This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Bashir Y, Conlon KC. Step by step guide to do a systematic review and meta-analysis for medical professionals. Ir J Med Sci. 2018; 187:(2)447-452 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-017-1663-3

Bettany-Saltikov J. How to do a systematic literature review in nursing: a step-by-step guide.Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2012

Bowers D, House A, Owens D. Getting started in health research.Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011

Hierarchies of evidence. 2016. http://cjblunt.com/hierarchies-evidence (accessed 23 July 2019)

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2008; 3:(2)37-41 https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Developing a framework for critiquing health research. 2005. https://tinyurl.com/y3nulqms (accessed 22 July 2019)

Cognetti G, Grossi L, Lucon A, Solimini R. Information retrieval for the Cochrane systematic reviews: the case of breast cancer surgery. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2015; 51:(1)34-39 https://doi.org/10.4415/ANN_15_01_07

Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006; 6:(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-6-35

Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Sinclair JC Users' guides to the medical literature IX. A method for grading health care recommendations. JAMA. 1995; 274:(22)1800-1804 https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1995.03530220066035

Hanley T, Cutts LA. What is a systematic review? Counselling Psychology Review. 2013; 28:(4)3-6

Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. 2011. https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org (accessed 23 July 2019)

Jahan N, Naveed S, Zeshan M, Tahir MA. How to conduct a systematic review: a narrative literature review. Cureus. 2016; 8:(11) https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.864

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1997; 33:(1)159-174

Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R, Cheraghi-Sohi S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014; 14:(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009; 6:(7) https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Mueller J, Jay C, Harper S, Davies A, Vega J, Todd C. Web use for symptom appraisal of physical health conditions: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017; 19:(6) https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6755

Murad MH, Asi N, Alsawas M, Alahdab F. New evidence pyramid. Evid Based Med. 2016; 21:(4)125-127 https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmed-2016-110401

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance. 2012. http://nice.org.uk/process/pmg4 (accessed 22 July 2019)

Sambunjak D, Franic M. Steps in the undertaking of a systematic review in orthopaedic surgery. Int Orthop. 2012; 36:(3)477-484 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-011-1460-y

Siddaway AP, Wood AM, Hedges LV. How to do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annu Rev Psychol. 2019; 70:747-770 https://doi.org/0.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008; 8:(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

Wallace J, Nwosu B, Clarke M. Barriers to the uptake of evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses: a systematic review of decision makers' perceptions. BMJ Open. 2012; 2:(5) https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001220

Carrying out systematic literature reviews: an introduction

Alan Davies

Lecturer in Health Data Science, School of Health Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester

View articles · Email Alan

Systematic reviews provide a synthesis of evidence for a specific topic of interest, summarising the results of multiple studies to aid in clinical decisions and resource allocation. They remain among the best forms of evidence, and reduce the bias inherent in other methods. A solid understanding of the systematic review process can be of benefit to nurses that carry out such reviews, and for those who make decisions based on them. An overview of the main steps involved in carrying out a systematic review is presented, including some of the common tools and frameworks utilised in this area. This should provide a good starting point for those that are considering embarking on such work, and to aid readers of such reviews in their understanding of the main review components, in order to appraise the quality of a review that may be used to inform subsequent clinical decision making.

