Transferability In Qualitative Research

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

Transferability in qualitative research refers to the extent to which the findings of a study can be applied or transferred to other contexts, settings, or populations beyond the specific study sample.

Key Takeaways

- Transferability is an essential component of trustworthiness in qualitative research.

- It focuses on enabling readers to assess the applicability of findings to their own contexts.

- This involves researchers providing thick descriptions and readers engaging in critical interpretation.

- Transferability exists on a continuum, with the degree of transferability determined by the fittingness between contexts.

Unlike the concept of generalizability in quantitative research, which aims to extrapolate findings to a larger population, transferability recognizes the context-dependent nature of qualitative research and acknowledges that findings may not be universally applicable.

Guba (1981) argues that while generalizability is not a primary aim of qualitative research, transferability is achievable through “fittingness.”

This concept refers to the degree of similarity or “goodness of fit” between the research context and other potential settings where the findings might be applied.

Guba (1981) maintains that it is the reader, not solely the researcher, who bears the responsibility of gauging the “fittingness” of the research findings to their specific situation.

This emphasizes the role of the reader or the “knowledge user” in determining the relevance and transferability of the research to their specific circumstances.

To facilitate this process, researchers must equip readers with a thorough understanding of the study context through thick description.

This detailed account encompasses not only the research setting and participant characteristics, but also the intricate processes of data collection and analysis,

Strategies for Enhancing Transferability

Transferability determines the extent to which research findings can be applied to other contexts or with other subjects. It is a core component of trustworthiness , similar to the concept of generalizability in quantitative research.

1. Thick Description: Painting a Vivid Picture of the Context

Transferability in qualitative research refers to how well findings from one study context can be meaningfully applied to other settings or situations.

Unlike generalizability in quantitative research, which aims for universal applicability, transferability hinges on the “fittingness” between the original study context and the context to which the findings are being transferred.

Thick description serves as the primary tool for enabling transferability assessments.

In essence, it provides readers with the detailed contextual information they need to make informed judgments about this “fittingness.”

The aim is to create a compelling narrative that draws readers into the study context, allowing them to connect with the participants’ experiences and grasp the significance of the findings.

Instead of merely presenting bare-bones findings or themes, thick description involves providing a rich and detailed account of:

- Research Setting: This encompasses the physical, social, and cultural environment in which the study took place. It might include details about the community, the organization, or the specific location where data was collected.

- Participant Characteristics: Thick description extends beyond basic demographics to capture the diversity and complexity of the individuals involved in the study. This might include information about their backgrounds, experiences, perspectives, and roles within the research context.

- Data Collection and Analysis Procedures: A transparent and detailed account of the methods used to gather and analyze data is crucial for transferability. This includes describing the specific techniques employed (e.g., interviews, focus groups, observation), the rationale behind their selection, and how they were implemented in practice. Describing the analytic process, including the steps taken to identify themes, develop interpretations, and ensure rigor, allows readers to understand how the findings were generated and assess their potential applicability to other contexts.

When presenting thick description, avoiding jargon and overly abstract language in favor of clear, evocative language can make qualitative research more accessible and transferable to a wider audience.

This approach ensures that the rich contextual details are communicated effectively to readers from diverse backgrounds and disciplines.

2. Data Triangulation:

Relying on a single source makes a study more vulnerable to errors, such as biased questions or researcher influence.

By gathering data from diverse sources, researchers can illuminate different facets of the phenomenon, reducing the risk that their findings reflect only a partial or skewed perspective.

Using multiple data sources and collection methods can enhance the richness and comprehensiveness of the data, providing a more robust basis for considering transferability.

For instance, using a combination of observation field notes and interview transcripts to gain a richer perspective on the phenomenon being studied.

It’s crucial to note that triangulation does not necessarily imply seeking complete agreement across data sources. The goal is not to force a singular, unified interpretation but to acknowledge and explore the complexities and contradictions that may emerge.

By embracing these complexities, researchers can generate more nuanced and transferable insights.

For example, if one data source suggests a particular theme, while another reveals contradictory evidence, researchers should delve into these discrepancies, exploring the reasons behind the differences and considering how they might shape the overall interpretation of the findings.

3. The Reader’s Role: A Collaborative Process:

Transferability is not solely the researcher’s responsibility.

