How to write a research plan: Step-by-step guide

Last updated

30 January 2024

Reviewed by

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Today’s businesses and institutions rely on data and analytics to inform their product and service decisions. These metrics influence how organizations stay competitive and inspire innovation. However, gathering data and insights requires carefully constructed research, and every research project needs a roadmap. This is where a research plan comes into play.

Read this step-by-step guide for writing a detailed research plan that can apply to any project, whether it’s scientific, educational, or business-related.

- What is a research plan?

A research plan is a documented overview of a project in its entirety, from end to end. It details the research efforts, participants, and methods needed, along with any anticipated results. It also outlines the project’s goals and mission, creating layers of steps to achieve those goals within a specified timeline.

Without a research plan, you and your team are flying blind, potentially wasting time and resources to pursue research without structured guidance.

The principal investigator, or PI, is responsible for facilitating the research oversight. They will create the research plan and inform team members and stakeholders of every detail relating to the project. The PI will also use the research plan to inform decision-making throughout the project.

- Why do you need a research plan?

Create a research plan before starting any official research to maximize every effort in pursuing and collecting the research data. Crucially, the plan will model the activities needed at each phase of the research project .

Like any roadmap, a research plan serves as a valuable tool providing direction for those involved in the project—both internally and externally. It will keep you and your immediate team organized and task-focused while also providing necessary definitions and timelines so you can execute your project initiatives with full understanding and transparency.

External stakeholders appreciate a working research plan because it’s a great communication tool, documenting progress and changing dynamics as they arise. Any participants of your planned research sessions will be informed about the purpose of your study, while the exercises will be based on the key messaging outlined in the official plan.

Here are some of the benefits of creating a research plan document for every project:

Project organization and structure

Well-informed participants

All stakeholders and teams align in support of the project

Clearly defined project definitions and purposes

Distractions are eliminated, prioritizing task focus

Timely management of individual task schedules and roles

Costly reworks are avoided

- What should a research plan include?

The different aspects of your research plan will depend on the nature of the project. However, most official research plan documents will include the core elements below. Each aims to define the problem statement , devising an official plan for seeking a solution.

Specific project goals and individual objectives

Ideal strategies or methods for reaching those goals

Required resources

Descriptions of the target audience, sample sizes , demographics, and scopes

Key performance indicators (KPIs)

Project background

Research and testing support

Preliminary studies and progress reporting mechanisms

Cost estimates and change order processes

Depending on the research project’s size and scope, your research plan could be brief—perhaps only a few pages of documented plans. Alternatively, it could be a fully comprehensive report. Either way, it’s an essential first step in dictating your project’s facilitation in the most efficient and effective way.

- How to write a research plan for your project

When you start writing your research plan, aim to be detailed about each step, requirement, and idea. The more time you spend curating your research plan, the more precise your research execution efforts will be.

Account for every potential scenario, and be sure to address each and every aspect of the research.

Consider following this flow to develop a great research plan for your project:

Define your project’s purpose

Start by defining your project’s purpose. Identify what your project aims to accomplish and what you are researching. Remember to use clear language.

Thinking about the project’s purpose will help you set realistic goals and inform how you divide tasks and assign responsibilities. These individual tasks will be your stepping stones to reach your overarching goal.

Additionally, you’ll want to identify the specific problem, the usability metrics needed, and the intended solutions.

Know the following three things about your project’s purpose before you outline anything else:

What you’re doing

Why you’re doing it

What you expect from it

Identify individual objectives

With your overarching project objectives in place, you can identify any individual goals or steps needed to reach those objectives. Break them down into phases or steps. You can work backward from the project goal and identify every process required to facilitate it.

Be mindful to identify each unique task so that you can assign responsibilities to various team members. At this point in your research plan development, you’ll also want to assign priority to those smaller, more manageable steps and phases that require more immediate or dedicated attention.

Select research methods

Once you have outlined your goals, objectives, steps, and tasks, it’s time to drill down on selecting research methods . You’ll want to leverage specific research strategies and processes. When you know what methods will help you reach your goals, you and your teams will have direction to perform and execute your assigned tasks.

Research methods might include any of the following:

User interviews : this is a qualitative research method where researchers engage with participants in one-on-one or group conversations. The aim is to gather insights into their experiences, preferences, and opinions to uncover patterns, trends, and data.

Field studies : this approach allows for a contextual understanding of behaviors, interactions, and processes in real-world settings. It involves the researcher immersing themselves in the field, conducting observations, interviews, or experiments to gather in-depth insights.

Card sorting : participants categorize information by sorting content cards into groups based on their perceived similarities. You might use this process to gain insights into participants’ mental models and preferences when navigating or organizing information on websites, apps, or other systems.

Focus groups : use organized discussions among select groups of participants to provide relevant views and experiences about a particular topic.

Diary studies : ask participants to record their experiences, thoughts, and activities in a diary over a specified period. This method provides a deeper understanding of user experiences, uncovers patterns, and identifies areas for improvement.

Five-second testing: participants are shown a design, such as a web page or interface, for just five seconds. They then answer questions about their initial impressions and recall, allowing you to evaluate the design’s effectiveness.

Surveys : get feedback from participant groups with structured surveys. You can use online forms, telephone interviews, or paper questionnaires to reveal trends, patterns, and correlations.

Tree testing : tree testing involves researching web assets through the lens of findability and navigability. Participants are given a textual representation of the site’s hierarchy (the “tree”) and asked to locate specific information or complete tasks by selecting paths.

Usability testing : ask participants to interact with a product, website, or application to evaluate its ease of use. This method enables you to uncover areas for improvement in digital key feature functionality by observing participants using the product.

Live website testing: research and collect analytics that outlines the design, usability, and performance efficiencies of a website in real time.

There are no limits to the number of research methods you could use within your project. Just make sure your research methods help you determine the following:

What do you plan to do with the research findings?

What decisions will this research inform? How can your stakeholders leverage the research data and results?

Recruit participants and allocate tasks

Next, identify the participants needed to complete the research and the resources required to complete the tasks. Different people will be proficient at different tasks, and having a task allocation plan will allow everything to run smoothly.

Prepare a thorough project summary

Every well-designed research plan will feature a project summary. This official summary will guide your research alongside its communications or messaging. You’ll use the summary while recruiting participants and during stakeholder meetings. It can also be useful when conducting field studies.

Ensure this summary includes all the elements of your research project . Separate the steps into an easily explainable piece of text that includes the following:

An introduction: the message you’ll deliver to participants about the interview, pre-planned questioning, and testing tasks.

Interview questions: prepare questions you intend to ask participants as part of your research study, guiding the sessions from start to finish.

An exit message: draft messaging your teams will use to conclude testing or survey sessions. These should include the next steps and express gratitude for the participant’s time.

Create a realistic timeline

While your project might already have a deadline or a results timeline in place, you’ll need to consider the time needed to execute it effectively.

Realistically outline the time needed to properly execute each supporting phase of research and implementation. And, as you evaluate the necessary schedules, be sure to include additional time for achieving each milestone in case any changes or unexpected delays arise.

For this part of your research plan, you might find it helpful to create visuals to ensure your research team and stakeholders fully understand the information.

Determine how to present your results

A research plan must also describe how you intend to present your results. Depending on the nature of your project and its goals, you might dedicate one team member (the PI) or assume responsibility for communicating the findings yourself.

In this part of the research plan, you’ll articulate how you’ll share the results. Detail any materials you’ll use, such as:

Presentations and slides

A project report booklet

A project findings pamphlet

Documents with key takeaways and statistics

Graphic visuals to support your findings

- Format your research plan

As you create your research plan, you can enjoy a little creative freedom. A plan can assume many forms, so format it how you see fit. Determine the best layout based on your specific project, intended communications, and the preferences of your teams and stakeholders.

Find format inspiration among the following layouts:

Written outlines

Narrative storytelling

Visual mapping

Graphic timelines

Remember, the research plan format you choose will be subject to change and adaptation as your research and findings unfold. However, your final format should ideally outline questions, problems, opportunities, and expectations.

- Research plan example

Imagine you’ve been tasked with finding out how to get more customers to order takeout from an online food delivery platform. The goal is to improve satisfaction and retain existing customers. You set out to discover why more people aren’t ordering and what it is they do want to order or experience.

You identify the need for a research project that helps you understand what drives customer loyalty . But before you jump in and start calling past customers, you need to develop a research plan—the roadmap that provides focus, clarity, and realistic details to the project.

Here’s an example outline of a research plan you might put together:

Project title

Project members involved in the research plan

Purpose of the project (provide a summary of the research plan’s intent)

Objective 1 (provide a short description for each objective)

Objective 2

Objective 3

Proposed timeline

Audience (detail the group you want to research, such as customers or non-customers)

Budget (how much you think it might cost to do the research)

Risk factors/contingencies (any potential risk factors that may impact the project’s success)

Remember, your research plan doesn’t have to reinvent the wheel—it just needs to fit your project’s unique needs and aims.

Customizing a research plan template

Some companies offer research plan templates to help get you started. However, it may make more sense to develop your own customized plan template. Be sure to include the core elements of a great research plan with your template layout, including the following:

Introductions to participants and stakeholders

Background problems and needs statement

Significance, ethics, and purpose

Research methods, questions, and designs

Preliminary beliefs and expectations

Implications and intended outcomes

Realistic timelines for each phase

Conclusion and presentations

How many pages should a research plan be?

Generally, a research plan can vary in length between 500 to 1,500 words. This is roughly three pages of content. More substantial projects will be 2,000 to 3,500 words, taking up four to seven pages of planning documents.

What is the difference between a research plan and a research proposal?

A research plan is a roadmap to success for research teams. A research proposal, on the other hand, is a dissertation aimed at convincing or earning the support of others. Both are relevant in creating a guide to follow to complete a project goal.

What are the seven steps to developing a research plan?

