translation of discoveries into innovative applications that improve lives.

Find out more about the the Institute via the link below, as well as the Colorado state University–Pueblo website and Institute's research funding outcomes .

Affiliated with

An official publication of the Institute of Cannabis Research

- Editorial Board

- Instructions for Authors

- Instructions for Editors

- Sign up for article alerts and news from this journal

Annual Journal Metrics

Citation Impact 2023 Journal Impact Factor: 4.1 5-year Journal Impact Factor: 3.8 Source Normalized Impact per Paper (SNIP): 0.894 SCImago Journal Rank (SJR): 0.692

Speed 2023 Submission to first editorial decision (median days): 22 Submission to acceptance (median days): 211

Usage 2023 Downloads: 596,678 Altmetric mentions: 1,834

- More about our metrics

ISSN: 2522-5782

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Cannabis Unveiled: An Exploration of Marijuana’s History, Active Compounds, Effects, Benefits, and Risks on Human Health

Khaled m hasan.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Khaled M Hasan, Physician Assistant Department, School of Pharmacy and Health Professions, University of Maryland Eastern Shore, Hazel Hall, Suite 1042, Princess Anne, MD 21853, USA. Email: [email protected]

Received 2023 Mar 16; Accepted 2023 May 30; Collection date 2023.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages ( https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage ).

Marijuana, also known as cannabis, is a psychoactive drug that comes from the Cannabis plant. Marijuana can be smoked, vaporized, or consumed through edibles in a variety of ways. Perception changes, changes in mood, and problems with coordination are all possible side effects. Marijuana is used for both recreational and medical purposes to treat a variety of health conditions. The literature review on the effects of marijuana on the human body has increased in recent years as more states legalize its use. It is important to investigate the benefits and harmful effects of marijuana on individuals due to the widespread use of cannabis-derived substances like marijuana for medical, recreational, and combined purposes. The paper will review different aspects of marijuana in 4 main domains. A thorough discussion of marijuana’s definition, history, mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics, and effects on human cells will be given in the first domain. The second domain will concentrate on marijuana’s negative effects, while the third domain will look at marijuana’s possible positive impacts, such as its usage in controlling multiple sclerosis, treating obesity, lowering social anxiety, and managing pain. The fourth domain will concentrate on marijuana’s effects on anxiety, educational attainment, and social consequences. Additionally, this paper also will provide a highlight of the history of marijuana use and governmental legislation, both of which play a significant role in determining how the public views marijuana. In conclusion, this paper provides a comprehensive review of marijuana’s effects, which may be of interest to a large readership. This review adds to the continuing discussion about the use of marijuana by analyzing the data that is currently available about the possible advantages and disadvantages of marijuana usage.

Keywords: Marijuana, cannabis, benefits, harmful, human body, social impacts, education attainment, legislation

Introduction

Marijuana and cannabis are often used interchangeably, but they technically refer to different things. “Cannabis” is the scientific name for the plant species that includes both marijuana and hemp. “Marijuana” specifically refers to the strains of cannabis that contain high levels of the psychoactive compound delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which is responsible for the plant’s intoxicating effects. “Hemp” on the other hand is a strain of cannabis that contains very low levels of THC and is mostly used for industrial and medical purposes. 1

The use of marijuana for both recreational and medicinal purposes can be traced back 6000 years. 1 THC interacts with cannabidiol (CB) receptors present in various organs, including the heart, brain, peripheral nervous system, skeletal muscles, and myocytes. 2 Marijuana is a naturally occurring substance that contains various chemicals. It is derived from hemp, a plant mainly grown for fiber production, and is part of the Cannabis species that contains cannabinoids. 3 The World Health Organization reports that marijuana is the most commonly used drug worldwide, with a global prevalence of 2.5%. It is a popular drug that can be consumed through smoking or orally. Marijuana usage is notably prevalent in the United States, with more than 22 million individuals aged 12 years or above having used it at least once in their lives. 4

The purpose of this review article is to provide an overview of marijuana, differentiate between the terms, highlight their historical use and touch upon the historical use of marijuana and governmental legislation. It also aims to establish the presence of various active substances in marijuana, explain their mechanism of action, and discuss the pharmacokinetics of cannabis. Furthermore, this article intends to explore the effects of marijuana on human cells, both beneficial and harmful, as well as its impact on education attainment, cardiovascular disorders, addiction potential, mental health, and its relationship with cancer. Lastly, it aims to address the social impacts of marijuana.