The onus also falls on the reader to evaluate the applicability of the research findings.

Readers must carefully consider the alignment between the study context and their own situation, factoring in aspects like participant demographics, cultural norms, and the specific phenomenon under investigation.

To support readers in this evaluation process, researchers should strive for clarity and transparency in their writing, avoiding jargon, overly abstract language, and technical terms that might hinder readers’ understanding.

The aim is to present the research in a way that is accessible and engaging for a wider audience, facilitating meaningful connections between the research context and potential applications.

One innovative approach to enhancing research accessibility and transferability is ethnodrama – a performance-based method that draws upon research data to create a dramatic script.

This approach goes beyond simply presenting research findings; it aims to capture the lived experiences of participants and convey them through dialogue, action, and storytelling.

By witnessing the experiences of others brought to life on stage, audiences can develop a deeper understanding of the research topic and potentially see connections to their own lives or situations.

Ethnodrama can be particularly impactful for communicating sensitive or complex issues, allowing audiences to connect with the research on an emotional level.

This method makes research more accessible to audiences beyond the academic community, bridging the gap between research and the public.

For example, when research findings are presented through dramatic performance, they often become more engaging and memorable for audiences, increasing the likelihood that the insights will be retained and potentially applied in other contexts.

Threats to Transferability in Qualitative Research

1. insufficient thick description:.

Thick description aims to create a rich and comprehensive picture of the research context, allowing readers to assess the similarities and differences between the study setting and their own situations.

A key threat to transferability is inadequate thick description of the research context, participant characteristics, and methodological procedures.

Without sufficient detail, readers lack the necessary information to judge the “fittingness” of the findings to their own situations.

This echoes Guba’s (1981) argument, as discussed in our previous conversation, that the reader bears the responsibility for evaluating transferability based on the researcher’s provision of rich contextual information.

2. Overemphasis on Thematic Emergence:

The over-reliance on thematic emergence as a marker of rigor in qualitative research .

While the identification of novel themes is valuable, an exclusive focus on emergence may neglect the importance of connecting findings to existing literature and theoretical frameworks.

This can hinder transferability by limiting the integration of findings into broader bodies of knowledge.

3. Inadequate Attention to Power Dynamics and Positionality:

Qualitative research is inherently influenced by the power dynamics and positionality of both the researcher and the participants.

Failure to acknowledge and account for these factors can limit transferability by obscuring the ways in which social contexts and individual perspectives shape the research process and its outcomes.

4. Lack of Reflexivity in Transcription:

Transcription, a critical stage in qualitative research, can also introduce threats to transferability.

The choices made during transcription, such as the level of detail included or the interpretation of non-verbal cues, are inherently subjective and can influence the analysis.

A lack of reflexivity in the transcription process can obscure these choices, making it difficult for readers to assess the potential influence on the findings and their applicability to other contexts.

5. Misuse of Member Checking:

While member checking can enhance credibility, its misuse can threaten transferability.

If member checking is treated as a validation tool aimed at achieving complete agreement with participants, it can stifle critical analysis and limit the potential for generating transferable insights.

6. Ignoring Negative Cases:

Failing to account for negative cases, those that do not fit the emerging patterns or themes, can lead to an overly simplistic representation of the phenomenon.

Ignoring negative cases can threaten transferability by obscuring the complexity and variability that might exist in other contexts.

7. Lack of Transparency in Data Analysis:

Transparency is important in qualitative data analysis for demonstrating rigor.

A lack of detail regarding the specific moves or strategies used in the analysis can hinder readers’ ability to assess the trustworthiness of the findings and their potential applicability to different settings.

How do I report transferability in my research?

Method section.

- Thorough Explanation of Sampling Strategies: Clearly articulate the rationale for your sampling choices, including inclusion and exclusion criteria. Describe the characteristics of your participant sample in detail (demographics, experiences, roles, etc.). This transparency enables readers to evaluate whether the sample is representative of the population of interest and to consider the potential generalizability of the findings.

- Detailed Documentation of Data Collection and Analysis: Describe the specific methods used to collect data (e.g., interviews, focus groups, observations), as well as the steps taken to ensure data quality. Provide a thorough account of your data analysis process, explaining how you coded, categorized, and interpreted the data. This level of detail enables readers to understand the rigor of your methods and to assess the potential for replication.