While each research project is different, it’s best to follow these seven general steps to create your research plan:

Defining the problem

Identifying goals

Choosing research methods

Recruiting participants

Preparing the brief or summary

Establishing task timelines

Defining how you will present the findings

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 9 November 2024

Last updated: 11 January 2024

Last updated: 14 February 2024

Last updated: 27 January 2024

Last updated: 17 January 2024

Last updated: 14 November 2023

Last updated: 20 January 2024

Last updated: 19 November 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2024

Last updated: 25 November 2024

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, a whole new way to understand your customer is here, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

17 Research Proposal Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

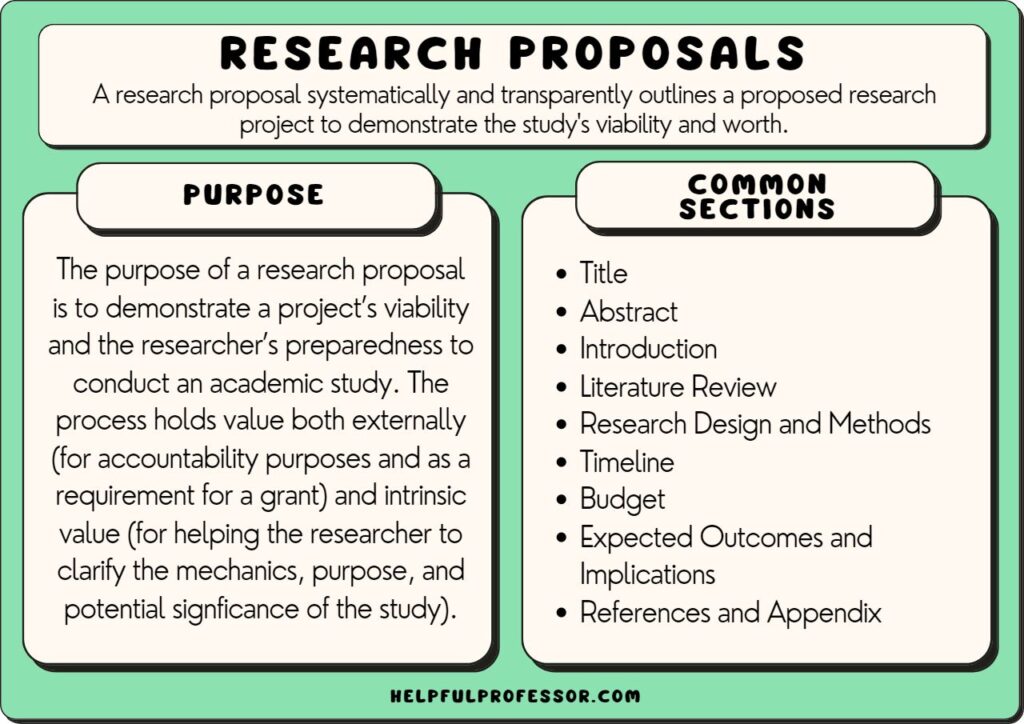

A research proposal systematically and transparently outlines a proposed research project.

The purpose of a research proposal is to demonstrate a project’s viability and the researcher’s preparedness to conduct an academic study. It serves as a roadmap for the researcher.

The process holds value both externally (for accountability purposes and often as a requirement for a grant application) and intrinsic value (for helping the researcher to clarify the mechanics, purpose, and potential signficance of the study).

Key sections of a research proposal include: the title, abstract, introduction, literature review, research design and methods, timeline, budget, outcomes and implications, references, and appendix. Each is briefly explained below.

Watch my Guide: How to Write a Research Proposal

Get your Template for Writing your Research Proposal Here (With AI Prompts!)

Research Proposal Sample Structure

Title: The title should present a concise and descriptive statement that clearly conveys the core idea of the research projects. Make it as specific as possible. The reader should immediately be able to grasp the core idea of the intended research project. Often, the title is left too vague and does not help give an understanding of what exactly the study looks at.

Abstract: Abstracts are usually around 250-300 words and provide an overview of what is to follow – including the research problem , objectives, methods, expected outcomes, and significance of the study. Use it as a roadmap and ensure that, if the abstract is the only thing someone reads, they’ll get a good fly-by of what will be discussed in the peice.

Introduction: Introductions are all about contextualization. They often set the background information with a statement of the problem. At the end of the introduction, the reader should understand what the rationale for the study truly is. I like to see the research questions or hypotheses included in the introduction and I like to get a good understanding of what the significance of the research will be. It’s often easiest to write the introduction last

Literature Review: The literature review dives deep into the existing literature on the topic, demosntrating your thorough understanding of the existing literature including themes, strengths, weaknesses, and gaps in the literature. It serves both to demonstrate your knowledge of the field and, to demonstrate how the proposed study will fit alongside the literature on the topic. A good literature review concludes by clearly demonstrating how your research will contribute something new and innovative to the conversation in the literature.

Research Design and Methods: This section needs to clearly demonstrate how the data will be gathered and analyzed in a systematic and academically sound manner. Here, you need to demonstrate that the conclusions of your research will be both valid and reliable. Common points discussed in the research design and methods section include highlighting the research paradigm, methodologies, intended population or sample to be studied, data collection techniques, and data analysis procedures . Toward the end of this section, you are encouraged to also address ethical considerations and limitations of the research process , but also to explain why you chose your research design and how you are mitigating the identified risks and limitations.

Timeline: Provide an outline of the anticipated timeline for the study. Break it down into its various stages (including data collection, data analysis, and report writing). The goal of this section is firstly to establish a reasonable breakdown of steps for you to follow and secondly to demonstrate to the assessors that your project is practicable and feasible.

Budget: Estimate the costs associated with the research project and include evidence for your estimations. Typical costs include staffing costs, equipment, travel, and data collection tools. When applying for a scholarship, the budget should demonstrate that you are being responsible with your expensive and that your funding application is reasonable.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: A discussion of the anticipated findings or results of the research, as well as the potential contributions to the existing knowledge, theory, or practice in the field. This section should also address the potential impact of the research on relevant stakeholders and any broader implications for policy or practice.

References: A complete list of all the sources cited in the research proposal, formatted according to the required citation style. This demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the relevant literature and ensures proper attribution of ideas and information.

Appendices (if applicable): Any additional materials, such as questionnaires, interview guides, or consent forms, that provide further information or support for the research proposal. These materials should be included as appendices at the end of the document.

Research Proposal Examples

Research proposals often extend anywhere between 2,000 and 15,000 words in length. The following snippets are samples designed to briefly demonstrate what might be discussed in each section.

1. Education Studies Research Proposals

See some real sample pieces:

- Assessment of the perceptions of teachers towards a new grading system

- Does ICT use in secondary classrooms help or hinder student learning?

- Digital technologies in focus project

- Urban Middle School Teachers’ Experiences of the Implementation of

- Restorative Justice Practices

- Experiences of students of color in service learning

Consider this hypothetical education research proposal:

The Impact of Game-Based Learning on Student Engagement and Academic Performance in Middle School Mathematics

Abstract: The proposed study will explore multiplayer game-based learning techniques in middle school mathematics curricula and their effects on student engagement. The study aims to contribute to the current literature on game-based learning by examining the effects of multiplayer gaming in learning.

Introduction: Digital game-based learning has long been shunned within mathematics education for fears that it may distract students or lower the academic integrity of the classrooms. However, there is emerging evidence that digital games in math have emerging benefits not only for engagement but also academic skill development. Contributing to this discourse, this study seeks to explore the potential benefits of multiplayer digital game-based learning by examining its impact on middle school students’ engagement and academic performance in a mathematics class.

Literature Review: The literature review has identified gaps in the current knowledge, namely, while game-based learning has been extensively explored, the role of multiplayer games in supporting learning has not been studied.

Research Design and Methods: This study will employ a mixed-methods research design based upon action research in the classroom. A quasi-experimental pre-test/post-test control group design will first be used to compare the academic performance and engagement of middle school students exposed to game-based learning techniques with those in a control group receiving instruction without the aid of technology. Students will also be observed and interviewed in regard to the effect of communication and collaboration during gameplay on their learning.

Timeline: The study will take place across the second term of the school year with a pre-test taking place on the first day of the term and the post-test taking place on Wednesday in Week 10.

Budget: The key budgetary requirements will be the technologies required, including the subscription cost for the identified games and computers.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: It is expected that the findings will contribute to the current literature on game-based learning and inform educational practices, providing educators and policymakers with insights into how to better support student achievement in mathematics.

2. Psychology Research Proposals

See some real examples:

- A situational analysis of shared leadership in a self-managing team

- The effect of musical preference on running performance

- Relationship between self-esteem and disordered eating amongst adolescent females

Consider this hypothetical psychology research proposal:

The Effects of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Stress Reduction in College Students

Abstract: This research proposal examines the impact of mindfulness-based interventions on stress reduction among college students, using a pre-test/post-test experimental design with both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods .

Introduction: College students face heightened stress levels during exam weeks. This can affect both mental health and test performance. This study explores the potential benefits of mindfulness-based interventions such as meditation as a way to mediate stress levels in the weeks leading up to exam time.

Literature Review: Existing research on mindfulness-based meditation has shown the ability for mindfulness to increase metacognition, decrease anxiety levels, and decrease stress. Existing literature has looked at workplace, high school and general college-level applications. This study will contribute to the corpus of literature by exploring the effects of mindfulness directly in the context of exam weeks.

Research Design and Methods: Participants ( n= 234 ) will be randomly assigned to either an experimental group, receiving 5 days per week of 10-minute mindfulness-based interventions, or a control group, receiving no intervention. Data will be collected through self-report questionnaires, measuring stress levels, semi-structured interviews exploring participants’ experiences, and students’ test scores.

Timeline: The study will begin three weeks before the students’ exam week and conclude after each student’s final exam. Data collection will occur at the beginning (pre-test of self-reported stress levels) and end (post-test) of the three weeks.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: The study aims to provide evidence supporting the effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions in reducing stress among college students in the lead up to exams, with potential implications for mental health support and stress management programs on college campuses.

3. Sociology Research Proposals

- Understanding emerging social movements: A case study of ‘Jersey in Transition’

- The interaction of health, education and employment in Western China

- Can we preserve lower-income affordable neighbourhoods in the face of rising costs?

Consider this hypothetical sociology research proposal:

The Impact of Social Media Usage on Interpersonal Relationships among Young Adults

Abstract: This research proposal investigates the effects of social media usage on interpersonal relationships among young adults, using a longitudinal mixed-methods approach with ongoing semi-structured interviews to collect qualitative data.

Introduction: Social media platforms have become a key medium for the development of interpersonal relationships, particularly for young adults. This study examines the potential positive and negative effects of social media usage on young adults’ relationships and development over time.

Literature Review: A preliminary review of relevant literature has demonstrated that social media usage is central to development of a personal identity and relationships with others with similar subcultural interests. However, it has also been accompanied by data on mental health deline and deteriorating off-screen relationships. The literature is to-date lacking important longitudinal data on these topics.

Research Design and Methods: Participants ( n = 454 ) will be young adults aged 18-24. Ongoing self-report surveys will assess participants’ social media usage, relationship satisfaction, and communication patterns. A subset of participants will be selected for longitudinal in-depth interviews starting at age 18 and continuing for 5 years.

Timeline: The study will be conducted over a period of five years, including recruitment, data collection, analysis, and report writing.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: This study aims to provide insights into the complex relationship between social media usage and interpersonal relationships among young adults, potentially informing social policies and mental health support related to social media use.

4. Nursing Research Proposals

- Does Orthopaedic Pre-assessment clinic prepare the patient for admission to hospital?

