A Descriptive Study of COVID-19-Related Experiences and Perspectives of a National Sample of College Students in Spring 2020

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Public and Nonprofit Administration, School of Management, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, California. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Department of Psychology, Fordham University, New York, New York.

- PMID: 32593564

- PMCID: PMC7313499

- DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.009

Purpose: This is one of the first surveys of a USA-wide sample of full-time college students about their COVID-19-related experiences in spring 2020.

Methods: We surveyed 725 full-time college students aged 18-22 years recruited via Instagram promotions on April 25-30, 2020. We inquired about their COVID-19-related experiences and perspectives, documented opportunities for transmission, and assessed COVID-19's perceived impacts to date.

Results: Thirty-five percent of participants experienced any COVID-19-related symptoms from February to April 2020, but less than 5% of them got tested, and only 46% stayed home exclusively while experiencing symptoms. Almost all (95%) had sheltered in place/stayed primarily at home by late April 2020; 53% started sheltering in place before any state had an official stay-at-home order, and more than one-third started sheltering before any metropolitan area had an order. Participants were more stressed about COVID-19's health implications for their family and for American society than for themselves. Participants were open to continuing the restrictions in place in late April 2020 for an extended period of time to reduce pandemic spread.

Conclusions: There is substantial opportunity for improved public health responses to COVID-19 among college students, including for testing and contact tracing. In addition, because most participants restricted their behaviors before official stay-at-home orders went into effect, they may continue to restrict movement after stay-at-home orders are lifted, including when colleges reopen for in-person activities, if they decide it is not yet prudent to circulate freely. The public health, economic, and educational implications of COVID-19 are continuing to unfold; future studies must continue to monitor college student experiences and perspectives.

Keywords: COVID-19; College students; Epidemiology; Health behavior; Public health; USA.

Copyright © 2020 Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Attitude to Health*

- Coronavirus Infections / epidemiology*

- Coronavirus Infections / prevention & control

- Coronavirus Infections / psychology*

- Health Behavior

- Pandemics / prevention & control

- Pneumonia, Viral / epidemiology*

- Pneumonia, Viral / prevention & control

- Pneumonia, Viral / psychology*

- Students / psychology*

- Students / statistics & numerical data

- Surveys and Questionnaires

- United States / epidemiology

- Universities

- Young Adult

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

An Exploratory-Descriptive Study on the Impact of COVID-19 on Teaching and Learning: The Experiences of Student Nurses in the Rural-Based Historically Disadvantaged University of South Africa

Lufuno makhado , phd, ofhani p musekwa , ma, masane luvhengo , bpsych, tinotenda murwira , phd, rachel t lebese , phd, mercy t mulaudzi , phd, maphuti j chueng , mph.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Lufuno Makhado, Department of Public Health, University of Venda, 1 University Road, Thohoyandou, Limpopo 0950, South Africa. Email: [email protected]

Received 2021 Dec 1; Revised 2022 Mar 17; Accepted 2022 Mar 23; Collection date 2022 Jan-Dec.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages ( https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage ).

Covid-19 has disrupted normal working conditions as people were not allowed to assemble in one place. There is a limit that is placed on the number of people congregating in public areas, and these measures also affect the education system worldwide. The purpose of the study was to explore nursing students’ experiences in a historically disadvantaged rural-based university on the impact of Covid-19 on teaching and learning. The study employed an exploratory-descriptive qualitative design among nursing students who were purposively sampled to participate in the study. A qualitative self-administered open-ended online google form was used to collect data. Thematic analysis was employed for this study. All ethical measures were respected during this study. Interviews were conducted with 68 participants, including 12 undergraduate second-year students, 7 third-year students, and 49 fourth-year students. A total of 51 females and 17 males participated in this study. The study yielded several themes, including participants’ expression of their experiences related to teaching and learning during the national lockdown, participants’ views on the impact of COVID-19 on teaching and learning/research, and Participants suggested sustainable strategies to promote teaching and learning during the national lockdown. In conclusion, the role of preceptors in all clinical areas should be strengthened to improve clinical teaching and learning. The researchers recommend strengthening collaboration among university lecturers for sharing ideas and finding innovative solutions appropriate for handling any pandemic that threatens teaching and learning processes.

Keywords: COVID-19, experiences, impact, nursing students, rural-based historically disadvantaged university, South Africa, teaching and learning

What do we already know about this topic?

• Covid-19 disrupted the normal educational processes.

• The national COVID-19 lockdown negatively impacted access to teaching and learning, affordability, and reliability of the internet data for nursing education in specific areas

How does your research contribute to the field?

• This paper provides the teaching and learning experiences for nursing students at a historically disadvantaged University.

What are your research’s implications toward theory, practice, or policy?

• The University needs to put more resources and innovative strategies to facilitate effective online teaching and learning.

• The introduction of a new learning modality should be accompanied by a thorough orientation of both learners and lecturers to facilitate effective learning.

Introduction

Covid-19 has disrupted normal working conditions as people were not allowed to assemble in 1 place. There is a limit that is placed on the number of people congregating in public areas, and these measures also affect the education system worldwide. 1 Regular class attendance was disrupted, and educational systems had to come up with innovative alternative methods of teaching and learning in a bid to rescue the academic activities and calendar. 1 - 6 In response to the Covid-19 restriction, the South African Department of Higher Education had to implement policies and guidelines for the higher education institutions. This saw the Education system moving to online teaching and learning to free up institution capacities and access learners, teachers, and parents. 7 - 10 However, not all learners have equal access to digital devices and the internet, affecting how this interaction is achieved. 7 - 9 , 11 - 14 The move to online learning tested the institution of higher learning readiness to advance the use of technology in teaching and learning, which was imperative. 1 , 2 The move to online teaching and learning platforms introduced various perceptions, advantages and disadvantages and some difficulties among all stakeholders.

Online learning help to facilitate communication between academics, especially when contact is impossible; however, this view received differing receptions from all stakeholders. 15 - 19 As others portrayed negative attitudes toward online learning, others fully supported it. 16 These online learning features include whiteboards, chat rooms, quizzes, and discussion forums. 20 , 21 These features allow discussions between academics and students in pursuit of achieving their teaching and learning goals. 20 However, within the nursing sphere, nursing education was heavily impacted by the Pandemic and reduced contact between nursing students and facilitators. 22 - 24 Some of the issues found in other contexts outside South Africa were reduced mobility to the healthcare facilities for practice purposes, reduced number of nursing staff within the unit, electricity supply, reception and connectivity issues, and the ability to use the online learning platforms effectively. 22 - 24 The COVID-19 lockdown negatively impacts access to, affordability, and reliability of the internet for nursing education in certain areas. Furthermore, the national lockdown affected nursing education, which was characterized by intense contact learning classes and practical sessions requiring hands-on activities.

The nursing qualification is mainly based on the integration between theory and practice. This integration has been seen to suffer the blow of the COVID-19 Pandemic as rapid changes were effected to promote continuity and progression of studies. In response to the Covid-19 restrictions, the University of Venda also introduced online teaching and learning to save the academic year and achieve educational goals. Online teaching and learning platforms were strengthened, and more were introduced. These platforms included blackboard, Microsoft teams, Moodle, zoom, WhatsApp, to name a few. Given the speed and magnitude of change that COVID-19 Pandemic, many challenges had been verbalized concerning COVID-19 restrictions and the nationwide lockdown. Nursing students are also affected by these changes. Given the practical nature of their qualification, it was deemed necessary to explore their experiences and perceptions of the recent new normal. It is against this background that researchers conducted a study to explore the experiences of online teaching and learning by nursing undergraduate students.