Results section

- Provide Rich, Descriptive Accounts of the Findings: Go beyond simply reporting themes or categories; instead, offer vivid and detailed descriptions of the patterns you observed. Use evocative language and illustrative quotes from participants to bring the findings to life, allowing readers to immerse themselves in the data and consider its potential relevance to other settings. This aligns with the concept of “thick descriptions” which are crucial for enhancing transferability.

- Highlight Similarities and Differences within the Sample: If your findings reveal variations in experiences or perspectives among participants, explore and discuss these differences. This exploration of nuances within the data can provide insights into the potential boundaries of transferability, helping readers to discern contexts where the findings might be more or less applicable.

- Relate Findings to Relevant Characteristics of the Sample: Connect the findings back to the specific characteristics of your sample (demographics, experiences, roles). For example, if you observe a particular pattern among participants with a certain level of experience, highlight this connection. This explicit linkage helps readers to assess the potential applicability of the findings to other groups with similar characteristics. This detailed reporting of the sample’s characteristics also strengthens transferability.

- Offer Tentative Insights about Potential Transferability: While avoiding definitive claims of generalizability, you can offer cautious insights about the potential relevance of your findings to other contexts. Use phrases like “These findings suggest that…” or “It is possible that…” to signal the tentative nature of these insights. For instance, you could write: “The strong emphasis on mentorship in this study suggests that similar programs in other healthcare settings might benefit from incorporating robust mentorship components.”

By thoughtfully presenting your results in a way that considers potential transferability, you invite readers to engage with the findings on a deeper level and to contemplate their broader implications.

Discussion section

The discussion section provides a prime opportunity to explicitly address the transferability of your findings and guide readers in considering their broader implications.

- Reiterate the Contextual Boundaries of the Study: Begin by reminding readers of the specific context in which your research was conducted, including any limitations or unique characteristics of the setting or sample. This transparency helps readers to assess the potential generalizability of the findings from the outset. As stated in, “Research meets this criterion when the findings fit into contexts outside the study situation that are determined by the degree of similarity or goodness of fit between the two contexts.”

- Compare and Contrast Findings with Existing Literature: Connect your findings to relevant theories and research from your field. Highlight areas of agreement or divergence, discussing how your findings support, challenge, or extend existing knowledge. This comparative analysis helps readers to situate your findings within a broader scholarly context and to consider their transferability in light of previous work.

- Discuss the Potential Implications for Other Contexts: Based on the insights gleaned from your data and its relationship to the existing literature, offer tentative suggestions about how your findings might apply to other settings, populations, or situations. Use cautious language and acknowledge the limitations of generalizability. For example, “While this study focused on a particular type of organization, the findings regarding the importance of clear communication channels may be relevant to other organizations facing similar challenges.”

- Identify Factors That Might Influence Transferability: Explicitly discuss factors that could either enhance or limit the transferability of your findings. For instance, cultural norms, organizational policies, or specific demographic characteristics of the sample might influence the applicability of the results to other contexts. Highlighting these factors guides readers in making informed judgments about transferability.

- Suggest Avenues for Future Research: Conclude by proposing directions for future research that could further explore the transferability of your findings. Encourage replication studies in different contexts or with different populations to test the boundaries of generalizability. This open invitation for further inquiry acknowledges the limitations of a single study and highlights the ongoing nature of knowledge construction.

By thoughtfully and critically addressing transferability in your discussion section, you empower readers to assess the relevance and applicability of your research beyond the immediate study context.

Reading List

- Anney, V. N. (2014). Ensuring the quality of the findings of qualitative research: Looking at trustworthiness criteria .

- Guba, E. G. (1981). Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries . Ectj , 29 (2), 75-91.

- Krefting, L. (1991). Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness . The American journal of occupational therapy , 45 (3), 214-222.

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1982). Establishing dependability and confirmability in naturalistic inquiry through an audit .

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation . New directions for program evaluation , 1986 (30), 73-84.

- Schwandt, T. A., Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2007). Judging interpretations: But is it rigorous? trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation . New directions for evaluation , 2007 (114).

- Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects . Education for information , 22 (2), 63-75.

- How it works

"Christmas Offer"

Terms & conditions.

As the Christmas season is upon us, we find ourselves reflecting on the past year and those who we have helped to shape their future. It’s been quite a year for us all! The end of the year brings no greater joy than the opportunity to express to you Christmas greetings and good wishes.