The history of marijuana

In the United States, marijuana was commonly consumed for recreational purposes until 1941, and it was also medically prescribed to alleviate symptoms such as arthritis, nausea, and labor pains. 1 , 3 During the 1930s, marijuana was portrayed as a substance that induced violent behavior in people, while in the 1960s it became a symbol of counterculture and rebellion against societal norms. 1 In 1970, the Controlled Substance Act classified marijuana as a Schedule 1 drug. 3 Despite this, the use of marijuana for both recreational and medicinal purposes has risen in the United States. This is in part due to a survey showing that 81% of American adults believe it has at least 1 medical benefit. 5

For more than 4000 years, marijuana has been utilized both for medicinal and recreational objectives. Its earliest known medicinal usage was documented in a Chinese artifact from 2700 B.C., which suggests that cannabis was used to treat a range of conditions including malaria, poor memory, gout, and rheumatism. 1 After originating in China, marijuana spread to other regions including Korea, India, and East Africa. The cultivation of hemp, which has strong fibers, also contributed to its spread. 1 , 2 For example, the Spanish brought it to America in the mid-1500s for cultivation. 1

The history of marijuana use and governmental legislation

In the United States, cannabis legalization has been a contentious issue in recent years. Cannabis has been legalized for medical and/or recreational use in some states, but not in others. As of April 2021, 36 states and the District of Columbia had legalized medical cannabis, while 15 states and the District of Columbia had legalized recreational cannabis, as reported by the Congressional Research Service. 6

The legalization of cannabis has been significantly influenced by public opinion. A 2021 Seat Exploration Center overview saw that 91% of Americans support the utilization of clinical pot, while 60% help the sanctioning of sporting marijuana. 7

The potential for tax revenue is yet another factor that is driving the legalization of cannabis. Tax revenues have significantly increased in states that have legalized cannabis. For instance, the monthly state marijuana tax and fee revenue that is posted in the Colorado state accounting system is shown in the Marijuana Tax Reports. The state’s retail marijuana sales tax, which accounts for 15% of retail marijuana sales, and the state’s retail marijuana excise tax, which accounts for 15% of wholesale sales and transfers of retail marijuana, all contribute to the state’s tax revenue. Fees for marijuana licenses and applications generate revenue. 8

Concerns about racial disparities in drug policing and shifting attitudes toward drug use and addiction have also had an impact on the legalization of cannabis. In many states, “cannabis policy is shifting from a criminal justice perspective to a public health and safety approach,” as noted in a report by the National Conference of State Legislatures. 9

The prohibition of cannabis has historically been used to oppress racial groups, according to the Drug War Statistics. 10 For instance, cannabis was portrayed as a dangerous and addictive drug in the early 1900s and was associated with Mexican immigrants and African American jazz musicians. Despite similar rates of drug use, Black Americans are significantly more likely than White Americans to be arrested for drug offenses. This stigma continues to this day. 11 The article also mentions that the failure of the War on Drugs played a role in the legalization of cannabis. The Conflict on Medications, which started during the 1970s, was planned to lessen drug use and medication-related wrongdoing through forceful policing. Notwithstanding, pundits contend that the Conflict on Medications has been insufficient and has prompted the mass imprisonment of peaceful medication guilty parties. 10

Several states have passed laws making cannabis legal for medical and/or recreational use to address these issues. Age restrictions and licensing requirements for dispensaries are 2 examples of the kinds of regulations that are typically included in these laws to lessen the negative effects of drug use. 12 However, the legalization of cannabis faces numerous obstacles, which may include worries about an increase in drug-related use and addiction. 13

Despite these difficulties, the trend toward the legitimization of marijuana will continue in the near future. 14 The legal landscape pertaining to cannabis is likely to become increasingly complex as public opinion continues to shift in favor of legalization and as more states adopt policies that are favorable to the use of cannabis. 7 In general, the legitimization of marijuana is a complicated issue, with different social and political variables driving its sanctioning at the state level. 15 It will be crucial to take into account the various dangers and benefits of cannabis, as well as the potential impact of cannabis policy on public health and safety, as the debate over its legalization progresses. 16