The study employed an exploratory-descriptive qualitative design. This design offered the researchers a platform to understand nursing students’ experiences during the national COVID-19 lockdown. In addition, this design uses participants’ narratives to best articulate and understand the phenomenon of interest, especially when the issue is poorly understood. 25 , 26 Accordingly, this descriptive qualitative design was proper to understand students’ experiences regarding teaching and learning during the national lockdown. Furthermore, qualitative descriptive research “is designed to provide a picture of a situation as it naturally happens,” 27 which this study sought out.

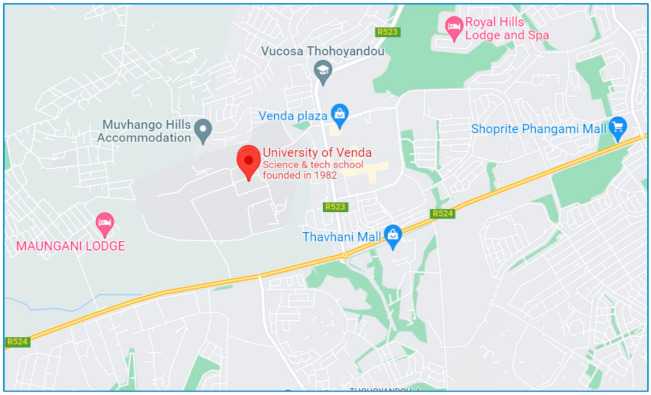

The study was conducted among nursing students at the University of Venda. The University of Venda is one of the 26 public universities in South Africa. It is mainly a historically disadvantaged institution (HDI) with 1 main campus based in Thohoyandou town and has 4 faculties schools, including Faculty of Health Sciences; Humanities, Social Science and Education; Management, Commerce and Law; and Science, Engineering and Agriculture. It has approximately 15 500 registered undergraduate and postgraduate students. The University of Venda is populated with mostly students from Limpopo and Mpumalanga. The majority of these students come from low to middle-class family backgrounds. In addition to this, there are geographical complexities as most come from remote and underdeveloped communities. Furthermore, the academic, administrative, and support staff of approximately 800 is employed at the University of Venda. 28 The map showing the study area is presented in Figure 1 .

Study setting.

Sampling and Participants

Purposive sampling was employed to select nursing students meeting inclusion criteria of (i) being a registered nursing student at the University of Venda, (ii) undergraduate students, (iii) both male and female nursing students participating in online learning, and (iv) willing to participate in the study voluntarily. About 68 undergraduate nursing students participated in the study. The participants were from the Department of Advanced Nursing Sciences, under the Faculty of Health Sciences. The sample size was determined by data saturation described by Mason, 29 attained at student number 23; however, further submissions were analyzed for the surety of saturation and trustworthiness of the study. Hence the total sample size was 68 undergraduate nursing students.

Data Collection

Data were collected from 25 March to 30 August 2020 through a qualitative open-ended online google form that was self-administered and sent via email, SMS, and WhatsApp media. Google form is a cost-effective method that can reach many respondents who are in different areas. 30 , 31 The online form was developed based on literature and was validated by experts (i.e., professional Nurses and Researchers). This method was chosen as an effective way of collecting in-depth information from a wide range of participants who cannot attend face-to-face semi-structured interviews, 31 given the COVID-19 restrictions. Furthermore, anonymity and confidentiality were ensured as the data collection method discourages potential biases associated with face-to-face interaction. The open-ended questions encourage students to open up and provide in-depth details about their experiences, views, and perceptions without interruptions. 32

The interview guide was composed of study details, demographic details, and 4 open-ended questions. The study focused on answering the following open-ended questions, What are your experiences regarding undergraduate learning (theoretical and practical) during the national lockdown? What are the prospects and challenges regarding measures put in place to promote learning in undergraduate nursing? What is the impact of COVID-19 on your undergraduate nursing learning and research ? And What are the possible applicable/favourable and sustainable strategies that can be utilized as a way forward to promote uninterrupted undergraduate nursing teaching and learning within the University? The study data collection tool was pretested and validated before data collection.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was done through thematic analysis, following familiarization, code generation, theme development, reviewing and defining the themes, and finally writing the study. 33 Thematic analysis was chosen for its systematic approach and procedures that are clearly described with yield rich descriptive analysis from raw data. Therefore, this inductive approach was followed, the research team (ML, MOP, MT, LM, LRT, and MMT) identified themes independently from the data obtained from open-ended questions. In addition, the data from open-ended questions ranged from a few texts to long paragraphs.

Further, these coded items were grouped into 4 main themes and 8 subthemes through consensus by the research team. To ensure credibility, the researchers coded the data independently before reaching a consensus. 34 Furthermore, dependability and confirmability were facilitated by providing detailed research methods and a clear audit trail. We enhanced credibility, dependability, reflexibility, confirmability, and applicability by encouraging interdisciplinary discussions between nursing, psychology, and public health. This prompted the research team members to analyze data through a wide range of disciplinary and professional lenses. Thus, this process allowed for triangulation of perspectives, enabling research team members from different cultural, academic, age and gender backgrounds to input meaningfully into the process and build empirical and conceptual generalizability.

This study was conducted in 2020 from July to September after the national lockdown in South Africa. The education system moved from face-to-face contact learning to online learning, a new experience for both academics and students. The study data was collected online, where participants responded to the semi-structured interview. A total of 68 participants were interviewed with the following categories: undergraduate second year 12; undergraduate third year 7; and undergraduate fourth year/honors 49. Among these participants, 51 were females, and 17 were males. The following Table 1 shows the demographic distribution of participants.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants.

Emerging Themes, Subthemes, and Categories

The data from all participants yielded 3 main themes, which are participants’ expression of their experiences related to teaching and learning during the national lockdown; participant’s views on the impact of COVID-19 on teaching; and learning/research, and participants suggested sustainable strategies to promote teaching and learning during the national lockdown. From the 3 main themes, 5 subthemes emerged, which were positive experiences of teaching and learning during lockdown; negative experiences of teaching and learning during lockdown; the negative impact of COVID-19 on teaching and learning, the negative impact of COVID-19 on teaching and learning; and participants suggested strategies to promote teaching and learning during the national lockdown. Table 2 shows the themes, sub-themes, and categories that had emerged from the data.

Themes, Sub-Themes, and Categories.

Theme 1: Participant’s Expression of their Experiences Related to Teaching and Learning During National Lockdown

Participants described their experiences related to teaching and learning during the lockdown and being negative and positive. However, from these descriptions, it has been identified that most of their experiences were negative with few positive experiences. Two sub-themes emerged from the central theme: Positive experiences of teaching and learning during the lockdown and Negative experiences of teaching and learning during the lockdown.

From this central theme, 1 participant said:

“lockdown affected us a lot like the idea of studying from home was new to us. We had to teach ourselves how to use the different software and system. The Pandemic did not give us time. It was difficult to use our cell phones as we did not have computers, and data was also a problem. Sometimes we lost connection during the lessons. This wasn’t easy. However, we have become more computer literate, and it now feels good” P34, F, 17 years.