At this special time of year, Research Prospect brings joyful discount of 10% on all its services. May your Christmas and New Year be filled with joy.

We are looking back with appreciation for your loyalty and looking forward to moving into the New Year together.

"Claim this offer"

In unfamiliar and hard times, we have stuck by you. This Christmas, Research Prospect brings you all the joy with exciting discount of 10% on all its services.

Offer valid till 5-1-2024

We love being your partner in success. We know you have been working hard lately, take a break this holiday season to spend time with your loved ones while we make sure you succeed in your academics

Discount code: RP0996Y

Transferability in Qualitative Research

Published by Alvin Nicolas at September 21st, 2021 , Revised On October 10, 2023

What is Transferability?

Generally speaking, the term ‘transferability’ is used for something transferable or exchangeable. In research, however, the term is used for a very specific concept. That concept is better known as reliability . So, if it’s popularly known as reliability, why call it transferability?

Lincoln and Guba (1985) suggested a couple of terms that are better suited than reliability is to represent what it represents (as will be discussed below). One of those terms is transferability.

It will be assumed in the later paragraphs, therefore, that while reliability is being discussed, it’s also a discussion of transferability and vice versa. They are both the same thing.

Did you know: Reliability in research goes by many other names too, such as ‘credibility’, ‘neutrality’, ‘confirmability’, ‘dependability’, ‘consistency’, ‘applicability’, and, in particular, ‘dependability’.

Reliability in Research – Definition

Reliability is an important principle in two main stages of research, data collection and findings . The term is generally applied to data collection tools i.e., whether they are reliable or not.

What this means is that whether a tool—suppose a questionnaire—will yield the same results if applied under different settings, circumstances, to a different sample, etc.

Reliability is, therefore, a measure of a test’s or tool’s consistency.

That is the case for what it means to have a reliable tool or instrument. But what about reliable results, or reliable scores?

Reliable findings imply that no matter which instrument or tool is used to measure a certain thing, the results that the tool will yield will remain the same. Again, this is only possible when the measuring tool is reliable, to begin with.

In yet simpler terms, reliability refers to reaching to same conclusions consistently or repeatedly.

Key takeaway: It’s safe to assume, therefore, that reliable findings/scores and reliable measuring tools are two sides of the same coin.

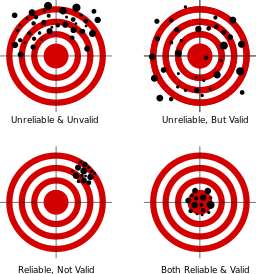

The following figure very effectively demonstrates what reliability is (about validity, as will be discussed later):

Reliability in Qualitative Research

When it comes to qualitative research , things like tests are commonly used. They can be in the form of pre-and post-tests that are administered on a sample, to observe the effects of something before and after exposure. Similarly, other qualitative tools like plotting graphs for the gathered data on test scores might be used as well.

Whichever qualitative method or tool is used, it has to be reliable.

Reliable Tests

Mostly, in research, tests are conducted in the form of questionnaires, surveys, etc. to gather information in the data collection stage. Those tests must remain reliable. In other words, if the same test is given to the same student or matches students on two different occasions, the test should yield similar results.

Test reliability means a test yields the same scores no matter how many times it’s administered, even if the test format is changed. Performance in a test might be affected by factors besides the abilities the test aims to measure (further discussed below).

Important to remember: Examination of reliability helps researchers tell apart the factors contributing most to a certain score, from the ones that have little to no effect.

Importance of Reliability in Qualitative Research

Researchers must obtain consistent results throughout the research process, no matter the type of instrument being used for data collection. However, reliability is more important than merely providing consistent results or scores throughout the process. It’s also important because of two other reasons:

1. First of all, reliability provides a measure of the extent to which a test-takers (any participant from the research sample, for instance) score reflects random/systematic measurement error. Observed Score = True Score + Error

Random error is an error that occurs due to random reasons and affects the results. Random factors include environmental factors, weather conditions, personal and/or psychological problems experienced by the researcher, and so on. Such errors affect results differently.

Systematic error is an error in a system. It affects the results in the same way. Such errors mostly include a fault in a measuring instrument; an incorrect marking scheme, etc.