Active substances of marijuana

More than 500 chemicals have been identified in cannabis. However, the most extensively studied are cannabinoids, which are chemicals with 21 carbon atoms. 17 The cannabinoids found in marijuana are referred to as Phytocannabinoids, which are naturally occurring chemicals. 17 The active chemicals are Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and cannabidiol (CBD). THC is the psychoactive ingredient, while CBD may also affect the brain and other organs in various ways. 2 , 17

Mechanism of action of marijuana

The human body has the endocannabinoid (eCB) system that plays a crucial role in the body by regulating functions such as sleep, eating, forgetting, relaxing, and protecting the body. The eCBs have a chemical structure that is similar to those of THC and CBD. 17 The common eCB is referred to as N -arachidonoylethanolamine or anandamide (AEA), which is located in the brain. 4 , 17 The second cannabinoid ligand found in the gastrointestinal tract is referred to as 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), which is located in the intestine. 4 After oral administration, THC and CBD will be hydrolyzed by the liver and then bind to the 2-AG receptors in the gastrointestinal tract. 17

The active Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) binds to the cannabinoid receptors in the brain cells, where it can interfere with various physical and mental functions. 4 , 17 The brain functions commonly affected by THC include memory, pleasure, balance, posture, and reaction time depending on the area of the brain. 5 These effects may be explained primarily by cannabinoids binding to the G- protein-coupled cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2. 17

The endocannabinoid system comprises the receptors CB1 and CB2, which respond to cannabinoids, the natural endogenous cannabinoids known as N -arachidonoylethanolamine (also called anandamide or AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), as well as their respective enzymes for degradation, which are fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) and monoacylglycerol lipase. 18

CB1 receptors are mainly found on presynaptic peripheral and central nerve terminals, with lower expression in various other peripheral organs. In contrast, CB2 receptors are predominantly concentrated in peripheral tissues and immune cells, where they regulate the release of cytokines and cell migration. However, CB2 receptors are also present in the nervous system, albeit to a lesser extent. 19

CB1 receptors are primarily located in the cortex, hippocampus, spinal cord, cerebellum, basal ganglia, and hypothalamus. 17 The hippocampus and the cortex are regions of the brain connected to learning and memory. As a result, THC binding to CB1 receptors can impede an individual’s ability to create new memories or shift focus. 5 Similarly, THC and CBD may interfere with the normal functioning of the cerebellum and basal ganglia, which are essential for maintaining balance, reaction time, coordination, and posture. 5

Phyto-cannabinoids also bind with transient receptor potential (TPR) channels that are responsible for the transmission of ions, which may interfere with the transmission of neural signals. 17 THC, which has a stronger affinity than CBD, also attaches to monoamine transporters such as serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine 17 triggering the release of dopamine results in higher than normal levels. 17 Elevated dopamine levels produce 2 main effects. Firstly, it activates the reward system which created a euphoric effect. Secondly, since the system governs behavior such as sex and eating, THC makes marijuana to be addictive as other drugs.

Marijuana’s ability to interact with various endocrine systems forms the foundation for its potential use as a treatment for various conditions. Studies have shown that certain nervous system disorders such as migraines, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, fibromyalgia, and irritable bowel syndrome may be caused by endocrine deficiencies due to genetic or physical factors. 17 Therefore, compounds like THC and CBD may be used to improve the management of these conditions as they have similar mechanisms to the cannabinoids found in the human body. However, the wide range of effects of marijuana suggests that it should only be used under medical supervision as it can have negative effects if abused.