- Nurses’ perceptions and experiences of providing psychological care to burns patients

- Registered psychiatric nurse’s practice with mentally ill parents and their children

Consider this hypothetical nursing research proposal:

The Influence of Nurse-Patient Communication on Patient Satisfaction and Health Outcomes following Emergency Cesarians

Abstract: This research will examines the impact of effective nurse-patient communication on patient satisfaction and health outcomes for women following c-sections, utilizing a mixed-methods approach with patient surveys and semi-structured interviews.

Introduction: It has long been known that effective communication between nurses and patients is crucial for quality care. However, additional complications arise following emergency c-sections due to the interaction between new mother’s changing roles and recovery from surgery.

Literature Review: A review of the literature demonstrates the importance of nurse-patient communication, its impact on patient satisfaction, and potential links to health outcomes. However, communication between nurses and new mothers is less examined, and the specific experiences of those who have given birth via emergency c-section are to date unexamined.

Research Design and Methods: Participants will be patients in a hospital setting who have recently had an emergency c-section. A self-report survey will assess their satisfaction with nurse-patient communication and perceived health outcomes. A subset of participants will be selected for in-depth interviews to explore their experiences and perceptions of the communication with their nurses.

Timeline: The study will be conducted over a period of six months, including rolling recruitment, data collection, analysis, and report writing within the hospital.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: This study aims to provide evidence for the significance of nurse-patient communication in supporting new mothers who have had an emergency c-section. Recommendations will be presented for supporting nurses and midwives in improving outcomes for new mothers who had complications during birth.

5. Social Work Research Proposals

- Experiences of negotiating employment and caring responsibilities of fathers post-divorce

- Exploring kinship care in the north region of British Columbia

Consider this hypothetical social work research proposal:

The Role of a Family-Centered Intervention in Preventing Homelessness Among At-Risk Youthin a working-class town in Northern England

Abstract: This research proposal investigates the effectiveness of a family-centered intervention provided by a local council area in preventing homelessness among at-risk youth. This case study will use a mixed-methods approach with program evaluation data and semi-structured interviews to collect quantitative and qualitative data .

Introduction: Homelessness among youth remains a significant social issue. This study aims to assess the effectiveness of family-centered interventions in addressing this problem and identify factors that contribute to successful prevention strategies.

Literature Review: A review of the literature has demonstrated several key factors contributing to youth homelessness including lack of parental support, lack of social support, and low levels of family involvement. It also demonstrates the important role of family-centered interventions in addressing this issue. Drawing on current evidence, this study explores the effectiveness of one such intervention in preventing homelessness among at-risk youth in a working-class town in Northern England.

Research Design and Methods: The study will evaluate a new family-centered intervention program targeting at-risk youth and their families. Quantitative data on program outcomes, including housing stability and family functioning, will be collected through program records and evaluation reports. Semi-structured interviews with program staff, participants, and relevant stakeholders will provide qualitative insights into the factors contributing to program success or failure.

Timeline: The study will be conducted over a period of six months, including recruitment, data collection, analysis, and report writing.

Budget: Expenses include access to program evaluation data, interview materials, data analysis software, and any related travel costs for in-person interviews.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: This study aims to provide evidence for the effectiveness of family-centered interventions in preventing youth homelessness, potentially informing the expansion of or necessary changes to social work practices in Northern England.

Research Proposal Template

Get your Detailed Template for Writing your Research Proposal Here (With AI Prompts!)

This is a template for a 2500-word research proposal. You may find it difficult to squeeze everything into this wordcount, but it’s a common wordcount for Honors and MA-level dissertations.

Your research proposal is where you really get going with your study. I’d strongly recommend working closely with your teacher in developing a research proposal that’s consistent with the requirements and culture of your institution, as in my experience it varies considerably. The above template is from my own courses that walk students through research proposals in a British School of Education.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

8 thoughts on “17 Research Proposal Examples”

Very excellent research proposals

very helpful

Very helpful

Dear Sir, I need some help to write an educational research proposal. Thank you.

Hi Levi, use the site search bar to ask a question and I’ll likely have a guide already written for your specific question. Thanks for reading!

very good research proposal

Thank you so much sir! ❤️

Very helpful 👌

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

How to Write a Research Proposal: (with Examples & Templates)

Table of Contents

Before conducting a study, a research proposal should be created that outlines researchers’ plans and methodology and is submitted to the concerned evaluating organization or person. Creating a research proposal is an important step to ensure that researchers are on track and are moving forward as intended. A research proposal can be defined as a detailed plan or blueprint for the proposed research that you intend to undertake. It provides readers with a snapshot of your project by describing what you will investigate, why it is needed, and how you will conduct the research.

Your research proposal should aim to explain to the readers why your research is relevant and original, that you understand the context and current scenario in the field, have the appropriate resources to conduct the research, and that the research is feasible given the usual constraints.

This article will describe in detail the purpose and typical structure of a research proposal , along with examples and templates to help you ace this step in your research journey.

What is a Research Proposal ?

A research proposal¹ ,² can be defined as a formal report that describes your proposed research, its objectives, methodology, implications, and other important details. Research proposals are the framework of your research and are used to obtain approvals or grants to conduct the study from various committees or organizations. Consequently, research proposals should convince readers of your study’s credibility, accuracy, achievability, practicality, and reproducibility.

With research proposals , researchers usually aim to persuade the readers, funding agencies, educational institutions, and supervisors to approve the proposal. To achieve this, the report should be well structured with the objectives written in clear, understandable language devoid of jargon. A well-organized research proposal conveys to the readers or evaluators that the writer has thought out the research plan meticulously and has the resources to ensure timely completion.

Purpose of Research Proposals

A research proposal is a sales pitch and therefore should be detailed enough to convince your readers, who could be supervisors, ethics committees, universities, etc., that what you’re proposing has merit and is feasible . Research proposals can help students discuss their dissertation with their faculty or fulfill course requirements and also help researchers obtain funding. A well-structured proposal instills confidence among readers about your ability to conduct and complete the study as proposed.

Research proposals can be written for several reasons:³

- To describe the importance of research in the specific topic

- Address any potential challenges you may encounter

- Showcase knowledge in the field and your ability to conduct a study

- Apply for a role at a research institute

- Convince a research supervisor or university that your research can satisfy the requirements of a degree program

- Highlight the importance of your research to organizations that may sponsor your project

- Identify implications of your project and how it can benefit the audience

What Goes in a Research Proposal?

Research proposals should aim to answer the three basic questions—what, why, and how.

The What question should be answered by describing the specific subject being researched. It should typically include the objectives, the cohort details, and the location or setting.

The Why question should be answered by describing the existing scenario of the subject, listing unanswered questions, identifying gaps in the existing research, and describing how your study can address these gaps, along with the implications and significance.

The How question should be answered by describing the proposed research methodology, data analysis tools expected to be used, and other details to describe your proposed methodology.

Research Proposal Example

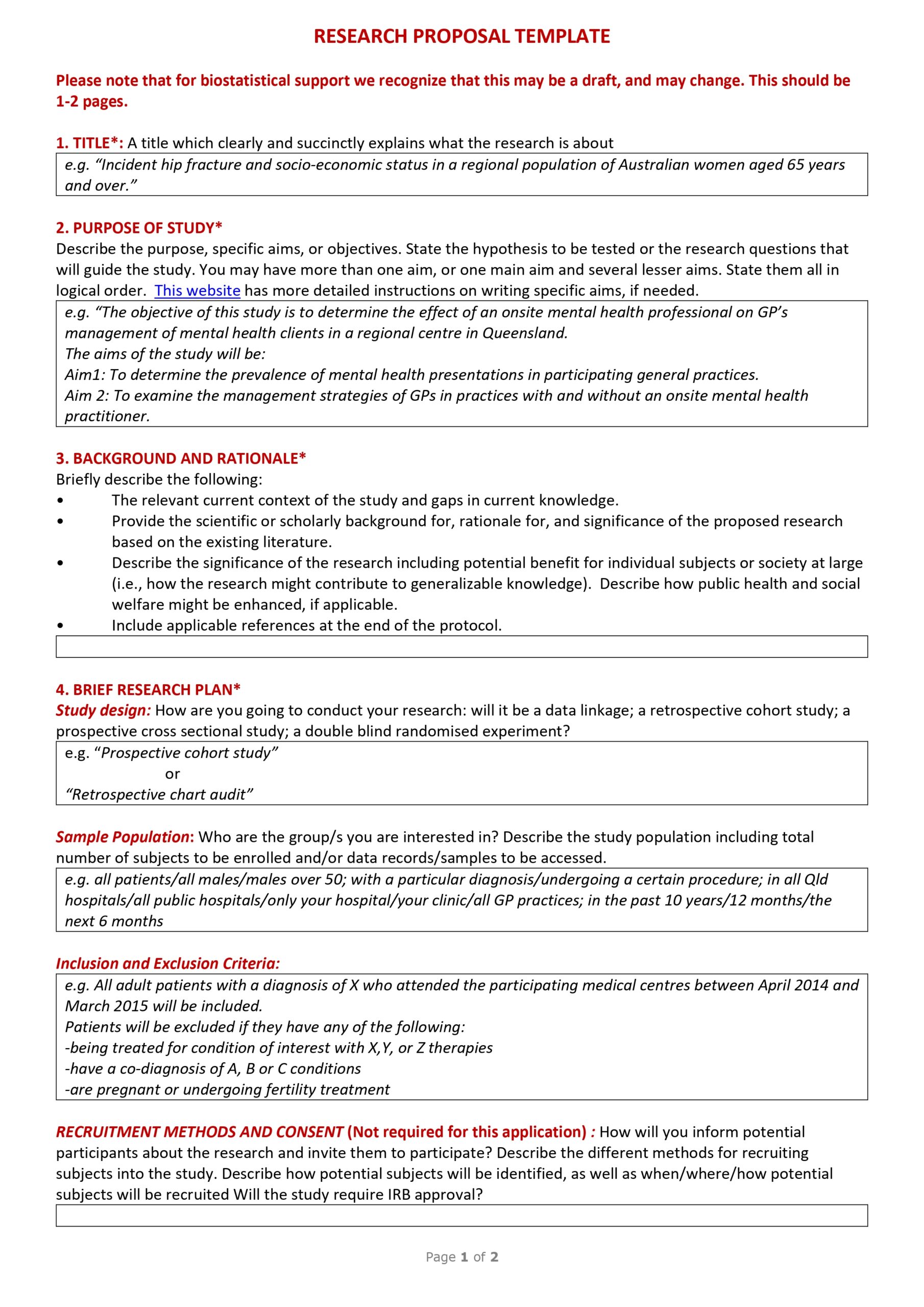

Here is a research proposal sample template (with examples) from the University of Rochester Medical Center. 4 The sections in all research proposals are essentially the same although different terminology and other specific sections may be used depending on the subject.

Structure of a Research Proposal

If you want to know how to make a research proposal impactful, include the following components:¹

1. Introduction

This section provides a background of the study, including the research topic, what is already known about it and the gaps, and the significance of the proposed research.