The observed score is the total score that a test taker, for instance, gains on a test.

A true score is a score that is obtained, based on one’s knowledge.

Error: is the random or systematic error.

As the above formula shows, it is only when an error is accounted for that a researcher can tell what the actual, true score is. Once the error has been removed, the testing measure or tool can be deemed reliable or not. If, for instance, even after removal of the error, the observed scores are not obtained consistently, it means the test/tool is not reliable.

Key point: It’s easy to guess what ‘scores’ mean when it comes to quantitative research. They can be scores obtained from tests or some other statistical procedure. But what about scores in qualitative research? Even in qualitative research, quantitative methods might still be used, for instance, in the sampling and/or data interpretation stages.

2. The second reason to be concerned with reliability is that it is a precursor to test validity. That is, if scores can’t be assigned consistently, it is impossible to conclude that the scores accurately measure the domain they’re supposed to measure (validity).

Here, validity refers to the extent to which the inferences made from a test are justified and accurate. In other words, if a certain test/tool measures what it’s supposed to measure, it’s said to be valid . However, formally assessing the validity of specific use of a test/tool can be a difficult and time-consuming process.

Therefore, reliability analysis is often viewed as the initial step in the validation process. If the test/tool is unreliable, research won’t need to spend the time investigating whether it is valid; it won’t be. Contrarily, if the test has adequate reliability, a validation study would be worthwhile.

The key point to remember: Validity may be a sufficient but not necessary condition for reliability. However, reliability is an important condition for validity.

3. Quantitative research assumes the possibility of replication; if the same methods are used with the same sample, then the results should be the same. Typically, quantitative methods require a degree of control. This distorts the natural occurrence of phenomena.

Indeed, the premises of natural sciences include the uniqueness of situations, such that the study cannot be replicated – that is their strength rather than their weakness. However, this is not to say that qualitative research need not strive for replication in generating, refining, comparing, and validating constructs.

Therefore, just as replication and generalization of results are important in quantitative research, it might be just as important in certain types of qualitative researches, too. And hence, reliability is important in these kinds of studies also.

Types of Reliability in Qualitative Research

Now that the definition and importance of reliability have been established, it’s time to look at the multiple types of reliability that exist in research.

- Test takers’/participants’/respondents’ reliability

The test taker can be an individual from the sample, a student on whom the test is administered, a respondent of a questionnaire, or a participant of a survey. Naturally, all such individuals are human. They are therefore prone to experience stress, fatigue, anxiety, and other psychological and/or physiological factors. These factors might interfere and directly influence how these people perform on a test, survey, questionnaire, etc.

Also included in this category are such factors as a test-taker’s “test-wiseness” or strategies for efficient test-taking (Mousavi, 2002, p. 804).

- Rater reliability

This is further divided into two types:

- Inter-rater reliability: This implies whether two or more two raters, who are marking a test, questionnaire, etc., are reliable or not. It’s a measure of consistency between different raters’ ratings. For instance, if two or more than two of the raters/researchers come to the same score for a certain train in a psychological test, inter-rater reliability withholds.

It’s reliability within different raters.

- Intra-rater reliability: This implies whether or not the rater—the person who rates or ‘grades’ a certain test, summarises the scores of a questionnaire, etc.—is reliable or not. Are they under stress? Did they start rating after something bad happened to them? Are they qualified enough? Such factors can affect how a test or measuring tool is marked and in turn, may affect the results.

It’s reliability within the same rater.

- Item reliability: This is a measure of reliability used to evaluate the degree to which different test items that test the same construct produce similar results. This is because the test items may not be reliable. The items, for instance, maybe too easy or too difficult. Furthermore, they may not discriminate sufficiently between different members of the same sample of a population.

- Internal consistency reliability: As the name implies, this form of reliability is related to the format of a test, questionnaire, survey, etc. If different parts of a single test instrument led to different conclusions about the same thing, the test instrument’s internal consistency is low. This means the extent to which test questions measure the same skills or traits and the extent to which they’re related to one another is low.

- Test administrator reliability: There is reliability related to the test taker, test rater as well as test administration. Was the administration poorly managed in which the questionnaire or survey was conducted? Was there a lack of time to answer all the questions in the questionnaire? Did the questionnaires fall short of the total number of participants? Was there a problem with the photocopying of the same questionnaire?