Sub-theme 1.1: Negative Experiences of Teaching and Learning During Lockdown

Almost all the participants related negative teaching and learning experiences of being on national lockdown. These adverse experiences are attributed to the lack of preparation, as the COVID-19 restriction caught them off guard without prior arrangements. One of the participants said:

“It is challenging to study from home. The parents and siblings expect you to participate in the household chores fully, and they don’t understand if you spend your day watching the cell phone the think that you are chatting to your friends. There is also noise within the household and from the neighbours. Connectivity is also a problem, and data is expensive . . . ” P5, F, 17 years.

The following are the different categories that emerged from data: Difficult to concentrate when at home; Lack of materials to be used as reference; Poor functioning connectivity; Poor communication from lecturers and Uncertainty related to time to resume contact lessons.

Difficult to concentrate when at home

Most of the participants expressed having had trouble when attending classes from home. They related how their parents and siblings did not understand when they sometimes could not perform chores because they were attending class or reading. The family members felt that they were hiding behind the fact that classes were in session most of the time. Another factor that made attending classes from home was a noise within the household as younger children wanted to play, and the noise was uncontrollable; this also included irregular visitors. This is what participants said:

“It is challenging to attend classes from home. Some chores are done every day, and my siblings, including my mother, [who] want me to join and assist. This is not possible as in someday I have long classes from different academics” P40, F, 20 years.

“My neighbourhood is very noisy as my home is next to the tavern. If I want to have a successful class, I will go to my grandparents’ house, which is far. Besides the tavern, I also have little brothers and sisters who always want to play, and they can’t be quiet for a long time” P44, M, 20 years.

Lack of materials to be used as reference

The lack of materials to be used as reference was a problem as participants could not refer their work to different sources because they could not access the library. Searching the internet was almost impossible because of unavailable data. This is compounded by the fact that most students are from low-income families who cannot afford basic living requirements.

One participant said:

“my parents are not working, and their source of income is from my grandparents, it is impossible to buy data for me every time, and this data gets finished so quickly, one cannot manage, there were times that I would go and sit outside KFC to access their free Wi-Fi, which is also difficult as I need to pay for the taxi” P47, M, 19 years.

Poor functioning connectivity

Most of the participants expressed how internet connectivity consistently disrupted teaching and learning. This was said to be worse because there was always load shading. It was said that sometimes other people would connect who are in a different area and others could not connect. This was said to interfere with teaching and learning and make another group ahead of other groups. Some academics also echoed this problem and indicated that load shading inhibited their scheduled time because they resided in different places. Load shedding was not occurring simultaneously in different areas, making it difficult for them to have an entire class, and repeating classes was time-consuming and tiresome. One participant verbalized this:

“ load shading of electricity by Eskom is a major problem. The lecturer will set up a class for a specific time, and the class will never take place in other areas as the load shedding schedule is different for different areas. You will find that the class did take place for students in other areas and not take place in some areas which makes us not to be on the same level and catch up very difficult” P14, F, 18 years.

Poor communication from lecturers

Poor communication was said to be one major problem experienced by students. The students expressed their frustrations related to poor communication from academics. They noted that communication was often late, which prevented good planning from their side. The activities were also not to be well-coordinated as there would often be clashes in class attendance or writing of tests. One academic confirmed this by saying that conflicts were often experienced as academics did not follow a well-structured timetable.

One second-year student said:

“the academics communicate at the last minute, making it difficult to plan our work. There were clashes which show that there was also no communication between the academics. You end up not knowing which class you need to attend. Some academics would schedule classes in the evening, leaving us with no time to read” P15, M, 17 years.

Uncertainty related to time to resume contact lessons

Participants expressed how they felt when they could not tell when they were going to resume contact lessons. This was mainly expressed by students who experienced connectivity problems. They explained how they would often wait for the University’s announcement about the resumption of normal academic activities. The student felt that the extended lockdown interfered with their educational activities leading to a high failure rate.

This is what 1 participant said:

“we would patiently follow the news about the resumption of normal academic activities, and this could not come. You know sometimes you need somebody to hold your hand and explain things that are not well understood” P40, F, 20 years

Sub-theme 1.2 Positive Impact of COVID-19 on Teaching and Learning

Data revealed that a few participants viewed online teaching and learning as having a positive impact. They explained how the new mode of teaching and learning is exciting as they learn at their own pace and learn new things every day. The category that emerged from this sub-theme is the following: Change in the way learning occurs.

Change in the way that learning takes place

Participants expressed their positive views on how learning is taking place. It was explained that the best thing was that the lessons were recorded, and they could replay to enhance understanding. It was exciting because they were continuously exposed to something they were not expecting. Hands-on the digital world was said to be the most exciting part. One of the participants said:

“We learn new ways of getting information and manoeuvring the exciting software. Remember we are in the 4 th industrial revolution, and now we are learning the same way as students from the well-resourced institution” P14, F, 17 years .

Theme 2: Participants’ Views on the Impact of COVID-19 on Teaching and Learning/Research

The impact of COVID-19 on teaching and learning was said to be both negative and positive. The negative implications ranged from lagging work, especially in courses where the student is expected to complete specified hours of clinical work by accreditation bodies. There were also concerns from the students who were conducting research, and the concerns were mainly about their inability to collect data and consequently extension of the academic year.

One participant verbalized this:

“ I planned to finish my studies this year so that I can start working and help my parents financially next year, but I don’t see this happening as I’m behind with my practical hours as required by the South African Nursing Council. I’m very worried about the thought of extending my academic year, and this year was a disaster . . .” P12, F, 19 years.

From this central theme, the following sub-categories emerged: Negative impact of COVID-19 on teaching and learning and Positive impact of COVID-19 on teaching and learning.

Subtheme 2.1: Negative Impact of COVID-19 on Teaching and Learning

Most of the nursing students described the negative impact as detrimental to their mental health. They felt that they were always scared of contracting the disease while on practicals and feared losing the academic work. Their theoretical work progress is plodding, which is also compounded by poor connectivity. This is what the 19-year-old female 4 th -year student said:

“I think most of us are frustrated because we are unsure of the future. The infection rates are going up every day, which means that we will not go to campus very soon. The pace at which we are being taught is also very slow, and we rarely go for practicals which are also an important component of our learning” P12, F, 19 years.

Academic work lagging

The students’ academic work was described as lagging. This is said to be related to poor connectivity and clashes in the scheduling of classes as the academics are no longer following the regular timetable like when we are on campus. The students also said that the lack of laptops was also a problem as they always use their cell phones to connect, and always difficult to read the fine print from the cell phone. Some students expressed how difficult it is to understand what they are being taught when the lecturer is not there to explain the problem further. This is what 1 participant said:

“With theory, it’s tough for me to understand everything as I prefer being taught in class and being able to ask questions . . .” P31, F, 22 years.

Difficult to collect information due to restrictions

During the national lockdown, a participant described how complex collecting data for their research projects was. The lockdown regulation prohibited meetings and movement, which made them suspend data collection for their fourth-year research projects. Participants’ description of problems related to data collection was also compounded by their fear of contracting the disease during data collection.

This is what some participants said.

“Anxiety has become my friend. I always think of the possibility of being infected when collecting data as such. I felt uncomfortable being around other people” P10, F, 23 years.

“It is hard and depressing. Especially because I am disadvantaged financially and on the issue of network.” P50, F, 22 years.