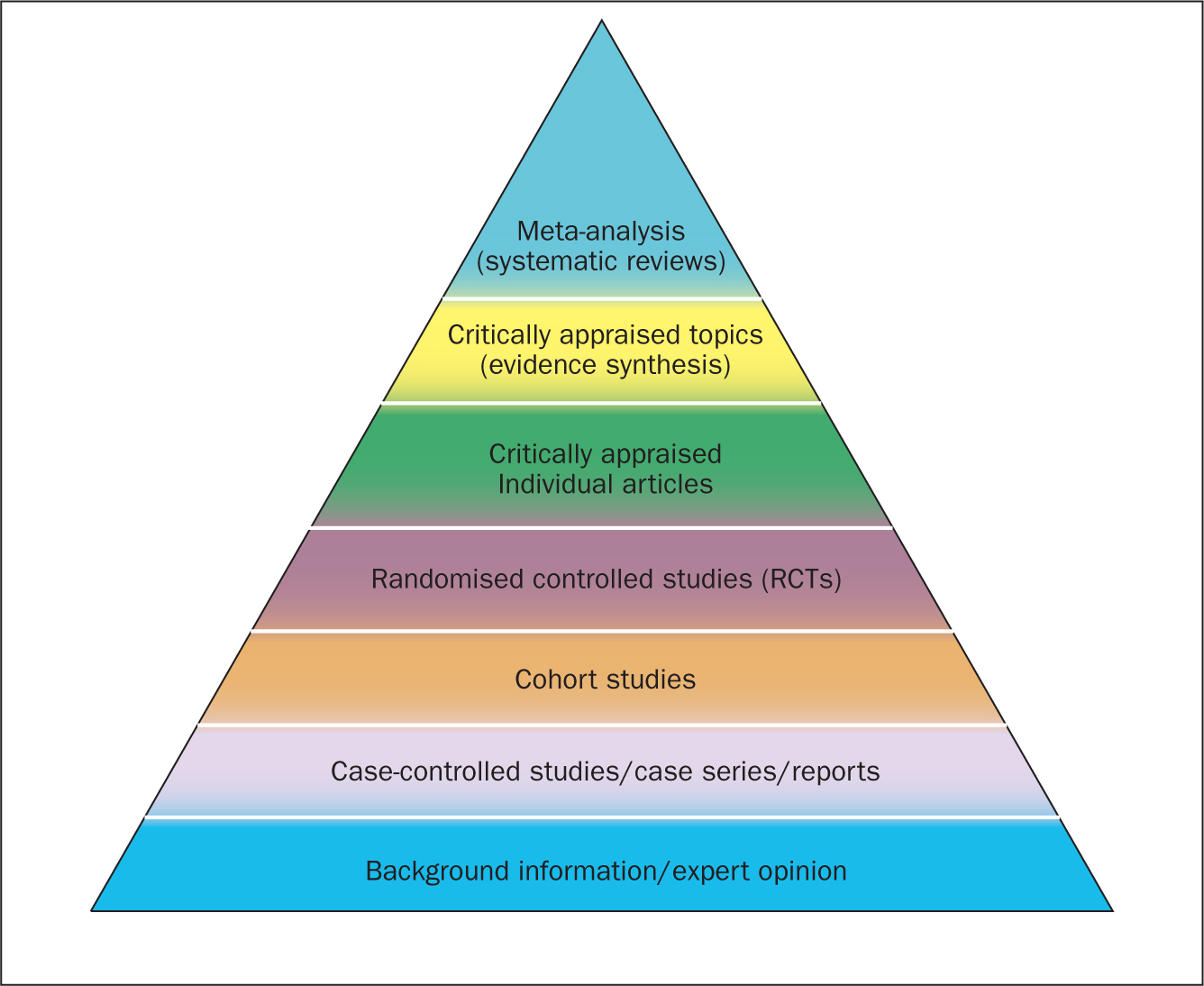

Since their inception in the late 1970s, systematic reviews have gained influence in the health professions ( Hanley and Cutts, 2013 ). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are considered to be the most credible and authoritative sources of evidence available ( Cognetti et al, 2015 ) and are regarded as the pinnacle of evidence in the various ‘hierarchies of evidence’. Reviews published in the Cochrane Library ( https://www.cochranelibrary.com) are widely considered to be the ‘gold’ standard. Since Guyatt et al (1995) presented a users' guide to medical literature for the Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group, various hierarchies of evidence have been proposed. Figure 1 illustrates an example.

Systematic reviews can be qualitative or quantitative. One of the criticisms levelled at hierarchies such as these is that qualitative research is often positioned towards or even is at the bottom of the pyramid, thus implying that it is of little evidential value. This may be because of traditional issues concerning the quality of some qualitative work, although it is now widely recognised that both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies have a valuable part to play in answering research questions, which is reflected by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) information concerning methods for developing public health guidance. The NICE (2012) guidance highlights how both qualitative and quantitative study designs can be used to answer different research questions. In a revised version of the hierarchy-of-evidence pyramid, the systematic review is considered as the lens through which the evidence is viewed, rather than being at the top of the pyramid ( Murad et al, 2016 ).

Both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies are sometimes combined in a single review. According to the Cochrane review handbook ( Higgins and Green, 2011 ), regardless of type, reviews should contain certain features, including:

- Clearly stated objectives

- Predefined eligibility criteria for inclusion or exclusion of studies in the review

- A reproducible and clearly stated methodology

- Validity assessment of included studies (eg quality, risk, bias etc).