All such factors directly influence test administrator reliability. If they’re mismanaged, this reliability will be reduced and vice versa.

- Test reliability: The rest itself can have some kind of error in it that can lower its reliability. For instance, in some researches, if the questionnaires given to the sample are too long, respondents might grow weary and not respond properly near the end, or not all at. Similarly, if the test is too complicated, respondents might ask others for help and copy off their answers to ignore the hassle of first understanding the question then comes up with an answer. Such factors lower a test’s reliability. This form of reliability is often overlooked in research, too.

How is Reliability Measured?

There are different methods of ensuring that the test, questionnaire, survey, or whichever other data collection tool is used, is very reliable. The methods depend on a couple of things, mainly the type of research, its objectives, sample type and so on.

However, the most common methods to determine and measure the reliability of a test or measuring tool are listed below. It should be noted that these are the general, most commonly used methods. There are variations to these methods themselves.

1. Test-retest reliability: This is a measure of reliability obtained by administering the same test twice over some time to a group of individuals. The scores obtained in the two tests can then be correlated to evaluate the test for stability over time.

This method is used to assess the consistency of a measuring instrument or test from one time to another; to determine if the score generalizes across time. The same test form is given twice and the scores are correlated to yield a coefficient of stability. High test-retest reliability tells us that examinees would probably get similar scores if tested at different times. The interval between test administrations is important—practice effects/learning effects.

2. Parallel or alternate form reliability : This is a measure of reliability obtained when research creates two forms of the same test by varying the items slightly. Reliability is stated as a correlation between scores of tests 1 and 2.

This method is used to assess the consistency of the results of two tests constructed in the same way from the same content domain; to determine whether scores will generalize across different sets of items or tasks. The two forms of the test are correlated to yield a coefficient of equivalence.

3. Internal consistency reliability: This method involves ensuring that the different parts within the same test or instrument measure the same thing, consistently. For example, a psychological test having two sections should be consistent in what it claims to measure, for instance, personal well-being. The first section could identify it via some questions, while the second section could include narrating a personal account.

4. Rater Reliability

- Inter-rater reliability : The reliability could be improved by making sure that there are no personal differences between the different rates, for instance, or that they are on the same page about their tasks and responsibilities.

- Intra-rater reliability: This reliability can be improved by ensuring, for instance, that the rater is not forced to rate a certain test after he/she went through something traumatic or is ill.

5. Item reliability: This reliability type will increase if the items or questions in a questionnaire, for instance, are different between different respondents; are easily understood by the respondents; aren’t too lengthy and so on.

Other Strategies to Improve Reliability of a Research Tool

To ensure their data collection test, tool or instrument is reliable, a research can:

- Objectively score tests by creating:

- Better questions

- Lengthening the test (but not too much)

- Manage item difficulty

- Manage item reliability

- Subjectively score tests by:

- Training the scorers/themselves

- Using a reasonable rating scale or techniques etc

- Both objectively and subjectively minimizing the bias by avoiding/promoting:

- To SEE the respondent in their image.

- To seek answers that support preconceived notions.

- Misperceptions (on the part of the interviewer) of what the respondent is saying.

- Misunderstandings (on the part of the respondent) of what is being asked.

Criteria for Reliability in Qualitative Research

In qualitative methodologies, reliability includes fidelity (faithfulness) to real life, context- and situation-specificity, authenticity, comprehensiveness, detail, honesty, depth of response, and meaningfulness to the respondents.

Denzin and Lincoln (1994) suggest that reliability as replicability in qualitative research can be addressed in several ways:

- Stability of observations: whether the researcher would have made the same observations and interpretations if observations had been done at a different time or in a different place.

- Inter-rater reliability: whether another observer with the same theoretical framework and observing the same phenomena would have interpreted them in the same way.

Conclusion

Reliability refers to the extent to which scores obtained on a specific form of a test, measuring tool or instrument can be generalized to scores obtained on other forms of the test or tool, administered at other times, or possibly scored by some other rater(s).

It’s a very important concept—for multiple reasons—to be considered during the data collection and interpretation stages of research. It’s also called transferability (of results) in qualitative research /

There are various types of reliability in research, each with its own dynamics. Certain criteria have to be met for a test or instrument to be reliable. There are many methods and strategies researchers can use to improve both the overall reliability as well as a specific type of reliability of their data collection tool.