Missed practical hours

All participants were nursing students whose teaching and learning involve the integration of theory and practice. The practical component forms an integral part of their training, and to qualify as a nurse, they are required to achieve a certain number of clinical hours. This was said to be impossible to achieve because of restrictions. Sometimes they could not go to the clinical areas because the students were not provided with protective clothing, including the restrictions on the movement of people. The approved clinical sites were also said to be away from their homes, which made access to the clinical sites impossible. These are some of the quotes from the participants.

“It is difficult to cover practical work more than theoretical work online” P19, F, 23 years.

“I had been frustrated, scared and hopeless as the degree is mainly practical” P1, M, 24 years.

“We lost many hours on practicals due to Covid-19, our research is behind because we haven’t done data collection due to social distancing, on the theory we were unable to learn more from the lectures due to Covid-19.” P44, F, 20 years

“It was difficult to meet our learning outcomes theoretically and practically.” P61, M, 22 years.

“Practically, we face the challenge of not having enough personal protective equipment (PPEs).” P21, M, 24 years.

No contact with lecturers

Participants explained the difficulty they encountered when they could not have physical contact with their lecturers. Some of the participants describe how uncomfortable they were to discuss specific issues in the presence of other students during online learning. They felt that this exposed them to their poor grasp of the content. Meanwhile, they booked an appointment during the normal learning period and discussed their problems alone with their teachers.

This is what 1 student said,

“It is challenging to ask the question when being taught online. The other students always complain that you are wasting time as the lesson then move very slow when the lecturer explains, their grumbling makes you uncomfortable and becomes hesitant when one wants to ask a question” P32, F, 19 years.

Subtheme 2.2: Positive Impact of COVID-19 on Teaching and Learning

Besides the negative impact described by the participant, positive responses have also described the impact of COVID-19 national lockdown on teaching and learning. The subtheme that came out of the data was changed in the way of learning.

Change in the way learning takes place

Participants expressed excitement concerning the new way of learning, which was in line with the fourth industrial revolution. They said that using technology puts them in a good position for the future. They said that the future would be digitalized, and this form of learning does prepare them for the future. One participant said:

“Is that, with technology, nothing can stop us from securing our future.” P23, F, 21 years.

Theme 3: Participants Suggested Sustainable Strategies to Promote Teaching and Learning During the National Lockdown

Participants suggested different strategies to solve the problems they are experiencing about teaching and learning during the national lockdown. Few of the participants felt that there is a need to establish a user-friendly software or system that is less costly. Almost all the participants also suggested the supply of necessary tools. The participants also felt that access to the campus could allow students in areas without connectivity and those struggling. From this central theme, the following sub-themes emerged: Suggested strategies.

Subtheme 3.1: Suggested Strategies

Participants suggested different which are the following: Establishment of better user-friendly software and systems; Conduction of regular workshops; Provide students with equipment to use timeously; Allow student to access the campus and Help struggling students.

Establishment of better user-friendly software and systems

Participants suggested that the University could benchmark the different user-friendly software available. This was said to help all the students, especially those who are not computer literate. The University was also advised to use the information system department on campus to check if they cannot develop a much cheaper product that can be easily accessible on the university website without demanding data. These are some of the quotations from the participants:

“You know it is so difficult to use some of the programs they are using. With the zoom, you are often timed out before you can even ask questions . . . . .” P43, M, 21 years.

“We have a department doing programming at this University. Why can’t these people develop some systems built in to reduce costs? You know most of us are from poor backgrounds . . .” P30, F, 19 years.

Conduction of regular workshops

It was further suggested that the students need a regular workshop on using these programs. This was prompted by the fact that there is much information on these programs if teaching and learning are expected to be helpful. One participant said:

“We need a lot of orientation and follow-up workshops because these programs have a lot of features that one needs to be conversant with to use it successfully. Like how to get notices, upload, notes and many more” P13, M, 20 years.

Provide students with equipment to use timeously

Participants explained how difficult it was for them to get the necessary equipment for online learning. Before receiving their laptops, they relied on their cell phones for connection. This was said to be even worse for students who did not have smartphones and living in areas with bad connectivity. This is what some of the participants said:

“It took us a long time to get the laptops and data to assist us with our learning. It was so difficult because I don’t have a smartphone, and I relied on my friend who could send me a message about what had been done. [it is] so difficult.” P44, F, 20 years.

“The laptops arrived very late when we had gone back to campus. Only God knows if we will make it this year . . .” P2, F, 18 years.

Allow students to access the campus

Data revealed that some participants felt that the University could have arranged for some needy students to remain on campus. This was said because some live in very remote areas without connection, and they could not connect. It was also expensive to travel to their friend’s home to attend lessons. One of the participants indicated:

“I think they should have made some arrangements for a few students who could not connect completely because they really suffered and were anxious . . .” P5, F, 20 years.

Help struggling students

Data revealed that participants felt that online learning did not provide an excellent platform for struggling students as immediate follow-up after a lesson is often impossible. This was frustrating as the lecturer sometimes is in a hurry against time and an element of not being free to discuss issues that affect individuals. One of the participants said.

“during contact lessons ill often go back with the lecturer to the office and discuss issues that I’m not satisfied with along the way, and the discussions always helped me catch up with the other learners.” P47, F, 21 years.

The study results indicate that most of the student nurses’ experience was negative toward online learning. They were not prepared and were not given orientation that could enable them to work independently. These negative attitudes were also identified in different studies where both educators and students had negative attitudes toward online learning, which was related to access to the internet and their poorly equipped knowledge related to the use of technology. 35 - 37 These negative attitudes were also affirmed by Abbasi et al. 38 in a cross-sectional study among medical students. More than half of the respondents indicated that they preferred face-to-face teaching. Adapting to new teaching pedagogy of online learning is experienced differently by different age groups and subjects, with older people being slow to adapt than the younger generation. This could also influence their attitudes toward the new type of teaching and learning. 39 However, online learning was identified as a vehicle through which learners are empowered to participate at their own time and reinforce self-directed. Educators’ collaboration is also enhanced as a coalition contributes to the larger product. 39 - 41 A couple of studies revealed positive reports related to online learning among medical students who felt that online learning improved their access as it is flexible with less administration. 5 , 40 - 44

Besides the negative attitude related to online learning, the nursing students verbalized the frustrations they face when studying from home. The family does not understand when they do not join in performing household chores. Similar findings were identified in the study among students from the rural villages of Bhutan, where their illiterate farming parents wanted them to help in the fields and tend cattle. Some of the students were made to care for ailing relative to postponing examination. 39 The different family backgrounds and literacy levels impact the effectiveness of online learning as the unconducive home environment could cause psychological and emotional stress to students and hamper learning.

This study was conducted among rural base university nursing students. Most of them come from rural areas with poor or no internet connectivity, compounded by the low socio-economic status to enable them to buy enough data to connect. The problem related to connectivity to the internet and access to digital gadgets was also highlighted by other studies as an impediment to effective online learning. 39 , 40 data revealed that the nursing students expressed that they preferred being given laptops, making it easier to connect and learn. This is disputed by different studies, which show that some students, especially medical students, prefer using their mobile gadgets rather than their laptops. 38 , 45 , 46 , 47

Failure to use information and communication technology is also regarded as 1 factor that prevents effective online learning. The nursing students involved in the study indicated the need for orientation and continuous workshops for both the students and educators. This was emphasized by Pokhrel and Chhetri, 39 who indicated that online teaching and learning also depend on information and communication technology expertise for both educators and learners. Poor technical skills could be a factor that contributes to a drop in pass rate during lack of contact learning and consultation. Assessments are carried out by trial and error online, and expertise is poor among the learners and educators. 38

Despite the failure to connect and inability to use technology, online learning was said to interfere with attendance of clinical practice due to restrictions and social distancing regulations. Mukhtar et al. 40 also identified online learning as ineffective teaching psychomotor skills. However, the same study highlighted that some mastery could be facilitated through online learning like history taking. A study conducted by Ross 41 among medical and nursing students identified that supervision of clinical learning was affected due to Covid-19 restrictions, and this had an impact on the development of psychomotor skills.