2. Literature review

This section contains descriptions of all the previous relevant studies pertaining to the research topic. Every study cited should be described in a few sentences, starting with the general studies to the more specific ones. This section builds on the understanding gained by readers in the Introduction section and supports it by citing relevant prior literature, indicating to readers that you have thoroughly researched your subject.

3. Objectives

Once the background and gaps in the research topic have been established, authors must now state the aims of the research clearly. Hypotheses should be mentioned here. This section further helps readers understand what your study’s specific goals are.

4. Research design and methodology

Here, authors should clearly describe the methods they intend to use to achieve their proposed objectives. Important components of this section include the population and sample size, data collection and analysis methods and duration, statistical analysis software, measures to avoid bias (randomization, blinding), etc.

5. Ethical considerations

This refers to the protection of participants’ rights, such as the right to privacy, right to confidentiality, etc. Researchers need to obtain informed consent and institutional review approval by the required authorities and mention this clearly for transparency.

6. Budget/funding

Researchers should prepare their budget and include all expected expenditures. An additional allowance for contingencies such as delays should also be factored in.

7. Appendices

This section typically includes information that supports the research proposal and may include informed consent forms, questionnaires, participant information, measurement tools, etc.

8. Citations

Always ensure to cite all sources referred to while writing the proposal. Any citation method could be used as long as it is consistent and adheres to a specific format.

Important Tips for Writing a Research Proposal

Writing a research proposal begins much before the actual task of writing. Planning the research proposal structure and content is an important stage, which if done efficiently, can help you seamlessly transition into the writing stage. 3,5

The Planning Stage

- Manage your time efficiently. Plan to have the draft version ready at least two weeks before your deadline and the final version at least two to three days before the deadline.

- What is the primary objective of your research?

- Will your research address any existing gap?

- What is the impact of your proposed research?

- Do people outside your field find your research applicable in other areas?

- If your research is unsuccessful, would there still be other useful research outcomes?

The Writing Stage

- Create an outline with main section headings that are typically used.

- Focus only on writing and getting your points across without worrying about the format of the research proposal , grammar, punctuation, etc. These can be fixed during the subsequent passes. Add details to each section heading you created in the beginning.

- Ensure your sentences are concise and use plain language. A research proposal usually contains about 2,000 to 4,000 words or four to seven pages.

- Don’t use too many technical terms and abbreviations assuming that the readers would know them. Define the abbreviations and technical terms.

- Ensure that the entire content is readable. Avoid using long paragraphs because they affect the continuity in reading. Break them into shorter paragraphs and introduce some white space for readability.

- Focus on only the major research issues and cite sources accordingly. Don’t include generic information or their sources in the literature review.

- Proofread your final document to ensure there are no grammatical errors so readers can enjoy a seamless, uninterrupted read.

- Use academic, scholarly language because it brings formality into a document.

- Ensure that your title is created using the keywords in the document and is neither too long and specific nor too short and general.

- Cite all sources appropriately to avoid plagiarism.

- Make sure that you follow guidelines, if provided. This includes rules as simple as using a specific font or a hyphen or en dash between numerical ranges.

- Ensure that you’ve answered all questions requested by the evaluating authority.

Key Takeaways

Here’s a summary of the main points about research proposals discussed in the previous sections:

- A research proposal is a document that outlines the details of a proposed study and is created by researchers to submit to evaluators who could be research institutions, universities, faculty, etc.

- Research proposals are usually about 2,000-4,000 words long, but this depends on the evaluating authority’s guidelines.

- A good research proposal ensures that you’ve done your background research and assessed the feasibility of the research.

- Research proposals have the following main sections—introduction, literature review, objectives, methodology, ethical considerations, and budget.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1. How is a research proposal evaluated?

A1. In general, most evaluators, including universities, broadly use the following criteria to evaluate research proposals . 6

- Significance —Does the research address any important subject or issue, which may or may not be specific to the evaluator or university?

- Content and design —Is the proposed methodology appropriate to answer the research question? Are the objectives clear and well aligned with the proposed methodology?

- Sample size and selection —Is the target population or cohort size clearly mentioned? Is the sampling process used to select participants randomized, appropriate, and free of bias?

- Timing —Are the proposed data collection dates mentioned clearly? Is the project feasible given the specified resources and timeline?

- Data management and dissemination —Who will have access to the data? What is the plan for data analysis?

Q2. What is the difference between the Introduction and Literature Review sections in a research proposal ?

A2. The Introduction or Background section in a research proposal sets the context of the study by describing the current scenario of the subject and identifying the gaps and need for the research. A Literature Review, on the other hand, provides references to all prior relevant literature to help corroborate the gaps identified and the research need.

Q3. How long should a research proposal be?

A3. Research proposal lengths vary with the evaluating authority like universities or committees and also the subject. Here’s a table that lists the typical research proposal lengths for a few universities.

Q4. What are the common mistakes to avoid in a research proposal ?

A4. Here are a few common mistakes that you must avoid while writing a research proposal . 7

- No clear objectives: Objectives should be clear, specific, and measurable for the easy understanding among readers.

- Incomplete or unconvincing background research: Background research usually includes a review of the current scenario of the particular industry and also a review of the previous literature on the subject. This helps readers understand your reasons for undertaking this research because you identified gaps in the existing research.

- Overlooking project feasibility: The project scope and estimates should be realistic considering the resources and time available.

- Neglecting the impact and significance of the study: In a research proposal , readers and evaluators look for the implications or significance of your research and how it contributes to the existing research. This information should always be included.

- Unstructured format of a research proposal : A well-structured document gives confidence to evaluators that you have read the guidelines carefully and are well organized in your approach, consequently affirming that you will be able to undertake the research as mentioned in your proposal.

- Ineffective writing style: The language used should be formal and grammatically correct. If required, editors could be consulted, including AI-based tools such as Paperpal , to refine the research proposal structure and language.

Thus, a research proposal is an essential document that can help you promote your research and secure funds and grants for conducting your research. Consequently, it should be well written in clear language and include all essential details to convince the evaluators of your ability to conduct the research as proposed.

This article has described all the important components of a research proposal and has also provided tips to improve your writing style. We hope all these tips will help you write a well-structured research proposal to ensure receipt of grants or any other purpose.

References

- Sudheesh K, Duggappa DR, Nethra SS. How to write a research proposal? Indian J Anaesth. 2016;60(9):631-634. Accessed July 15, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5037942/

- Writing research proposals. Harvard College Office of Undergraduate Research and Fellowships. Harvard University. Accessed July 14, 2024. https://uraf.harvard.edu/apply-opportunities/app-components/essays/research-proposals

- What is a research proposal? Plus how to write one. Indeed website. Accessed July 17, 2024. https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/research-proposal

- Research proposal template. University of Rochester Medical Center. Accessed July 16, 2024. https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/MediaLibraries/URMCMedia/pediatrics/research/documents/Research-proposal-Template.pdf

- Tips for successful proposal writing. Johns Hopkins University. Accessed July 17, 2024. https://research.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Tips-for-Successful-Proposal-Writing.pdf

- Formal review of research proposals. Cornell University. Accessed July 18, 2024. https://irp.dpb.cornell.edu/surveys/survey-assessment-review-group/research-proposals

- 7 Mistakes you must avoid in your research proposal. Aveksana (via LinkedIn). Accessed July 17, 2024. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/7-mistakes-you-must-avoid-your-research-proposal-aveksana-cmtwf/

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- How to Write a PhD Research Proposal

- What are the Benefits of Generative AI for Academic Writing?

- How to Avoid Plagiarism When Using Generative AI Tools

- What is Hedging in Academic Writing?

How to Write Your Research Paper in APA Format

The future of academia: how ai tools are changing the way we do research, you may also like, how to write a thematic literature review, chicago style citation guide: understanding the chicago manual..., what is the purpose of an abstract why..., what are citation styles which citation style to..., what are the types of literature reviews , abstract vs introduction: what is the difference , mla format: guidelines, template and examples , machine translation vs human translation: which is reliable..., dissertation printing and binding | types & comparison , what is a dissertation preface definition and examples .

- CREd Library , Planning, Managing, and Publishing Research

Developing a Five-Year Research Plan

Cathy binger and lizbeth finestack, doi: 10.1044/cred-pvd-path006.

The following is a transcript of the presentation videos, edited for clarity.

What Is a Research Plan, and Why Do You Need One?

Presented by Cathy Binger

First we’re going to talk about what a research plan is, why it’s important to write one, and why five years—why not one year, why not ten years. So we’ll do some of those basic things, then Liza is going to get down and dirty into the nitty-gritty of “now what” how do I go about writing that research plan.

First of all, what is a research plan? I’m sure some of you have taken a stab at these already. In case you haven’t, this is a real personalized map that relates your projects to goals. It’s exactly what it sounds like, it’s a plan of how you’re going to go about doing your research. It doesn’t necessarily just include research.

It’s something that you need to put a little time and effort into in the beginning. And then, if you don’t revisit it, it’s really a useless document. It’s something that you need to come back to repeatedly, at least annually, and you need to make it visible. So it’s not a document that sits around and once a year you pull it out and look at it.

It can and should be designed, especially initially, with the help of a mentor or colleague. And it does serve multiple purposes, with different lengths and different amounts of detail.

I forgot to say, too, getting started, the slides for this talk were started using as a jumping off point Ray Kent’s talk from last year. So some of the slides we’ve borrowed from him, so many thanks to him for that.

But why do we want to do a research plan? Well, to me the big thing is the vision. Dr. Barlow talked this morning about your line of research and really knowing where you want to go, and this is where that shows up with all the nuts and bolts in place.

What do you want to accomplish? What do you want to contribute? Most of you are at the stage in your career where maybe you have started out with that you want to change the world scenario and realized that whatever you wanted your first research project to be, really, is your entire career. You need to get that down to the point where it is manageable projects that you can do—this is where you map out what those projects are and set reasonable timelines for that.

You want to really demonstrate your independent thinking and your own creativity, whatever that is that you then establish as a PhD student, postdoc, and beyond—this is where you come back to, okay, here’s how I’m going to go about achieving all of that.

This next point, learning to realistically gauge how long it takes to achieve each goal, this for most of us is a phenomenally challenging thing to do. Most of us really overestimate what we can do in a certain amount of time, and we learn the hard way that you can’t, and that’s another reason why you keep coming back to these plans repeatedly and learning over time what’s really manageable, what’s really doable, so we can still reach our goals and be very strategic about how we do that.

When you’re not strategic, you just don’t meet the goals. Your time gets sucked into so many different things. We need to be really practical and strategic.

Everything we do is going to take longer than we think.

I think this last one is something that maybe we don’t talk about enough. Really being honest with ourselves about the role of research in our lives. Not all of you are at very high-level research universities. Some of you have chosen to go elsewhere, where research maybe isn’t going to be playing the same role as it is for other people. The research plan for someone at an R One research intensive university is going to look quite different from someone who is at a primary teaching university. We need to be open and practical about that.