Frequently Asked Questions

Transferability refers to the ability of knowledge, skills, or concepts learned in one context or situation to be applied effectively in a different context or situation, showcasing adaptability and practical utility beyond their original setting.

You May Also Like

Confidence intervals tell us how confident we are in our results. It’s a range of values, bounded above, and below the statistical mean, that is likely to be where our true value lies.

This comprehensive guide introduces what median is, how it’s calculated and represented and its importance, along with some simple examples.

A statistical measurement of the dispersion between values in a data collection is a variance. The symbol that is frequently used to represent variation is σ2.

As Featured On

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

Splash Sol LLC

- How It Works

Research Design Review

A discussion of qualitative & quantitative research design, sample size in qualitative research & the risk of relying on saturation.

Another potential problem arises when researchers rely solely on the concept of saturation to assess sample size when in the field. In grounded theory , theoretical saturation

“refers to the point at which gathering more data about a theoretical category reveals no new properties nor yields any further theoretical insights about the emerging grounded theory.” (Charmaz, 2014, p. 345)

In the broader sense, Morse (1995) defines saturation as “‘data adequacy’ [or] collecting data until no new information is obtained” (p. 147).

Reliance on the concept of saturation presents two overarching concerns: 1) As discussed in two earlier articles in Research Design Review – Beyond Saturation: Using Data Quality Indicators to Determine the Number of Focus Groups to Conduct and Designing a Quality In-depth Interview Study: How Many Interviews Are Enough? – the emphasis on saturation has the potential to obscure other important considerations in qualitative research design such as data quality; and 2) Saturation as an assessment tool potentially leads the researcher to focus on the obvious “new information” obtained by each interview, group discussion, or observation rather than gaining a deeper sense of participants’ contextual meaning and more profound understanding of the research question. As Morse (1995) states,

“Richness of data is derived from detailed description, not the number of times something is stated…It is often the infrequent gem that puts other data into perspective, that becomes the central key to understanding the data and for developing the model. It is the implicit that is interesting.” (p. 148)

With this as a backdrop, a few 2019-2020 articles on saturation come to mind. In “A Simple Method to Assess and Report Thematic Saturation in Qualitative Research” (Guest, Namey, & Chen, 2020), the authors present a novel approach to assessing sample size in the in-depth interview method that can be applied during or after data collection. This approach is born from quantitative research design and indeed the authors reference concepts such as “power calculations,” p-values, and odds ratios. When used during data collection, the qualitative researcher applies the assessment tool by calculating the “saturation ratio,” i.e., the number of new themes derived from a specified “run” of interviews (e.g., two) divided by the “base” number of “unique themes,” i.e., themes identified at the initial stage of interviewing. Importantly, the rationale for this approach is lodged in the idea that “most novel information in a qualitative dataset is generated early in the process” (p. 6) and indeed “the most prevalent, high-level themes are identified very early on in data collection, within about six interviews” (p. 10).

This perspective on saturation assessment is balanced by two other recent articles – “To Saturate or Not to Saturate? Questioning Data Saturation as a Useful Concept for Thematic Analysis and Sample-size Rationales” (Braun & Clarke, 2019) and “The Changing Face of Qualitative Inquiry” (Morse, 2020). In these articles, the authors express similar viewpoints on at least two considerations pertaining to sample size and the use of saturation in qualitative research. The first has to do with the importance of meaning 1 and the idea that finding meaning requires the researcher to actively look for contextual understandings and to have good analytical skills. For Braun and Clarke, “meaning is not inherent or self-evident in data” but rather “meaning requires interpretation” (p. 10). In this way, themes do not simply pop up during data collection but rather are the result of actively conducting an analysis to construct an interpretation.

Morse talks about the importance of meaning from the perspective that saturation hampers meaningful insights by restricting the researcher’s exploration of “new data.” Instead of using “redundancy as an indication for broadening the sample, or wondering why this replication occurs,” the researcher stops collecting data leading to a “more shallow” analysis and “trivial” results (p. 5).