Delivery of dental practical was adversely affected by COVID-19 non-contact policies until they developed a portable teaching platform to facilitate whole remote and physical distance teaching and learning. The platform offers procedural synchronized practical learning with the instructor and student using real-time video, audio, and posture and gives the instructor and students feedback. 48 Online teaching and learning call for a more innovative mechanism of teaching practice for students. This can be possible with good funding and software.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Covid-19 brought many challenges in all sectors, and the education system is also affected by its related policies and regulation. Policies and regulations related to lockdown and social distance compelled all teaching and learning institutions to adjust their mode of delivery. A move to online learning was adopted and unfamiliar to all, especially in the rural areas of South Africa, given the scarcity of resources. Nursing undergraduate students also had to adapt to the new teaching and learning where clinical learning was a significant challenge. To facilitate clinical learning, the institutions should have a dedicated preceptor at all the clinical sites to supervise the clinical learning of the nursing student and attend to their learning and social needs.

Lack of gadgets, poor or no connectivity, lack of data related to poor socio-economic background, and unfamiliar programs are some of the conditions they had to deal with. Most of these challenges were found to be universal worldwide. It can be concluded that the University needs to put more resources and innovative strategies to facilitate effective online teaching and learning.

The introduction of a new learning modality should be accompanied by a thorough orientation of both learners and lecturers to facilitate effective learning. There should be a mechanism of addressing the developing problems related to online teaching and learning on time so that these problems are resolved as the people involved in the program are not in the same place. Information regarding the experienced problems should also be communicated to all parties involved.

Clinical teaching and learning have proved to be very difficult to accomplish. Lecturers must develop innovative teaching methods and expose nursing students to clinical learning to acquire their psychomotor skills and enhance their professional conduct. Collaboration within the faculty and outside the faculty should be explored to share ideas to improve clinical learning. The University should try to assist students in acquiring the necessary gadgets to participate in online learning effectively. This could be achieved by always having emergency funds used in a crisis, especially for needy students.

The home environment also contributes to effective learning. Students reporting unconducive home environments could be referred to social workers for assistance or given temporary shelter within university premises. More research needs to be undertaken related to online teaching and learning, especially in poorly resourced universities, to implement the best strategies to make it more effective.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this paper wish to express their gratitude to the nursing students who participated in the study.

Authors’ Information: ML is an Associate Professor in the Department of Public Health, University of Venda; MOP is the PhD candidate in the Department of Psychology; LRT is a Research Professor in the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Venda; LM is an intern (research assistant); and CMJ is a research assistant in the research office, faculty of Health Sciences, University of Venda. MT was a part-time lecturer under the Department of Public Health, and MMT is the Dean of the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Venda.

Author contributions: ML, MOP, LRT, LM, and MMT conceptualized the study (design and methods), collected and analyzed data. ML, MOP, LM conducted the literature review and literature control for the study findings. ML, MOP, LM, MT, LRT, MMT, and CMJ wrote, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by the University of Venda Research and Publication Committee (URPC), South Africa. However, a funder provided funds for this research; the funder was not actively involved in the research process.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: The study was approved by the Human Clinical Trial Research Ethics Committee of the University of Venda (Ethical clearance number: SHS/20/PH/13/2606). All the participants signed an electronic, written consent form before they responded to the open-ended questions. An electronic information sheet provided them with additional information about the study’s voluntariness. Additionally, the participants volunteered and were not coerced into participating in the study. With password-encrypted codes, participants’ confidentiality and anonymity were guaranteed. Human subjects were studied following the Helsinki Declaration on the protection of human subjects.

- 1. Reimers F, Schleicher A, Saavedra J, Tuominen S. Supporting the continuation of teaching and learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic. OECD. 2020;1(1):1-38. https://www.oecd.org/education/Supporting-the-continuation-of-teaching-and-learning-during-the-COVID-19-pandemic.pdf [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Reimers FM, Schleicher A. A framework to guide an education response to the COVID-19 Pandemic of 2020. OECD. 2020;14:2020-2104. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=126_126988-t63lxosohs&title=A-framework-to-guide-an-education-response-to-the-Covid-19-Pandemic-of-2020 [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. García E, Weiss E. COVID-19 and Student Performance, Equity, and US Education Policy: Lessons from Pre-pandemic Research to Inform Relief, Recovery, and Rebuilding. Economic Policy Institute. Washington, DC: EPI Publications. 2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Peters MA, Wang H, Ogunniran MO, et al. China’s internationalized higher education during Covid-19: Collective student autoethnography. Postdigital science and education. 2020;2:968-988. doi: 10.1007/s42438-020-00128-1 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Dhawan S. Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. J Educ Technol Syst. 2020;49(1):5-22. doi: 10.1177/0047239520934018 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Sintema EJ. Effect of COVID-19 on the Performance of Grade 12 Students: Implications for STEM Education. EURASIA J Math Sci Tech Ed. 2020;16(7):em1851. doi: 10.29333/ejmste/7893 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Masuku MM. Emergency remote teaching in higher education during COVID-19: challenges and opportunities. International Journal of Higher Education. 2021;10(5):1. https://openscholar.ump.ac.za/bitstream/20.500.12714/361/3/Emergency-remote-teaching-in-higher-education-during-Covid-19-challenges-and-opportunities.pdf [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Patrick HO, Abiolu RT, Abiolu OA. Reflections on COVID-19 and the viability of curriculum adjustment and delivery options in the South African educational space. Transformation in Higher Education. 2021;6:101. [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Ali W. Online and remote learning in higher education institutes: A necessity in light of COVID-19 pandemic. High Educ Stud. 2020;10(3):16-25. [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. van Schalkwyk F. Reflections on the public university sector and the covid-19 Pandemic in South Africa. Stud High Educ. 2021;46(1):44-58. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2020.1859682 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Ngwacho AG. COVID-19 pandemic impact on Kenyan education sector: Learner challenges and mitigations. Journal of Research Innovation and Implications in Education. 2020;4(2):128-139. [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Li Y, Nishimura N, Yagami H, Park H-S. An empirical study on online learners’ continuance intentions in China. Sustainability. 2021;13(2):889. doi: 10.3390/su13020889 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Muthuprasad T, Aiswarya S, Aditya KS, Jha GK. Students’ perception and preference for online education in India during COVID-19 Pandemic. Social Sciences & Humanities Open. 2021;3(1):100101. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100101 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Beaunoyer E, Dupéré S, Guitton MJ. COVID-19 and digital inequalities: Reciprocal impacts and mitigation strategies. Comput Hum Behav. 2020;111:106424. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106424 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Primdahl N, Borsch A, Verelst A, Jervelund S, Derluyn I, Skovdal M. ‘It’s difficult to help when I am not sitting next to them’: How COVID-19 school closures interrupted teachers’ care for newly arrived migrant and refugee learners in Denmark. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2020;16(1):75-85. doi: 10.1080/17450128.2020.1829228 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Hussein E, Daoud S, Alrabaiah H, Badawi R. Exploring undergraduate students’ attitudes towards emergency online learning during COVID-19: A case from the UAE. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;119:105699. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105699 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Kim D, Lee Y, Leite WL, Huggins-Manley AC. Exploring student and teacher usage patterns associated with student attrition in an open educational resource-supported online learning platform. Comput Educ. 2020;156:103961. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103961 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Hedding DW, Greve M, Breetzke GD, Nel W, van Vuuren BJ. COVID-19 and the academe in South Africa: Not business as usual. S. Afr. j. sci. [Internet]. 2020;116(7-8):1-3. doi: 10.17159/sajs.2020/8298 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Bryson JR, Andres L. Covid-19 and rapid adoption and improvisation of online teaching: curating resources for extensive versus intensive online learning experiences. J Geogr High Educ. 2020;44(4):608-623. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2020.1807478 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Chen JC, Dobinson T, Kent S. Students’ perspectives on the impact of blackboard collaborate on open university Australia (OUA) online learning. Journal of Educators Online. 2020;17(1):n1. [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Safdar G, Rauf A, Ullah R, Rehman AU. Exploring factors leading to quality online learning in the era of Covid-19: A correlation model study. Universal Journal of Educational Research. 2020;8(12A):7324-7329. doi: 10.13189/ujer.2020.082515. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Brook J, Kemp C. Flexible rostering in nursing student clinical placements: A qualitative study of student and staff perceptions of the impact on learning and student experience. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;54:103096. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103096 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Brook J, Aitken L, MacLaren JA, Salmon D. Co-production of an intervention to increase retention of early career nurses: Acceptability and feasibility. Nurse Education in Practice. 2020;47:102861. DOI: 10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102861 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Capone V, Caso D, Donizzetti AR, Procentese F. University student mental well-being during COVID-19 Outbreak: What are the relationships between information seeking, perceived risk and personal resources related to the academic context? Sustainability. 2020;12(17):7039. doi: 10.3390/su12177039 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Kim H, Sefcik JS, Bradway C. Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: A systematic review. Res Nurs Health. 2017;40(1):23-42. doi: 10.1002/nur.21768 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Lambert VA, Lambert CE. Qualitative descriptive research: An acceptable design. Pacific Rim International Journal of Nursing Research. 2012;16(4):255-256. [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Grove S, Burns N, Gray J. The Practice of Nursing Research. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier/Saunders; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. University of Venda Registry. University of venda mission and vision. 2018. http://www.univen.ac.za/mission-vision/ . Accessed May 3, 2019.