Getting sidetracked. I love this picture, I just found this picture the other day. This feels like my life. You can get pulled in so many different directions once you are a professor. You will get asked to do a thousand different things. There are lots of great opportunities that are out there. Especially initially, it’s tempting to say yes to all of them. But if you’re going to be productive, you have to be very strategic. I’m going to be a little bit sexist against my own sex here for a minute, but my observation has been that women tend to fall into this a little bit more than men do in wanting to say yes and be people pleasers for everything that comes down the pike.

It is a professional skill to learn how to say no. And to do that in such a way that you are not burning bridges as you go down the path. That is a critical skill if you are going to be a successful researcher. I can’t tell you how many countless people I’ve seen who are very bright, very dedicated, have the skills that it takes in terms of doing the work—but then they are not successful because they’ve gotten sidetracked and they try to be too much of a good citizen, give too much service to the department, too much “sure I’ll take on that extra class” or whatever else comes down the line.

I just spoke with a professor recently who had something like five hours a week of office hours scheduled every single week for one class. Margaret is shaking her head like “are you kidding?” That’s crazy stuff. But he wanted to really support his students. His students loved him, but he was not going to get tenure. That’s the story.

So we have to be very thoughtful and strategic, and what can help you with this, and ASHA very firmly recognizes which is why we’re here—is that your mentors in your life should be there to help you learn these skills and learn what to say yes to, and learn what to say no to. I’ve learned to say things like, “Let me check with my mentor before I agree to that.” And it gives you a way out of that. The line that I use a lot is, “Let me check with my department head” or, I just said this to somebody last week, “I just promised my department head two weeks ago that I would only do X number of external workshops this year, so I’m going to have to turn this one down.” Those are really important skills to develop.

And having that research plan in place that you can go back to and say, know what, it’s not on my plan I can’t do it. If I do it—I have to go back to my research plan and figure out what I’m going to kick off in order to review this extra paper, in order to take on this extra task. The plan also helps me to know exactly what to say no to. And to be very direct and have a very strong visual.

I actually have my research plan up on a giant whiteboard in my office, so I can always go back to that and see where I am, and I can say, “Okay, what am I going to kick off of here? Nothing. Okay, I have to say no to whatever comes up.” Just be strategic. This is where I see most beginning professors really end up taking that wrong fork in the road—taking that right instead of that left, and ending up not being the successful researcher that they wanted to be.

What evidence supports research planning? This was something Ray Kent had found. That a recent analysis had found that postdoc scholars who developed a written plan with their postdoc advisers were much more productive than those who didn’t. And your performance during a postdoc—and I know many of you have either finished your postdoc or decided not to—so more simply, just during those first six years, the decisions you make really do establish the foundation for the rest of your professional life. It’s very important to get started and get off on the right foot.

I love this quote, I just found it the other day: “Productivity is never an accident. It is always the result of a commitment to excellence, intelligent planning, and focused effort.”

What we see with productivity is that postdoc scholars who developed written productivity expectations with their advisers were more productive than those who didn’t. You see 23% more papers submitted, 30% more first-author papers, and more grant proposals as well.

So why five years? I’m going to start with number 5. It’s long enough to build a program of research, but short enough to deal with changing circumstances. That’s really the long and the short of the matter. As well as these other things as well that I won’t take the time to go through point by point.

What Should a Five-Year Plan Include?

Presented by Lizbeth Finestack

So, thinking about a five-year research plan, I like to think about it like your major “To Do List.” It’s what you’re going to accomplish in five years. Start thinking: What is going to be on my to do list?

You can also think about it like: Okay, I have research. I’ve got to do research. Maybe think about this as one big bucket, or maybe one humongous silo. I have some farm themes going on. Cathy was just on a farm, so I thought I’d tie that in.

So here’s your big silo. You can call that your research silo.

But more realistically, you need to think about it like separate buckets, separate silos, where research is just one of those. Just like Cathy indicated, there’s going to be lots of other things coming up that you’re going to have to manage. They are going to have to be on your to do list, you need to figure out how to fit everything in.

What all those other buckets or silos are, are really going to depend on your job. And maybe the size of the silos, and the size of the buckets are going to vary depending on where you are, what the expectations are at your institution.

That’s important to keep in mind, and Cathy said this too, it’s not going to be the same for everyone. The five-year plan has to be your plan, your to do list.

Here are some buckets or some silos that I have on my list and the way that I break it up, this is just one example, take it or leave it.

The first three are all very closely related, right? Thinking about grants, thinking about research, thinking about publications. I’m going to define grants as actual writing, getting the grant, getting the money.

Research is what you’re going to do once you get that money. Steps you need to take before you are getting the money. Any sorts of projects, the lab work, that’s why I have the lab picture there. Of course, publications are part of the product—what’s coming out of the research—but it also cycles in because you need publications to support that you are a researcher to apply for funding and show you have this line of research that you’ve established and you’ll be able to continue. So, those first three are really closely related. And that’s where I’ll go next. And then have teaching and service you see here at the bottom.

So thinking about research, in that broad sense. As you’re writing your five-year plan you’re going to want to think of, “What’s my long-term goal?” There’s lots of ways to think of long-term goals. You could think, before I die, this is what I want to accomplish. For me I kind of have that. My long-term goal is that I’m going to find the most effective and efficient interventions for kids with language impairment. Huge broad goal. But within that I can start narrowing it down.

Where am I within that? Within the next five years or maybe the next ten years, what is it I want to accomplish towards that goal. Then start thinking about: In order to accomplish that goal, what are the steps I need to take? Starting to break it down a little bit. Then it’s also going to be really important to think: where are you going to start? Where are you now? What do you need to have happen? And is it reasonable to accomplish this goal within five years? Is it going to take longer? Maybe you could do it in a couple years? Start thinking about the timeline that’s going to work for you.