Pharmacokinetic of cannabis

The way that THC, the psychoactive component of cannabis, is metabolized in the body depends on the method of consumption. 17 , 20 When taken orally, it is processed by the liver and converted into different metabolites, with the majority being eliminated in the feces and urine. 6

When consumed orally, THC is metabolized by the CYP450 enzyme system into 2 active metabolites: 11-OH-THC, which is psychoactive, and 11-COOH-THC, which is not. The majority of cannabis is eliminated from the body through feces as the 11-OH-THC metabolite (65%) and urine as the 11-COOH-THC metabolite (20%). 20 Research has shown that the amount of THC that can enter the bloodstream after being consumed orally is low, with a bioavailability of 4-12%. 17

Moreover, since THC is highly lipid-soluble, it is rapidly stored in fat tissues where it accumulates. 17 From these fat deposits, THC is slowly released back into the bloodstream. 17 On the other hand, if THC is inhaled its metabolites enter the bloodstream more quickly through the lung, and effects are felt within 6 to 10 minutes. 17 Furthermore, a study has shown that CYP2C9 polymorphisms can also lead to significant changes in THC bioavailability. 20 It has been found that CYP2C9 polymorphisms result in a reduction of CYP2C9 metabolic activity which leads to an increase in THC exposure 2- to 3-fold. This type of CYP2C9 polymorphism is highly prevalent up to 35% in white individuals compared with other racial groups. 20

Like THC, CBD, another chemical found in cannabis, enters the body and is metabolized into multiple metabolites, with the most prevalent being hydroxylated 7-COOH derivatives. 17 The pharmacokinetics of CBD compound is complex. When inhaled, its bioavailability is between 11% and 45%, but when taken orally it is around 6%. 20 Furthermore, like THC, CBD is highly lipid-soluble and distributes quickly into the brain, adipose tissues, and other organs. CBD can act as either an agonist or antagonist to their binding site. 17

Research indicates how THC and CBD interact with specific enzymes in the body especially cytochrome P450 isoenzymes, which can affect the metabolism of other drugs. 17 , 20 Some studies have shown that THC is a CYP1A2 inducer which leads to reduced drug concentration by increasing metabolism and consequently decreasing the drug effect. 17 , 20 On the other hand, CBD has been found to inhibit the activity of CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 enzymes, which can lead to an increase in drug concentration due to a reduction in metabolism, potentially leading to significant adverse effects. 17 , 20

The Effects of Marijuana on the Human Body

The effects on human cells.

THC and CBD also have a wide range of effects on human cells. The primary effects of THC on the cellular level include the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation which leads to alteration in lipid metabolism and triggers the release of inflammatory cytokines. 21

Inflammatory cytokines are classified into 2 categories: pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory. Pro-inflammatory cytokines cause inflammation and pain, while anti-inflammatory cytokines can decrease pain and reduce inflammation. It’s crucial to maintain a balance between the 2 types of cytokines. THC’s impact on this balance can lead to tissue damage, particularly in organs that are sensitive such as the lungs, liver, and kidneys. Furthermore, THC can cause oxidative stress by producing more reactive oxygen species (ROS) than the body’s antioxidant defense system can handle. 22 Oxidative stress results in the formation of free radicals, which are unstable radical molecules with unpaired electrons. Free radicals interact with biomolecules such as carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids, which can cause permanent changes.

Cannabinoids can also contribute to the development of atherogenesis in 2 main ways. Firstly, ROS, which is primarily caused by CB1 receptor agonists, can cause damage to endothelial cells. Additionally, CB2 receptor agonists can increase inflammation and decrease the expression of cell adhesion molecules. Furthermore, lipid metabolism may also be affected by the oxidation of low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL), which can increase the expression of CB1 and CB2 receptors and enhance the production of endogenous cannabinoids. 23 As a result, it causes the accumulation of lipids in macrophages, which are specialized cells present in the liver and lungs that help eliminate harmful organisms. 23 , 24 Thus, the active compounds in cannabis can harm different types of cells, particularly in the lungs, liver, kidney, and heart.

Harmful effects of marijuana

The growing legalization and acceptance of marijuana have led to an increase in its use in America for both medicinal and recreational purposes. 25 In 2016 and 2017, more than 39 million Americans reported having used marijuana in the past year. 23 Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the most psychoactive in marijuana.

Various organs of the human body contain cannabinoid (CB1 and CB2) receptors, including the brain, peripheral nervous system, liver, skeletal muscles, and myocytes. 23 Due to the location of the cannabinoid receptors on multiple organs, marijuana can have various harmful effects, including interfering with learning ability, mental disorders, addiction, cardiovascular disorders, and certain types of cancers.