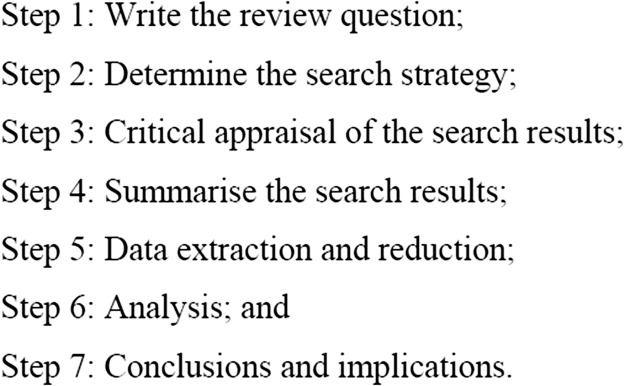

The main stages of carrying out a systematic review are summarised in Box 1 .

Formulating the research question

Before undertaking a systemic review, a research question should first be formulated ( Bashir and Conlon, 2018 ). There are a number of tools/frameworks ( Table 1 ) to support this process, including the PICO/PICOS, PEO and SPIDER criteria ( Bowers et al, 2011 ). These frameworks are designed to help break down the question into relevant subcomponents and map them to concepts, in order to derive a formalised search criterion ( Methley et al, 2014 ). This stage is essential for finding literature relevant to the question ( Jahan et al, 2016 ).

It is advisable to first check that the review you plan to carry out has not already been undertaken. You can optionally register your review with an international register of prospective reviews called PROSPERO, although this is not essential for publication. This is done to help you and others to locate work and see what reviews have already been carried out in the same area. It also prevents needless duplication and instead encourages building on existing work ( Bashir and Conlon, 2018 ).

A study ( Methley et al, 2014 ) that compared PICO, PICOS and SPIDER in relation to sensitivity and specificity recommended that the PICO tool be used for a comprehensive search and the PICOS tool when time/resources are limited.

The use of the SPIDER tool was not recommended due to the risk of missing relevant papers. It was, however, found to increase specificity.

These tools/frameworks can help those carrying out reviews to structure research questions and define key concepts in order to efficiently identify relevant literature and summarise the main objective of the review ( Jahan et al, 2016 ). A possible research question could be: Is paracetamol of benefit to people who have just had an operation? The following examples highlight how using a framework may help to refine the question:

- What form of paracetamol? (eg, oral/intravenous/suppository)

- Is the dosage important?

- What is the patient population? (eg, children, adults, Europeans)

- What type of operation? (eg, tonsillectomy, appendectomy)

- What does benefit mean? (eg, reduce post-operative pyrexia, analgesia).

An example of a more refined research question could be: Is oral paracetamol effective in reducing pain following cardiac surgery for adult patients? A number of concepts for each element will need to be specified. There will also be a number of synonyms for these concepts ( Table 2 ).

Table 2 shows an example of concepts used to define a search strategy using the PICO statement. It is easy to see even with this dummy example that there are many concepts that require mapping and much thought required to capture ‘good’ search criteria. Consideration should be given to the various terms to describe the heart, such as cardiac, cardiothoracic, myocardial, myocardium, etc, and the different names used for drugs, such as the equivalent name used for paracetamol in other countries and regions, as well as the various brand names. Defining good search criteria is an important skill that requires a lot of practice. A high-quality review gives details of the search criteria that enables the reader to understand how the authors came up with the criteria. A specific, well-defined search criterion also aids in the reproducibility of a review.

Search criteria

Before the search for papers and other documents can begin it is important to explicitly define the eligibility criteria to determine whether a source is relevant to the review ( Hanley and Cutts, 2013 ). There are a number of database sources that are searched for medical/health literature including those shown in Table 3 .