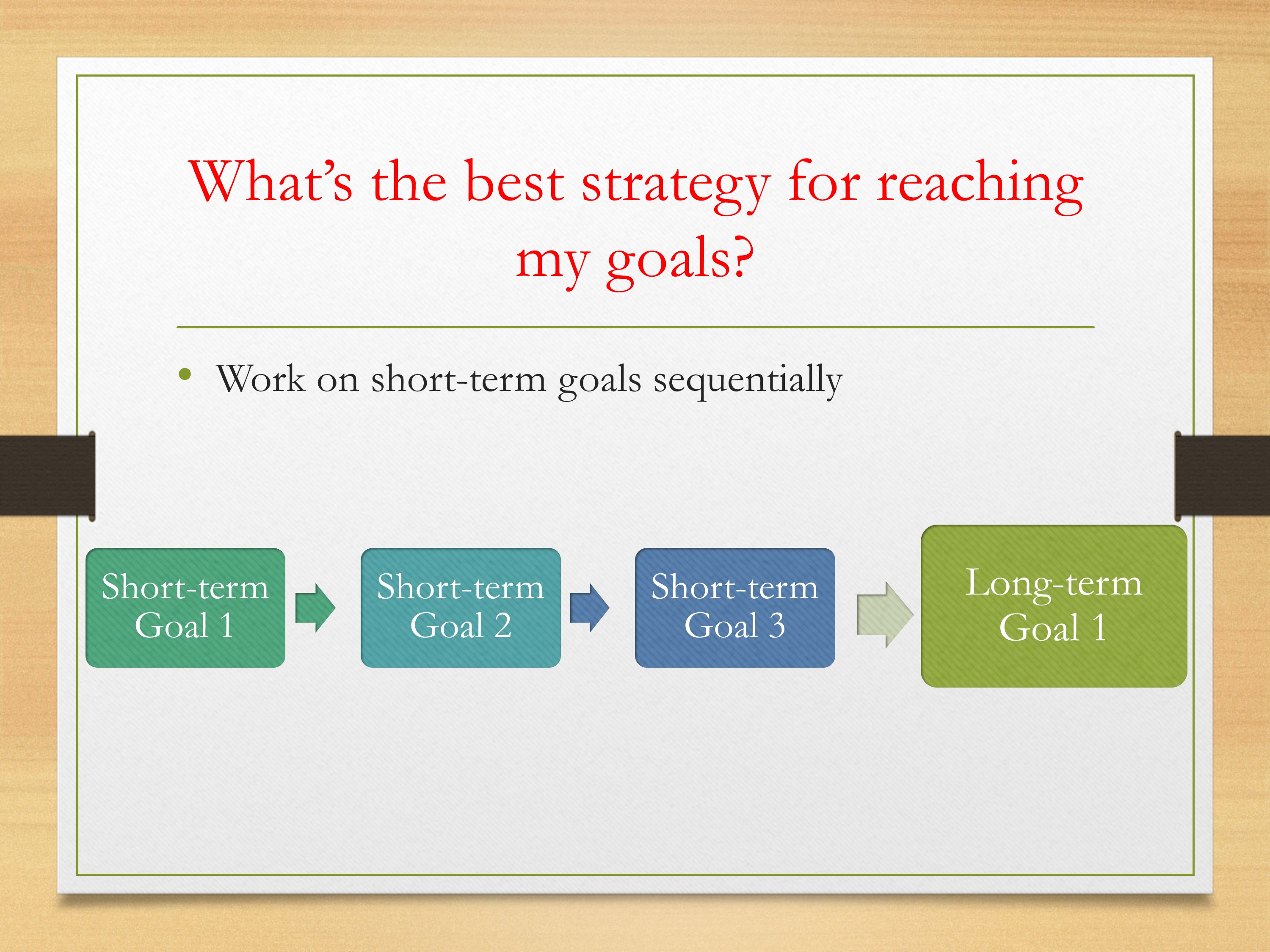

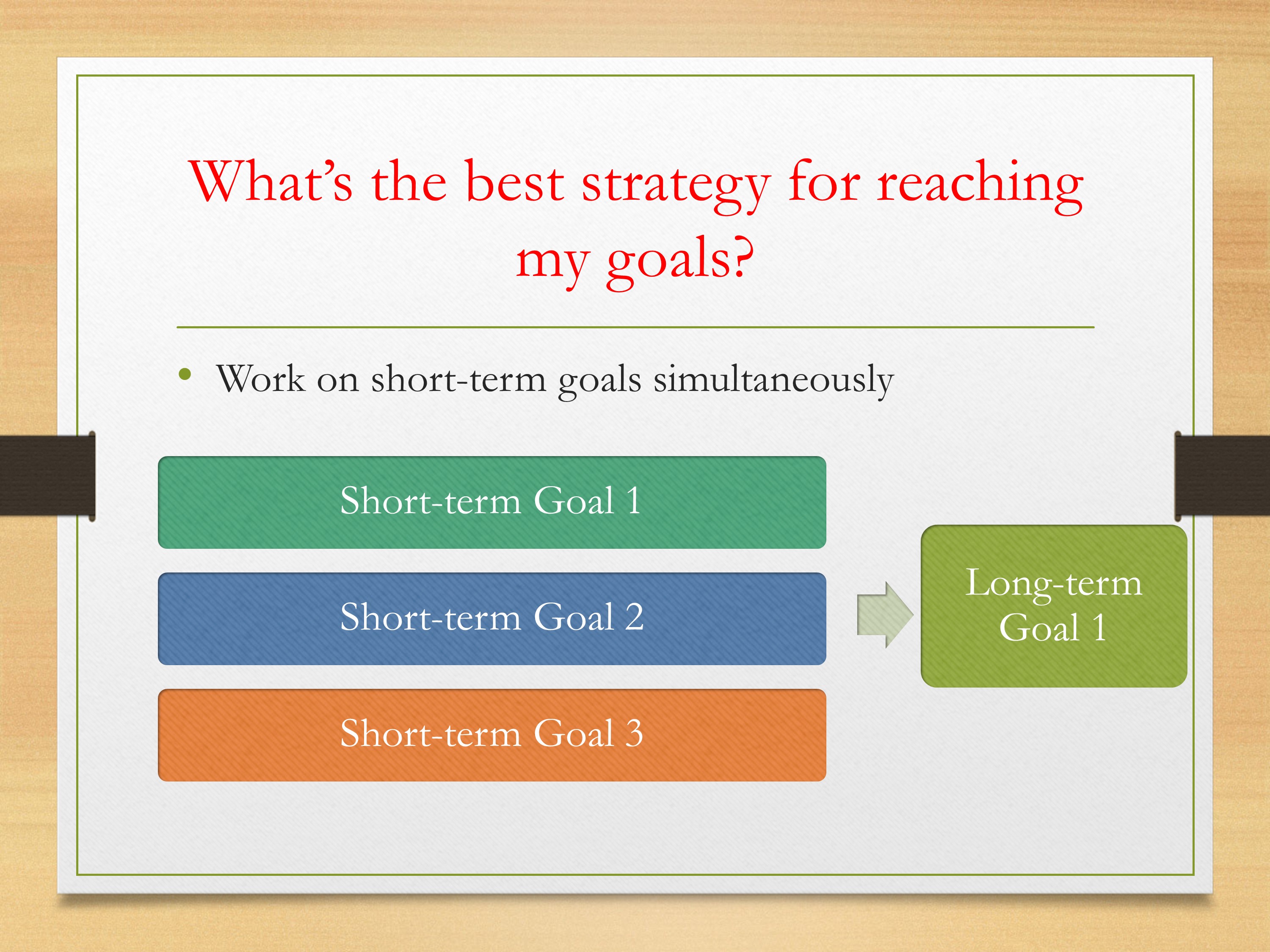

Then thinking about your goals—and everyone’s program is going to be different, like I said, there’s going to be a lot of individual needs, preferences. So it might be the case that you have this one long-term goal that you’re aiming for. Long-term goal in the sense of, maybe, what you want to study in your R01, perhaps something like that. But in order to get to that point, you’re going to have several short-term goals that need to be accomplished.

Or maybe it’s the case that you have two long-term goals. And with each of those you’re going to have multiple short-term goals that you’re working on. Maybe the scope of each of these long-term goals is a little bit less than in that first scenario.

Start thinking about my research, what I want to do, and how it might fit into these different circumstances.

Also thinking about your goals, this is a slide from Ray Kent from last year, was thinking about the different types of projects you might want to pursue, and thinking about ones that are definitely well on your way. They are safe bets. You have some funding. They are going to lead directly into your longer-term plan.

Those are going to be your front burner—things you can easily focus on. That said, don’t put everything there.

You can also have things on the back burner. Things that really excite you, might have huge benefits, big pay. But you don’t want to spend all of your time there because they could be pretty risky.

Start thinking about where you’re putting your time. Are you putting it all on this high-risk thing that if it doesn’t pan out you’re going to be in big trouble? Or balancing that somewhat with your front burner. Making that steady progress that will lead directly to help fund an R01 or whatever the mechanism that you’re looking for.

Then, thinking about your goals—if you have multiple long-term goals, or thinking about your short-term goals, you could think about your process. Is it something where you need to do study 1 then study 2, then study 3—each of those building on each other, that’s leading to that long-term goal. In many cases, that is the case, where you have to get information from the first study which is going to lead directly to the second study and so forth.

Or is it the case that you can be working on these three short-term goals simultaneously? Spreading your resources at the same time. Maybe it will take longer for any one study, but across a longer period of time you’ll get the information that you need to reach that long-term goal.

Lots and lots of different ways to go about it. The important thing is to think about what your needs are and what makes the most sense for you.

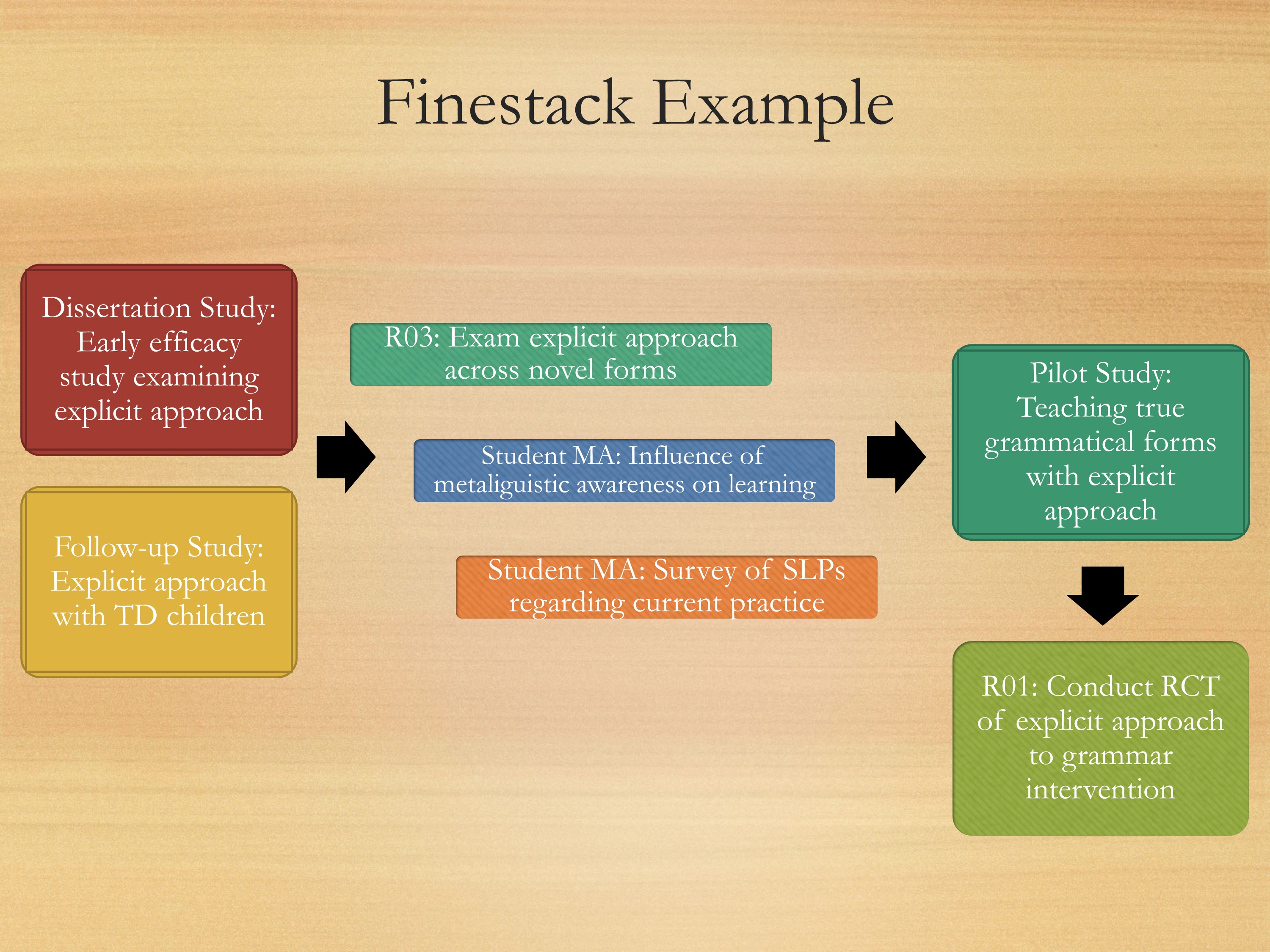

Here’s my own little personal example. Starting over here, I have my dissertation study. My dissertation study was this early efficacy study looking at one treatment approach using novel forms that really can’t generalize to anything too useful, but it was important.

Then I did a follow up study, where I was taking that same paradigm, looking to see where kids with typical development perform on the task. So I have these two studies, and they served as my preliminary studies for an R03. So I just finished an R03 where I was looking at different treatment approaching for kids with primary language impairment. At the same time, while conducting my R03, I’m also looking at some different approaches that might help with language development. Also conducting surveys to see what current practices are.

I have these three projects going on simultaneously, that are going to lead to a bigger pilot study that are going to feed directly into my R01. All of this will serve as preliminary data to go into an R01.

Start thinking about your projects, what you have. Maybe starting with your dissertation project or work that you’re doing as a postdoc as seeing how that can feed into your long-term goal. And really utilizing it, building on it, to your benefit.

That’s all fine and dandy. You can draw these great pictures. But you still have to break it down some more. It’s not like, “Oh, I’m just going to do this project.” There are other steps involved, and lots of the time these steps are going to be just as time consuming.

Starting to think about: well, if you have the funding. Saying, “I want to do this study, but I have no money to do it.” What are the steps in order to get the money to do it? Do you have a pilot study? What do you need?

Start thinking about the resources? Do you need to develop stimuli, protocols, procedures? Start working on that. All of these can be very time consuming, and if you don’t jump on that immediately, it’s going to delay when you can start that project.

Thinking about IRB. Relationships for recruitment, if you’re working with special populations especially? Do you have necessary personnel, grad students, people to help you with the project? Do you need to train them? What’s the timeline of the study?

Start thinking about all these pieces, and how they are going to fit in that timeline.