Cardiovascular disorders

Marijuana may also increase the risk of individuals developing cardiovascular disorders. Approximately 2 million Americans who have been diagnosed with cardiovascular disorders reported using marijuana. 26 It has been found that smoking marijuana is associated with cardiotoxicity, similar to the effects of smoking cigarettes. 27 Research has shown that smoking marijuana has similar cardiovascular risks as smoking cigarettes. Despite smoking fewer puffs, users inhale deeper and hold the smoke longer, raising the risk of cardiotoxicity. Additionally, marijuana increases the risk of patients diagnosed with cardiovascular disorders such as atherosclerotic or developing coronary artery disease. 26

A study previously revealed that cannabis consumption can raise heart rate and blood pressure, thereby increasing the demand for oxygen in the heart. Furthermore, prolonged use of marijuana may cause oxidative stress that leads to cellular damage, platelet activation, induction of an inflammatory response, and the formation of oxidized low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (ox-LDL). THC may also cause a release of catecholamines and beta-adrenergic stimulation, increasing the likelihood of arrhythmias. People who smoke marijuana have a 3.3 times greater risk of experiencing a cerebrovascular event. 21 Marijuana increases the risk of thrombosis and ischemia, which may contribute to the development of peripheral artery disease. 27 Thus, marijuana use can lead to multiple cardiovascular disorders, particularly in individuals who already have these conditions.

The relationship with cancer

Research has been conducted on the potential use of marijuana and specific compounds found in the plant, such as THC and CBD, to alleviate symptoms associated with cancer and cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy. Some evidence suggests that certain cannabinoids may be effective in managing these side effects. 14 It is important to note that marijuana can have adverse effects and potential complications. Choosing to avoid or postpone conventional medical treatment for cancer or relying solely on marijuana to manage the symptoms of cancer, can lead to serious health risks. 28

Studies on the compounds in marijuana, known as cannabinoids, have indicated that certain cannabinoids may be useful in managing symptoms of nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy, as well as in treating neuropathic pain. 28 Marijuana use introduces cannabinoids, including THC, into the body, but it also includes harmful substances such as toxins and carcinogens found in tobacco smoke that can harm the lungs and cardiovascular system. 29 , 30 While more research is needed to determine the effects of marijuana on lung and other respiratory cancers, limited evidence suggests a connection between marijuana smoking and testicular cancer. 14 , 31

The concentration levels of active compounds in marijuana vary depending on the form in which it is consumed, which may explain the different effects on different individuals. Further research is necessary to fully comprehend the effects of marijuana use on cancer. 32

Another research suggests that using marijuana can increase the risk of developing certain types of cancer. For instance, a study conducted in New York Hospital found that individuals who use marijuana have a 2.6 times higher risk of upper aerodigestive tract cancer. Similarly, there is significant evidence linking marijuana use to Human papillomavirus-16 (HPV-16) positive head and neck cancer. 33 Additionally, some studies have indicated that marijuana use can increase the risk of developing lung cancer by 8.2 times. However, it is worth noting that heavy cannabis use for over 10 joint years primarily puts adults aged 55 years and older at a higher risk of developing lung cancer. 34

Marijuana use for over 10 years has been associated with a 1.5 times higher risk of testicular cancer. Additionally, paternal marijuana use has been linked to an increased risk of myeloid leukemia in their children, and maternal marijuana use during the first trimester may increase the risk of neuroblastoma in the child by 4 times. 33

The effects of cannabis on cancer risk vary depending on the type of cancer, the affected organ, and the receptors that are stimulated. 35 This is due to changes in the representation of CB1 and CB2 receptors observed in various types of cancers. 35 , 36 For instance, in Hodgkin lymphoma and cellular hepatocarcinoma, the expression of CB1 receptors is increased. 35 Conversely, ovarian cancers are associated with increased severity when CB2 receptors are expressed. Additionally, there is a high correlation between the overexpression of CB2 receptors and human breast adenocarcinoma and glioma, both of which are linked to breast cancer and malignant brain tumors. 35

In addition, research has linked variations in CB1 and CB2 receptors to poor outcomes following surgery for stage IV colorectal cancer. 35 THC is the primary compound that has been linked to an increased risk of cancer development, and the specific tissue where CB1 and CB2 receptors are disrupted determines the likelihood of cellular abnormalities and changes in enzymes and neurotransmitters. 36 Dysregulation of the endocannabinoid system occurs when there is an overproduction or underproduction of CB1 and CB2 receptors, which can lead to several health problems, including cancer. 36 For instance, up-regulation of CB1 receptors without changes in the regulation of CB2 is associated with an increase in the risk of pancreatic cancer. Conversely, inhibiting CB1 receptors in the colon tissue may increase the risk of colon cancer.