- 29. Mason M. Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum Qual Soc Res, 2010;11(3). doi: 10.17169/fqs-11.3.1428 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Braun V, Clarke V, Boulton E, Davey L, McEvoy C. The online survey as a qualitative research tool. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2020:1-14. DOI: 10.1080/13645579.2020.1805550 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Vasantha Raju N, Harinarayana NS. Online survey tools: A case study of Google Forms. National Conference on Scientific, Computational & Information Research Trends in Engineering, GSSS-IETW, Mysore. 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Bengtsson M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open. 2016;2:8-14. [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Lincoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Delfino M, Manca S, Persico D, Sarti L. Online learning: Attitudes, expectations and prejudices of adult novices. Proceedings of the IASTED Web-Based Education Conference. 2004:31–36. [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Wang M, MacArthur DA, Crosby B. A descriptive study of community college teachers’ attitudes toward online learning. TechTrends. 2003;47(5):28–31. doi: 10.1007/BF02763202. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Yusoff MSB, Hadie SNH, Mohamad I, et al. Sustainable medical teaching and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Surviving the new normal. Malays J Med Sci. 2020;27(3):137-142. doi: 10.21315/mjms2020.27.3.14 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Abbasi S, Ayoob T, Malik A, Memon SI. Perceptions of students regarding E-learning during Covid-19 at a private medical college. Pak J Med Sci. 2020;36(COVID19-S4):S57-S61. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2766. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Pokhrel S, Chhetri R. A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. Higher Education for the Future. 2021;8(1):133-141. doi: 10.1177/2347631120983481 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Mukhtar K, Javed K, Arooj M, Sethi A. Advantages, limitations and recommendations for online learning during COVID-19 pandemic era. Pak J Med Sci. 2020;36(COVID19-S4):S27-S31. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2785. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Ross DA. Creating a “quarantine curriculum” to enhance teaching and learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Acad Med. 2020;95(8):1125-1126. doi: 10.1097/2FACM.0000000000003424. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Andrade MS, Miller RM, Kunz MB, Ratliff JM. Online learning in schools of business: The impact of quality assurance measures. J Educ Bus. 2020;95(1):37-44. doi: 10.1080/08832323.2019.1596871. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Wanner T, Palmer E. Personalising learning: Exploring student and teacher perceptions about flexible learning and assessment in a flipped university course. Comput Educ. 2015;88:354-369. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2015.07.008. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Bolliger D, Supanakorn S, Boggs C. Impact of podcasting on student motivation in the online learning environment. Comput Educ. 2010;55(2):714-722. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2010.03.004. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Murphy A, Farley H, Lane M, Hafeez-Baig A, Carter B. Mobile learning anytime, anywhere: What are our students doing? Australasian Journal of Information Systems. 2014;18(3). doi: 10.3127/ajis.v18i3.1098. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Roberts N, Rees M. Student use of mobile devices in university lectures. Australas J Educ Technol. 2014;30(4). doi: 10.14742/ajet.589. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. García-Martínez I, Fernández-Batanero J, Cobos Sanchiz D, Luque de la Rosa A. Using mobile devices for improving learning outcomes and teachers’ professionalization. Sustainability. 2019;11(24):6917. doi: 10.3390/su11246917. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Cheng L, Kalvandi M, McKinstry S. et al. Application of denteach in remote dentistry teaching and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study. Front Robot AI. 2021;7. doi: 10.3389/frobt.2020.611424. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (509.9 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

A qualitative descriptive study of the COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on nursing care delivery in the critical care work system

Claire bethel, jessica g rainbow, karen johnson.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author. The University of Arizona, 1305 N. Martin Rd, Tucson, AZ, 85721, USA.

Received 2021 Aug 30; Revised 2022 Jan 27; Accepted 2022 Feb 9; Issue date 2022 Jul.

Since January 2020 Elsevier has created a COVID-19 resource centre with free information in English and Mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID-19. The COVID-19 resource centre is hosted on Elsevier Connect, the company's public news and information website. Elsevier hereby grants permission to make all its COVID-19-related research that is available on the COVID-19 resource centre - including this research content - immediately available in PubMed Central and other publicly funded repositories, such as the WHO COVID database with rights for unrestricted research re-use and analyses in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source. These permissions are granted for free by Elsevier for as long as the COVID-19 resource centre remains active.

The COVID-19 pandemic drastically changed the delivery of nursing care in U.S. critical care settings. The purpose of this study was to describe nurses’ perceptions of the critical care work system during the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. We conducted interviews with experienced critical care nurses who worked during the pandemic and analyzed these data using deductive content analysis framed by the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) 2.0 model. Concepts include the critical care work system structures, nursing care processes, outcomes, and adaptations during the pandemic. Our findings revealed a description of the critical care work system framed by the SEIPS 2.0 model. We suggest how human factors engineers can utilize a human factors and engineering approach to maximize the adaptations critical care nurses made to their work system during the pandemic.