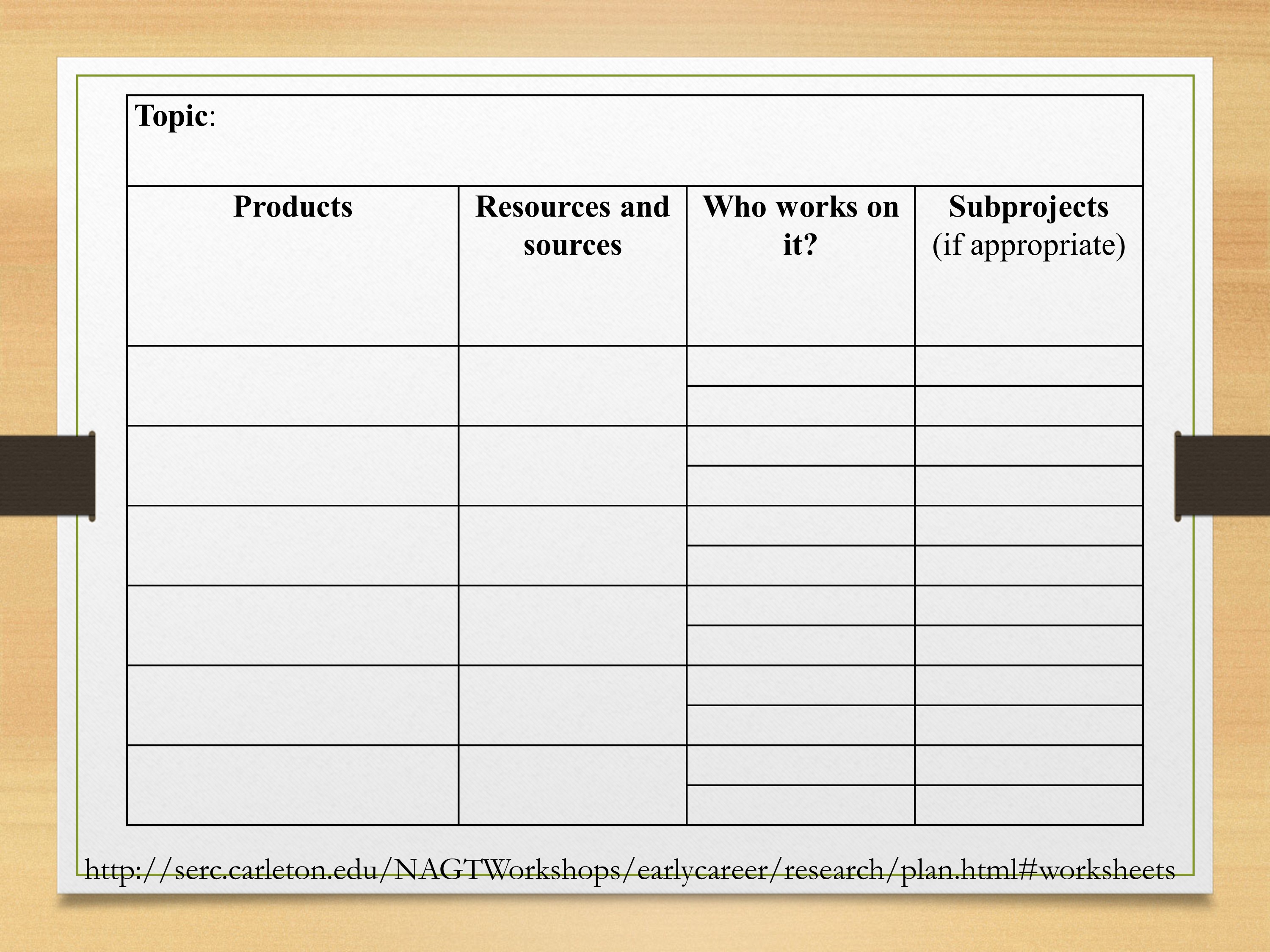

This is one way that might help you start thinking about the resources that you need. This is online—Ray Kent had it in his talk, and when I was doing my searches I came across it too and I have the website at the end. Just different ways to think about the resources you might need.

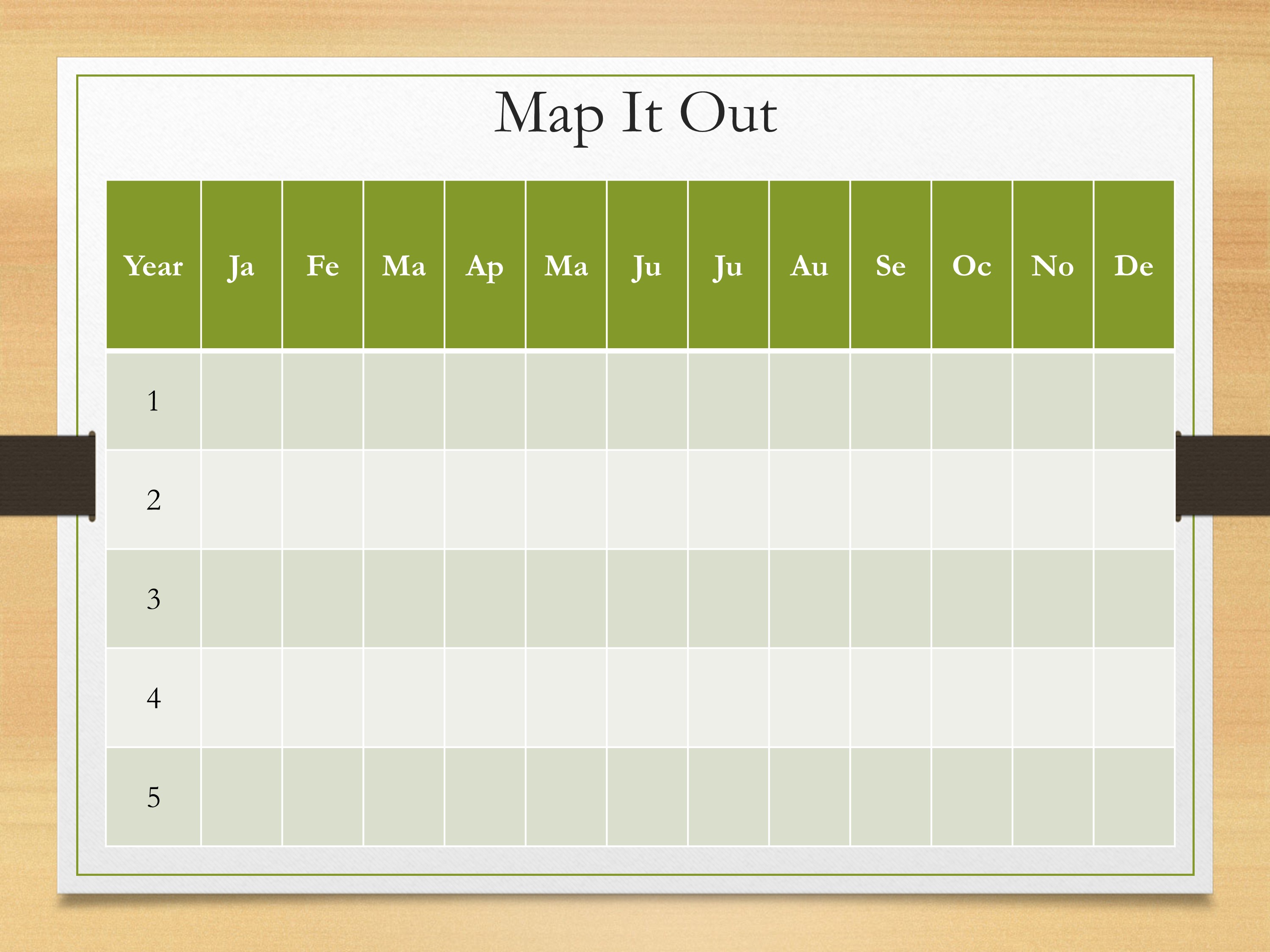

Let’s talk about mapping it out. You have your long-term goal. You have your short-term goals. You’re breaking it down thinking about all those little steps that you need to accomplish. We gotta put it on a calendar. When is it going to happen?

This is an example—you might have your five years. Each month plugging in what are you going to accomplish by that time. Maybe it’s when are grant applications due? It’s going to be important to put those on there to go what do I need to do to make that deadline. Maybe it’s putting when you’re going to get publications out. Things like that.

Honestly, looking at this drives me a little bit crazy, it seems a bit overwhelming. But it’s important to get to these details.

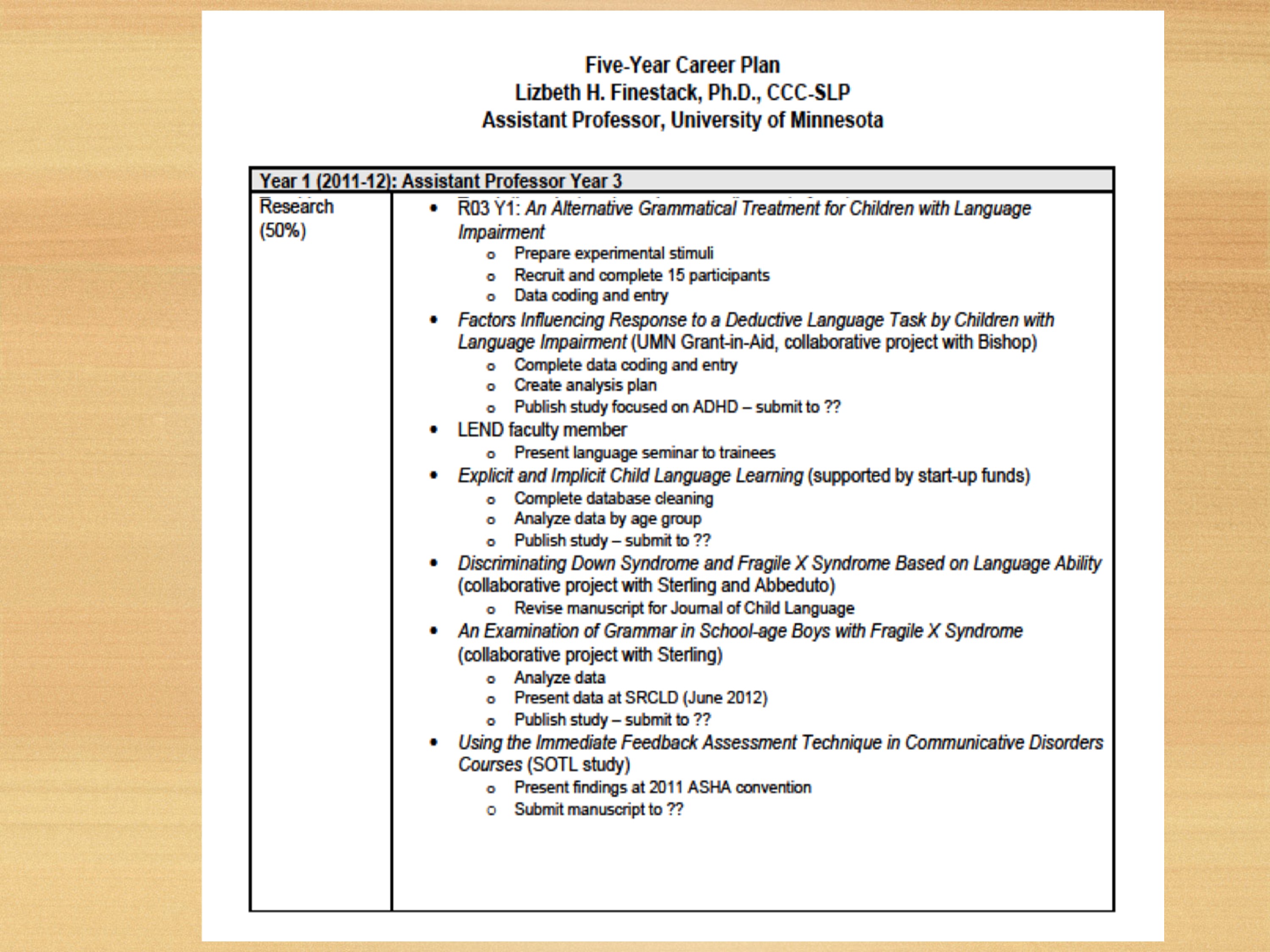

This is an example from, I did Lessons for Success a few years ago and they had their format for doing your plan. I wrote out all my projects, started thinking about all the different aspects. So if something like this works for you, by all means you could use that type of procedure.