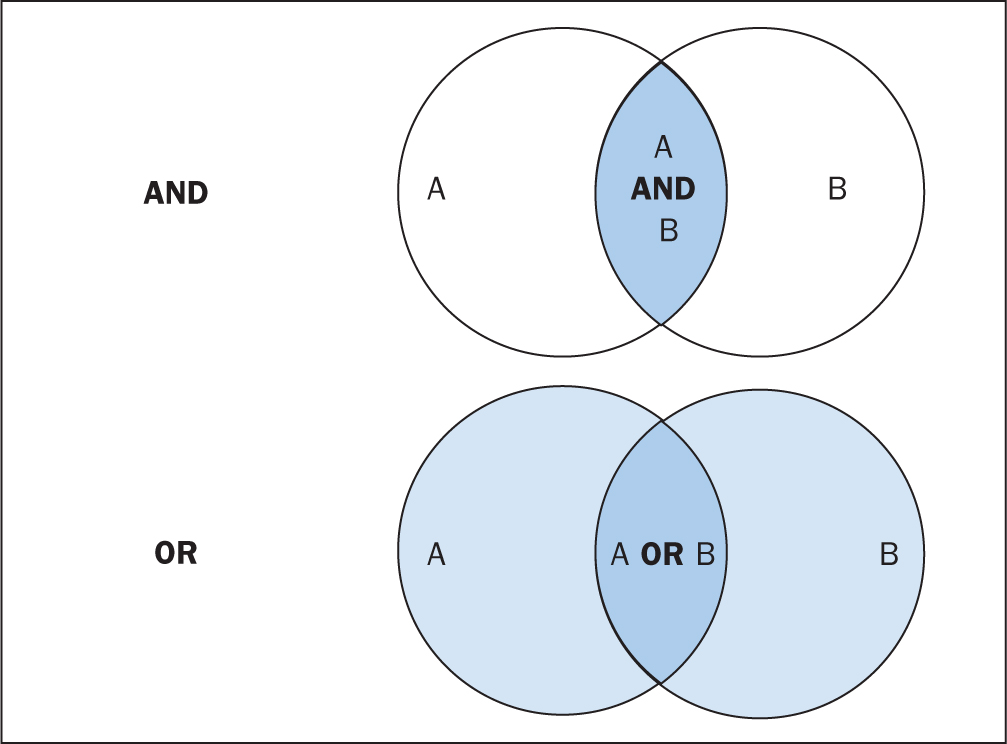

The various databases can be searched using common Boolean operators to combine or exclude search terms (ie AND, OR, NOT) ( Figure 2 ).

Although most literature databases use similar operators, it is necessary to view the individual database guides, because there are key differences between some of them. Table 4 details some of the common operators and wildcards used in the databases for searching. When developing a search criteria, it is a good idea to check concepts against synonyms, as well as abbreviations, acronyms and plural and singular variations ( Cognetti et al, 2015 ). Reading some key papers in the area and paying attention to the key words they use and other terms used in the abstract, and looking through the reference lists/bibliographies of papers, can also help to ensure that you incorporate relevant terms. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) that are used by the National Library of Medicine (NLM) ( https://www.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/meshhome.html) to provide hierarchical biomedical index terms for NLM databases (Medline and PubMed) should also be explored and included in relevant search strategies.

Searching the ‘grey literature’ is also an important factor in reducing publication bias. It is often the case that only studies with positive results and statistical significance are published. This creates a certain bias inherent in the published literature. This bias can, to some degree, be mitigated by the inclusion of results from the so-called grey literature, including unpublished work, abstracts, conference proceedings and PhD theses ( Higgins and Green, 2011 ; Bettany-Saltikov, 2012 ; Cognetti et al, 2015 ). Biases in a systematic review can lead to overestimating or underestimating the results ( Jahan et al, 2016 ).

An example search strategy from a published review looking at web use for the appraisal of physical health conditions can be seen in Box 2 . High-quality reviews usually detail which databases were searched and the number of items retrieved from each.

A balance between high recall and high precision is often required in order to produce the best results. An oversensitive search, or one prone to including too much noise, can mean missing important studies or producing too many search results ( Cognetti et al, 2015 ). Following a search, the exported citations can be added to citation management software (such as Mendeley or Endnote) and duplicates removed.

Title and abstract screening

Initial screening begins with the title and abstracts of articles being read and included or excluded from the review based on their relevance. This is usually carried out by at least two researchers to reduce bias ( Bashir and Conlon, 2018 ). After screening any discrepancies in agreement should be resolved by discussion, or by an additional researcher casting the deciding vote ( Bashir and Conlon, 2018 ). Statistics for inter-rater reliability exist and can be reported, such as percentage of agreement or Cohen's kappa ( Box 3 ) for two reviewers and Fleiss' kappa for more than two reviewers. Agreement can depend on the background and knowledge of the researchers and the clarity of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. This highlights the importance of providing clear, well-defined criteria for inclusion that are easy for other researchers to follow.

Full-text review

Following title and abstract screening, the remaining articles/sources are screened in the same way, but this time the full texts are read in their entirety and included or excluded based on their relevance. Reasons for exclusion are usually recorded and reported. Extraction of the specific details of the studies can begin once the final set of papers is determined.

Data extraction

At this stage, the full-text papers are read and compared against the inclusion criteria of the review. Data extraction sheets are forms that are created to extract specific data about a study (12 Jahan et al, 2016 ) and ensure that data are extracted in a uniform and structured manner. Extraction sheets can differ between quantitative and qualitative reviews. For quantitative reviews they normally include details of the study's population, design, sample size, intervention, comparisons and outcomes ( Bettany-Saltikov, 2012 ; Mueller et al, 2017 ).