Benefits of cannabis

Cannabis has been cultivated and used by people for recreational and medicinal purposes since ancient eras for the past of hundreds of years. 23 The main component with medicinal purposes is cannabidiol (CBD). CBD attaches to the endocannabinoid system, potentially influencing the nervous system by triggering the release of hormones and other natural compounds like dopamine. As a result, marijuana may be useful in the management of several disorders such as anxiety, psychiatric disorders, pain, and obesity. 23

Several studies have discovered the efficacy of cannabis in alleviating pain. For example, a study conducted by Wallace et al 37 found that moderate use of marijuana with a THC content of 4% was associated with pain relief. However, high doses (7%THC) of marijuana were found to increase pain 38 and low doses (1% THC) of marijuana did not have any impact on pain levels. 12 , 37 The main cannabis element that is used for pain management is Anandamide, which acts as an autocrine or paracrine messenger. 38 The chemical is broken down into arachidonic acid and ethanolamine. The chemical can modulate nociceptive signals that cause pain by activating local CB1 receptors. 38 Marijuana could also be used as an alternative to opioids to relieve pain, despite its risk of addiction, but it is not life-threatening as opioids.

Chronic pain is among the major health issues with a high burden on individuals and society in the US. About half of the physician visits are due to chronic pain, resulting in a total medical cost of approximately $600 billion annually. 38 Pain is often described as a subjective experience that involves sensory-physiological, cognitive-evaluative, and motivational effective components. In humans, there are 3 main types of pain: nociceptive, neuropathic, and central. 38 , 39 Nociceptive pain is caused by damage to the tissue and is considered a defensive mechanism. On the other hand, neuropathic pain is caused by damage to the sensory and spinal nerves. Central pain is caused by consistent damage to the central nervous system amplifying pain signals from the periphery. 40

Other drugs have been used to treat pain, including alcohol and nicotine. However, discontinued use of addictive substances increases pain sensitivity. Marijuana reduces pain by binding CB1 and CB2 receptors that are activated by tissue injury. 38 It also reduces pain by binding to transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1) receptors which are mainly found in the nociceptive neurons of the peripheral nervous system. 39 TRPV1 receptors are also found in the central nervous system where they involve in the transmission and modulation of pain, as well as the integration of painful stimuli. 39

Targeting the endocannabinoid system to modulate pain is a promising way of managing pain, especially chronic pain. Anandamide (AEA) is also produced in injured cells, where it activates the local CB1 receptor, however, AEA is unable usually to activate all the CB1 receptors due to an enzyme called fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) which converts it into Ethanol-amide or arachidonic acid (AA). Exogenous cannabinoids (cannabis) inhibit the FAAH enzyme, and this allows more CB1 receptors activation. 4 Additionally, 2-arachidonoyl glycerol (2-AG) is activated by CB1 receptors and acts as a massager for pain. 38 Since 2-AG is an endocannabinoid, it plays a central role in modulating pain. Therefore, cannabis may suppress pain in a similar way to endocannabinoids by activating CB1 and CB2 receptors. 38 - 40

Several research studies have demonstrated that cannabis is remarkably proficient in alleviating pain. For example, a randomized controlled trial found that there is a therapeutic window for using marijuana to reduce pain, particularly when it is smoked. 12 However, another research suggests that oral forms of marijuana can also reduce pain. While the onset of effects may be slower compared to smoking, the pain relief provided by oral consumption is typically longer-lasting. 41 Additionally, in a different randomized clinical trial, it was observed that the individuals in the intervention group had greater pain relief than those in the placebo group. 42 Cannabis is commonly used to manage chronic pain in individuals with multiple sclerosis and arthritis. 42