Keywords: Critical care, Nursing, Care delivery, Work system, COVID-19, Redesign

1. Introduction

The U.S. has recorded almost 80 million cases and over 870,000 deaths due to COVID-19 ( Centers for Disease Control, 2021 ). The COVID-19 pandemic led to an enormous increase in admissions to critical care settings ( Huang et al., 2020 ), and subsequently, an unprecedented need for critical care nurses. In addition to a shortage of nurses there was also a shortage of resources such as inadequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and ventilators. These changes resulted in sweeping changes to the way nursing care was delivered in U.S. critical care settings. Little is yet known about the impact of these changes on nursing care in critical care work systems.

Prior to the pandemic, trained critical care nurses did the majority of patient care in critical care ( Brilli et al., 2001 ). Typical nurse to patient ratios were 1:1 or 1:2 depending on state mandated staffing ratios ( Brilli et al., 2001 ). Low ratios facilitated the critical care nurse's ability to focus on fewer patients each shift while providing complex, life-sustaining care ( Brilli et al., 2001 ). Critical care nurses are essential to providing complete patient care and attend to complex patient care tasks; less complex tasks are delegated to nursing assistive personnel ( Shirey, 2008 ).

While the COVID-19 pandemic added complexity and stress to nurses' critical care work system, it also highlighted the baseline imbalance of demands and capacity across multiple areas of nurses’ work. Nursing documentation was a significant burden for nurses due to its level of detail and frequency ( Collins et al., 2018 ). Critical care nurses experienced high rates of burnout ( Moss et al., 2016 ), moral distress ( Sirilla et al., 2017 ) and turnover ( Nursing Solutions Inc., 2019 ). Communication has historically been a challenge between critical care team members and the patient and family ( Grant, 2015 ). There were also not enough nurses to meet the demand for nursing care in critical care ( Seda and Parrish, 2019 ). Understanding nursing care in critical care work systems is important because nursing care is linked to patient and nurse outcomes ( Cheung et al., 2008 ), which impact organizational outcomes.

According to a study by The International Council of Nurses ( ICN, 2021 ), the COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted nurse outcomes. A majority (76%) of nurses reported on average a three-fold increase in nurse-to-patient ratios (number of nurses who care for a number of patients), which nurses reported as contributing to their exhaustion, burnout, and stress ( ICN, 2021 ). Increased nurse-to-patient ratios (having fewer nurses for more patients) and burnout are not only dangerous to nurses but can also be harmful to patients ( ICN, 2021 ). For every extra patient per nurse, Aiken et al. (2002) found a 7% increase in the odds of patient failure-to-rescue and a 7% increase in the likelihood of dying within 30 days. Nurse burnout is associated with turnover, poor patient outcomes ( Bae et al., 2010 ), and medical errors ( Hall et al., 2016 ), which all have significant financial impact on hospitals ( Hirose et al., 2018 ). The pandemic intensified the thin financial margins for hospitals, or even caused them to close their doors, as many experienced low patient censuses due to hospital avoidance early in the pandemic. Nationwide, hospitals experienced a collective $36.6 billion loss from March to June 2020 ( American Hospital Association, 2020 ). Patient care in critical care settings is very expensive ( Reardon et al., 2018 ). Considering the link between nursing care with patient, nurse, and organizational outcomes, nursing care in critical care work systems should be further understood. To persevere financially through and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, organizations should consider ways to redesign the critical care work system. Furthermore, a systems approach is recommended to mitigate clinician burnout ( NAM, 2009 ), which urgently needs addressing for nurses' well-being.

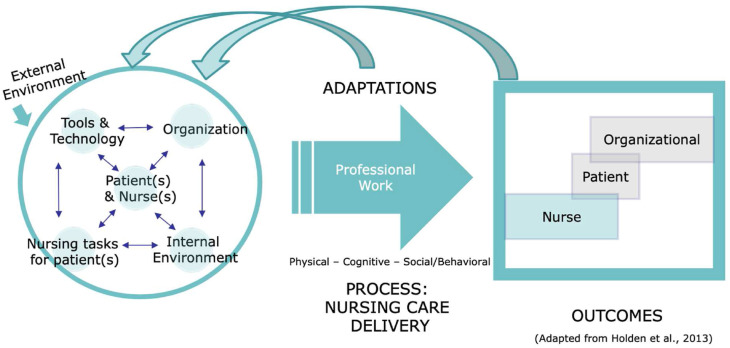

Carayon and Perry (2021) suggest use of the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) model ( Carayon et al., 2006 ) as a human factors and ergonomics approach for healthcare systems to redesign work systems in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In the SEIPS model, Carayon et al. (2006) combined the work system model described by Smith and Carayon (2001) with Donabedian's (1988) Quality (structure-process-outcome) Model. The SEIPS model ( Carayon et al., 2006 ) is comprised of interconnected concepts including the work system (person, organization, task(s), tools & technology, and physical environment), processes (care and other), and outcomes (patient, employee, and organizational). SEIPS also incorporates Balance Theory which emphasizes the interconnectedness of the work system to adapt or facilitate overcoming barriers ( Smith and Carayon, 2001 ; Smith and Carayon-Sainfort, 1989 ). Holden et al. (2013) described a SEIPS 2.0 model in which the work system construct includes the concepts of internal and external environments, the work processes are described as physical, cognitive, and social/behavioral, and added adaptation as a concept to describe the feedback mechanism to explain the evolution of work systems ( Holden et al., 2013 ). See Fig. 1 for how the SEIPS 2.0 model has been applied for use in this study.

SEIPS 2.0 Model in this study.

Researchers suggest the COVID-19 pandemic impacted nursing care broadly in healthcare systems ( Schroeder et al., 2020 ; Aliyu et al., 2021 ); however, little research has focused specifically on nurses’ perceptions of the changes in nursing care in U.S. critical care work systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. Critical care work systems are structures that organize the provision of healthcare ( Holden et al., 2013 ) for critically ill patients experiencing life-threatening illness ( Marshall et al., 2017 ). The purpose of this study was to describe the critical care work system during the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. from the perceptions of nurses. The study aims were to:

Describe nurses' perceptions of the critical care work system during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Describe nurses' perceptions of how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the critical care work system, changed the processes and outcomes, and influenced adaptation.

2.1. Participants

We recruited critical care Registered Nurses via multiple venues, including social media (Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn), several large hospitals in the Southwest U.S., nursing organizations, and doctoral nursing students at [redacted]. Potential participants clicked a link to complete a screening questionnaire in Qualtrics (2021) . They indicated their interest to participate and input their email address. The principal investigator (CB) reached out to potential participants via email to schedule an interview. Inclusion criteria were two or more years of experience working in an intensive care unit (ICU) in the U.S. and provided care for adult patients in the ICU for at least one month during the COVID-19 pandemic. We selected these criteria to ensure participants accrued substantial experience working in critical care both prior to, and during, the pandemic.

2.2. Procedures

The principal investigator (CB) developed a semi-structured interview guide based on the SEIPS 2.0 model. The guide included interview questions about nurses’ experiences with care; descriptions of the critical care work system structures, care processes, and outcomes; and the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. CB piloted interview questions with two nurses who met the inclusion criteria but did not participate in the study; the questions provoked rich responses, including descriptions of the critical care work system, nursing care processes, adaptations, and associated outcomes. Therefore, no changes were made to the interview guide.