The second consideration related to saturation discussed in both the Braun and Clarke and Morse articles is the idea that sample size determination requires a nuanced approach, with careful attention given to many factors related to each project. For researchers using reflexive thematic analysis, Braun and Clarke mention 10 “intersecting aspects,” including “the breadth and focus of the research question,” population diversity, “scope and purpose of the project,” and “pragmatic constraints” (p. 11). In a similar manner, Morse includes on her list of eight “criteria” such items as “the complexity of the questions/phenomenon being studied,” “the scope of inquiry,” and “variation of participants” (p. 5).

The potential danger of relying on saturation to establish sample size in qualitative research is multifold. The articles discussed here, and the image above, highlight the underlying concern that a reliance on saturation: 1) ignores the purpose and unique attributes of qualitative research as well as the individuality of each study, along with a variety of quality considerations during data collection, which 2) misguides the researcher towards prioritizing manifest content over the pursuit of contextual understanding derived from latent, less obvious data, which 3) leads to superficial interpretations and 4) ultimately results in less useful research.

1 Sally Thorne (2020) shares this perspective on the importance of meaning in her discussion of pattern recognition in qualitative analysis – “…qualitative research is meant to add value to a field rather than simply reporting what we can detect about it that has the qualities of a pattern… it should clearly add to our body of understanding in some meaningful manner.” (p. 2)

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health . https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing Grounded Theory (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Guest, G., Namey, E., & Chen, M. (2020). A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLOS ONE , 15 (5), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232076

Morse, J. (2020). The changing face of qualitative inquiry. International Journal for Qualitative Methods , 19 , 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920909938

Morse, J. M. (2015). Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Health Research , 25 (9), 1212–1222. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Thorne, S. (2020). Beyond theming : Making qualitative studies matter. Nursing Inquiry , 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/nin.12343

Share this:

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Pingback: A TQF Approach to Sample Size | Research Design Review

- Pingback: Actively Conducting an Analysis to Construct an Interpretation | Research Design Review

Helpful information for researchers and students who opt to undertake qualitative study. I have learned much more from this information and I like qualitative research

Like Liked by 1 person

- Pingback: Qualitative Analysis: ‘Thick Meaning’ by Preserving Each Lived Experience | Research Design Review

Love the discussion!

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

This sample-to-population background frame is widely emphasized in research texts, while qualitative sampling and transferability are typically minimally examined. This may make other models of generalization appear unusual and perhaps questionable.

Transferability in qualitative research refers to the extent to which the findings of a study can be applied or transferred to other contexts, settings, or populations beyond the specific study sample. ... { line-height: 1.7; } #printfriendly #pf-title { font-size: 40px; } ...

So there was no uniform answer to the question and the ranges varied according to methodology. In fact, Shaw and Holland (2014) claim, sample size will largely depend on the method. (p. 87), "In truth," they write, "many decisions about sample size are made on the basis of resources, purpose of the research" among other factors. (p. 87).

Sample sizes in qualitative research are guided by data adequacy, so an effective sample size is less about numbers (n's) and more about the ability of data to provide a rich and nuanced account of the phenomenon studied. Ultimately, determining and justifying sample sizes for qualitative research cannot be detached from the study ...

Transferability is a key . component of q ualitative research, ... The determination of sample size in qualitative research introduces a unique and multifaceted challenge, setting it apart from ...

Instead, concepts such as transferability can be used to reflect on the potential relevance and implications of qualitative research to other contexts. 2 The concept of transferability was first introduced by Lincoln and Guba 3 as an evaluative criterion suitable for constructivist 4 qualitative research to replace the (post-)positivist 4 ...

Reliability in Qualitative Research. When it comes to qualitative research, things like tests are commonly used. They can be in the form of pre-and post-tests that are administered on a sample, to observe the effects of something before and after exposure.

Meta-analyses of the peer-reviewed research on sample sizes for qualitative data are also widely cited in the sample size estimation literature (Carlsen & Glenton, 2011; Marshall et al., 2013; Mason, 2010; Sobal, 2001; Thomson, 2011).

Qualitative and quantitative research designs require the researcher to think carefully about how and how many to sample within the population segment(s) of interest related to the research objectives. In doing so, the researcher considers demographic and cultural diversity, as well as other distinguishing characteristics (e.g., usage of a particular service or product) and pragmatic…

To bring this one home, let's answer the question we sought out to investigate: the sample size in qualitative research. Typically, sample sizes will range from 6-20, per segment. (So if you have 5 segments, 6 is your multiplier for the total number you'll need, so you would have a total sample size of 30.)