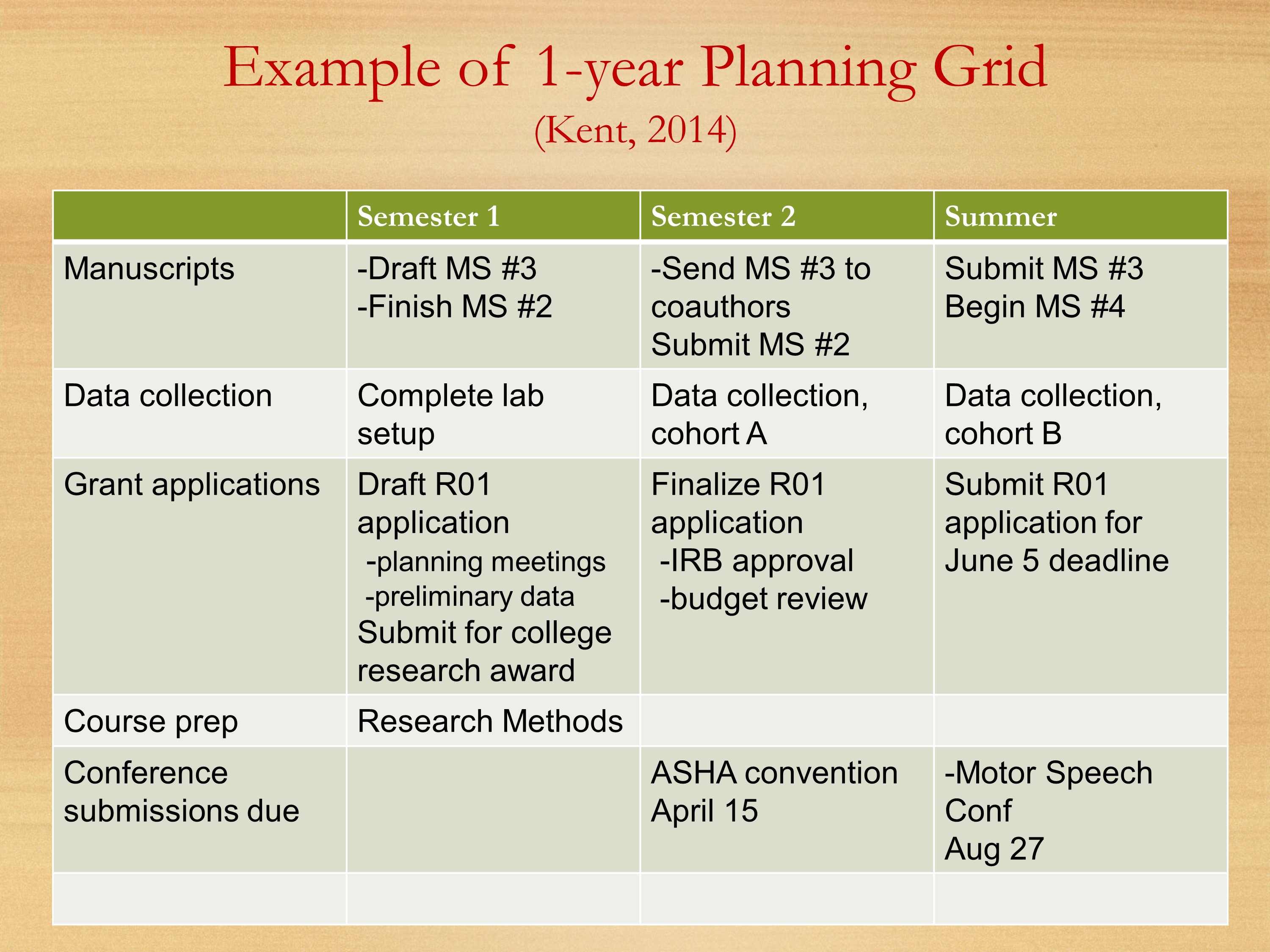

Here’s a grid that Ray Kent showed last year. We’re breaking it down by semester. Thinking about each of your semesters, what manuscripts you’re going to be working on, what data collection, your grant applications. Starting to get into some of those other buckets: course preparation, conference submissions.

We also need to include teaching and service.

You probably can’t see this very well. This is similar to that last slide Ray Kent had used last year.

I have my five year plan: what studies I want to accomplish, start thinking about breaking it down.

Then at the beginning of each semester, I fill in a grid like this. Where at the top, I have each of my buckets. I have my grant bucket, my writing bucket which is going to include publications. I also include doing article reviews in my writing bucket, because that’s my writing time. My teaching bucket, my research bucket. Then at the end, my service bucket.

At the beginning of the semester, I think about the big things I want to accomplish. I list those at the top. Then at the beginning of each month, I say, okay what are the things I’m going to accomplish this month, write those in. Then at the beginning of each week, I start looking at whether I’m dedicating any time to the things I said I was going to do that month. I start listing those out saying, this is the amount of time I’m going to spend on that. Of course, I have to take data on what I actually do, so I plug in how much time I’m spending on each of the tasks. Then I graph it, because that’s rewarding to see how much time you’re spending on things, and I get a little side-tracked sometimes.

Think about a system that will help you keep on track, to make sure you’re meeting the goals that you want to meet in terms of your research. But also getting the other things done that you need to get done in terms of teaching and service.

Discussion and Questions

Compiled from comments made during the Pathways 2014 and 2015 conferences. (Video unavailable.)

Building Flexibility into Your Five-Year Plan Comments by Ray Kent, University of Wisconsin-Madison

The five-year plan is not a contract. It’s a map or a compass. A general set of directions to help you plan ahead. It’s not even a contract with yourself, because it will inevitably be revised in some ways.

Sometimes cool things land in your lap. Very often it turns out that through serendipity or whatever else, you find opportunities that are very enticing. Some of those can be path to an entirely new line of research. Some of them can be a huge distraction and a waste of time. It’s a really cool part of science that new things come along. If we put on blinders and say, “I’m committed to my research plan,” and we don’t look to the left or the right, we’re really robbing ourselves of much of the richness of the scientific life. Science is full of surprises, and sometimes those surprises are going to appear as research projects. The problem is you don’t want to redirect all your time and resources to those until you’re really sure they are going to pay off. I personally believe, some of those high risk but really appealing projects are things you can nurse along. You can devote some time and build some collaborations – far enough to determine how realistic and viable they are. That’s important because those things can be the core of your next research program.

It’s very easy to get overcommitted. We all know people who always say “yes”—and we know those people, and they are often disappointing because they can’t get things done. It’s important to have new directions, but limit them. Don’t say, “I’m going to have 12 new directions this year.” Maybe one or two. Weigh them carefully. Talk about them with other people to get a judgment about how difficult it might be to implement them. It enriches science: not only our knowledge, but the way we acquire new knowledge. A psychologist, George Miller—this is the guy with the magic number 7 +- 2—when we interviewed him years ago at Boystown, he said, “My conviction is that everybody should be able to learn a new area of study within three months.” That’s what he thought for a scientist was a goal.

The idea is that you can learn new things. And that’s very important because when you think of it in terms of a 30-year career, how likely is it that the project that you’re undertaking at age 28 is the same project you’ll be working on at age 68? Not very likely. You’re going to be reinventing yourself as a scientist. And reinventing yourself is one of the most important things you can do, because otherwise you’re going to be dead wood. Some projects aren’t worth carrying beyond five or ten years. They have an expiration date.

Building Risk into Your Five-Year Plan Comments by Ray Kent, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Your doctoral study should generally be low-risk research. As you move into a postdoctoral fellowship, think about having two studies—one low-risk, one high-risk with a potential for high impact. At this time you can begin to play the risk factor a little bit differently.

When you are tenure-track you can have a mix of significance with low-risk and high-risk studies. And when you are tenured, then you can go for high risk, clinical trials, and collaborations. Because you have established your independence, so you do not need to worry about losing your visibility. You can be recognized as a legitimate member of the team.

As you plan your career, you should take risk into account. Just as you manage your money taking risk into account, we should manage our careers taking risk into account. I have met people who did not really think about that, and they embarked on some very risky procedures and wasted a lot of time and resources with very little to show for it. For example, don’t put everything into an untested technology basket. You want to be using state of the art technology, but you want to be sure it is going to give you what you need.

Other Formats and Uses of Your Research Plan Audience Comments

- If you do your job right with your job talk, there’s a lot of cross-pollination between your job talk and your research plan. Ideally your job talk tells your colleagues that this is the long-term plan that you have. And they shouldn’t be surprised when you submit a more detailed research plan. They should say, “okay this is very consistent with the job talk.” In my view, the job talk should be a crystal summary of the major aspects of that research program. Of course, much of the talk will be about a specific project or two—but it should always be embedded within the larger program. That helps the audience keep sight of the fact that you are looking at the program. You can say that this is one project that I’ve done, and I plan to do more of these, and this is how they are conceptually related. That’s a good example of why the research plan has multiple purposes – it can be a research statement, it can be the core of your job talk, it can be the nature of your elevator message, and it can be a version of your research plan for a K award application or R01 application or anything else of that nature.

- I think what’s useful is to actually draft your NIH biosketch. The new biosketch has a section called “contributions to science.” It’s really helpful to think about all your projects. It’s hard to start with a blank sheet of paper. But to have it in the format of a biosketch can be really helpful.

Avoiding Overcommitment Audience Comments

- One of the things that is amazing about planning is that if you put an estimate on the level of effort for each part of your plan, you’ll quickly find that you are living three or four lives. Some 300% of your time is spent. It’s helpful for those of us who might share my lack of ability to see constraints or limitations to reel it back and say, “I have a lot on my plate.” Which allows you to say no—which is not something we all do very well when it comes to those nice colleagues and those people you want to impress nationally and connect with. But it allows you to look at what’s planned and go, “I don’t know where I’d find the time to do that.” Which will hopefully help you stay on track.