We obtained institutional review board approval for the study prior to participant recruitment and data collection. CB conducted one interview with each participant using an online conference software with audio-only recording. Participants gave verbal consent at the beginning of the video-platform interview. Interviews took place in mid-April 2021 and lasted on average 32.4 min, in part because the participants were particularly eager to discuss the topics and were quite open with CB (who is experienced both as a nurse and as a semi-structured interviewer for qualitative descriptive research). The shortest interview lasted 25 min and the longest interview lasted 40 min. Participants received a $15 e-gift card as compensation for participation. We de-identified audio recordings by removing information, such as participant name or place of work, and replaced with “redacted.” Transcripts were transcribed verbatim using a HIPAA-certified service before uploading to Dedoose (2020) qualitative analysis software.

2.2.1. Data analysis

We analyzed interview transcripts using a deductive content analysis approach framed by the SEIPS 2.0 model. Deductive content analysis is an approach whereby codes are applied using concepts from existing theories for the purpose of supporting or extending an existing theory ( Elo and Kyngas, 2007 ). After uploading transcripts into Dedoose, CB and JR randomly selected three and coded them independently using a codebook. CB and JR then reviewed each section of the transcripts to ensure consistent application of codes and code definitions. The remaining 17 interviews were coded independently by both coders, reviewing each disagreement identified in Dedoose. We documented and saved each stage of data analysis as separate versions ( Lincoln and Guba, 1985 ). After coding all interviews and ensuring 100% agreement, CB shared a presentation via email of the codes with definitions and exemplar quotes to three critical care nurses (who met the study inclusion criteria but were not recruited for the study) to serve as member checks to support credibility and transferability ( Lincoln and Guba, 1985 ). They were then individually asked for feedback on whether the codes and exemplars were representative of their own experience. Each of these nurses described the exemplars as “difficult to read,” yet reflected experiences that were very similar to their own experiences.

Twenty experienced critical care nurses (15 women, 5 men) ranging in age from 27 to 50 years old participated in this study and were from a variety of geographic regions of the US: Southwest (11), West (1) Northwest (2), Northeast (4), and Southeast (2). Participants reported working on their “home” units including surgical, trauma, medical, neurology, and cardiac/cardiovascular critical care units. One participant moved from working on a pediatric to an adult critical care unit during the COVID-19 pandemic. See Table 1 for demographics.

Participant demographics.

We used the SEIPS 2.0 model as a framework for deductive content analysis to describe nurses’ experiences providing care in the critical care work system during the COVID-19 pandemic and how nurses adapted nursing care to avoid the impacts of system barriers on patients. Below we report on the elements from each of the main concepts (work system, processes, outcomes, and adaptations) of the SEIPS 2.0 model. In Table 2 we provide a summary of exemplar quotes.

The quotes in this table are representative of participants' descriptions of each of the elements of the SEIPS 2.0 model.

3.1. The critical care work system during the COVID-19 pandemic

Nurses’ descriptions of the work system elements aligned with the SEIPS 2.0 model; including the elements of critical care nurses, critical care patients, nursing tasks for the patient, tools and technology, organization, and internal and external environments.

3.1.1. Patients

Participants described the patients as critically ill and isolated from their family members. These were some of the most critically ill (COVID-19 and other diagnoses) patients the participants had ever cared for (see Table 2 ); as they required intravenous vasoactive medications, steroids, continuous renal replacement therapy, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and early mechanical ventilation.

3.1.2. Critical care nurses

The critical care nurse participants in this study were experienced (see Table 2 , Table 1 for demographics) and described themselves and their colleagues as detail-oriented. During the pandemic participants primarily provided direct nursing care for patients alongside nurses who were redeployed from other departments (neonatal ICU, obstetrics, perioperative settings).

3.1.3. Nursing tasks for the patient

Critical care nurse participants performed both typical critical care nursing tasks for the patient and atypical tasks that, during non-pandemic times, would be performed by other health care professionals. For example, nurses were at times the only ones allowed to enter patient rooms, so they communicated with respiratory therapists to obtain guidance on managing ventilators (see Table 2 ). These tasks are not typically required of critical care nurses. Additionally, they were required to delegate tasks to re-deployed nurses. Participants noted inconsistencies in the amount and type of critical care training deployed nurses received, which therefore impacted the tasks they were able to assist with, which participants described as a major barrier to care.

3.1.4. Tools & technology

The participants indicated tools, such as PPE, were in short supply, and staff were forced to reuse or purchase their own PPE. Aging and outdated equipment was a common experience among participants due to shortages (see Table 2 ). Nurses described difficulty managing aging ventilators that had been decommissioned. Masks became a barrier to communication among the interdisciplinary team; the masks made it difficult to hear coworkers’ muffled voices over negative pressure ventilation systems. The technology participants used to facilitate patient-family communication included iPad tablets supplied by the organization. In many instances organization-supplied technology for patient-family communication was not available, therefore, nurses accomplished this by using their own personal cell phones. There were also inconsistent documentation standards throughout the cycles of the pandemic. For example, several participants described feeling unsure because what was required for them to document on their patients were constantly changing. Many felt communication within the electronic health record (EHR) could have facilitated appropriate documentation.

3.1.5. Organization

Participants recounted organizational policies that constantly changed due to evolving knowledge of COVID-19 and different experiences with both unit and organization-level leadership. Policies regarding visitor restrictions were modified according to the severity of the pandemic. Some participants described leaders who clearly facilitated communication of changes and the status of resources (such as PPE), while others described leaders who were barriers to staff understanding change and lack of available resources (see Table 2 ). Participants described a general feeling of frustration with the leaders’ decisions to bring redeployed nurses to critical care with insufficient training; they felt the redeployed nurses were not able to provide assistance that was meaningful to the critical care nurses.

3.1.6. Internal environment

Participants described the internal environment of the ICUs as being retrofitted to meet patient care needs during the pandemic. Multiple participants shared how organizations created ICUs in settings that previously were used for different patient populations (eg. pediatric intensive care or unused units). As a result, several participants described cumbersome negative pressure equipment that was in the way or completely changed the environment of the unit (see Table 2 ). One participant even described how their organization resorted to opening the windows in the peak heat of the summer to create negative pressure in patient rooms.

3.1.7. External environment

Participants described considerable influence of the external environment on the critical care work system. Nurses indicated that group gatherings in the community and the general public's anti-mask sentiment directly impacted the patients, healthcare professionals, the organization, and the community. Several participants described taking care of critical care patients who did not believe they had COVID-19 despite a positive diagnosis. Consequently, participants felt frustration with political leaders for not communicating the severity of COVID-19 illness and with their community for not believing the reality of COVID-19 illness and its reverberating impacts. Participants described this as impacting not only the number of patients admitted to the ICU, but also nurse morale and the way patients' family members treated nurses.

3.2. The process of nursing care

3.2.1. physical work processes.

Participants recounted the physical work of nursing care as exhausting due to manual proning (turning a patient onto their abdomen) of patients and frequent cardiopulmonary resuscitations (see Table 2 ). Physical work was often also described as emotionally exhausting as their patients frequently died. Nurses described completing most of the patient care with fewer staff. They spent significant time donned in PPE to deliver care and facilitate video chats between patients and their family. Participants described the physical work of putting on and taking off of PPE as time-consuming, which impacted the way nursing care was delivered because care had to be done all together at the same time instead of as-needed.

3.2.2. Cognitive work processes