Quality appraisal

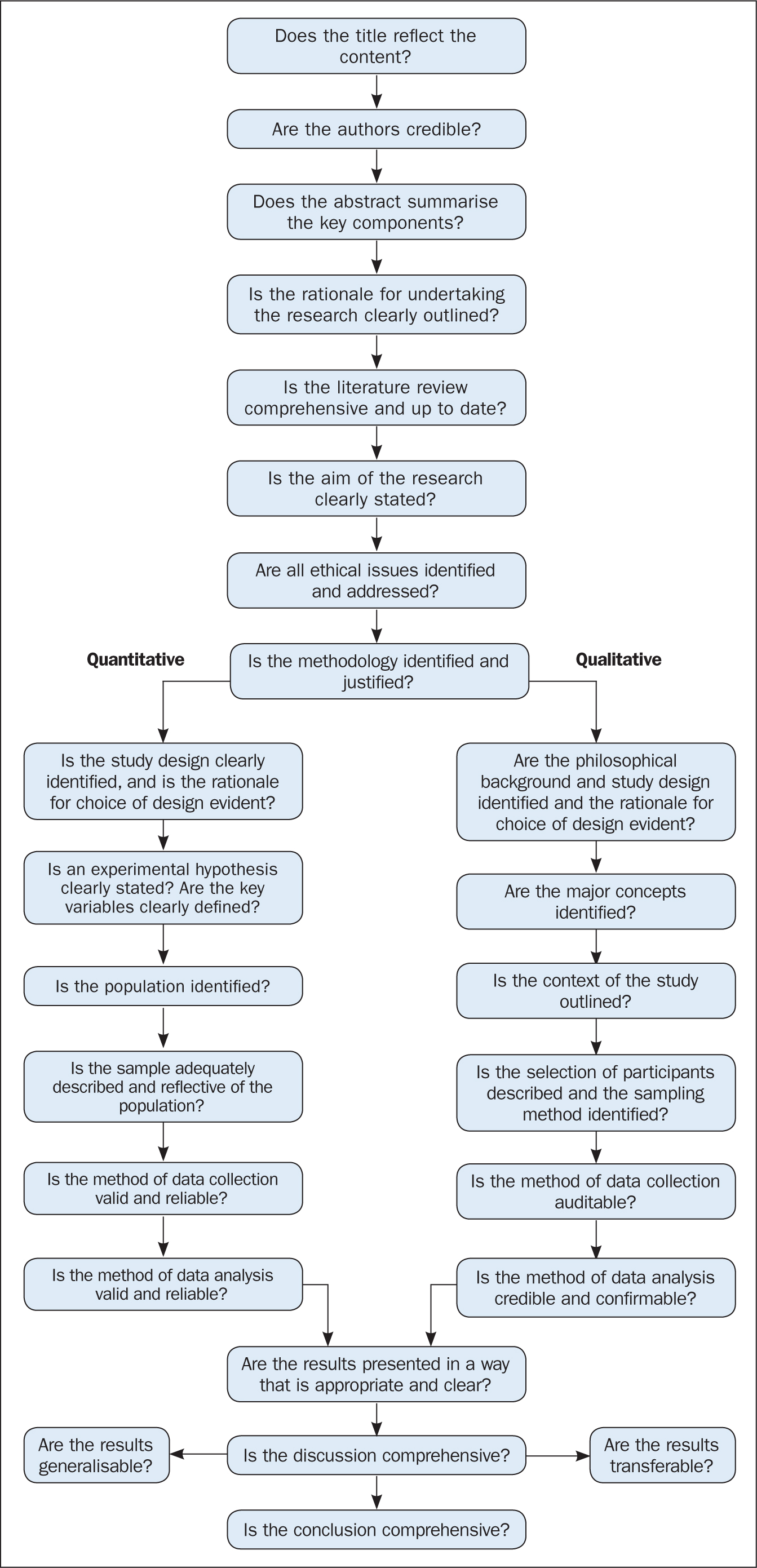

The quality of the studies used in the review should also be appraised. Caldwell et al (2005) discussed the need for a health research evaluation framework that could be used to evaluate both qualitative and quantitative work. The framework produced uses features common to both research methodologies, as well as those that differ ( Caldwell et al, 2005 ; Dixon-Woods et al, 2006 ). Figure 3 details the research critique framework. Other quality appraisal methods do exist, such as those presented in Box 4 . Quality appraisal can also be used to weight the evidence from studies. For example, more emphasis can be placed on the results of large randomised controlled trials (RCT) than one with a small sample size. The quality of a review can also be used as a factor for exclusion and can be specified in inclusion/exclusion criteria. Quality appraisal is an important step that needs to be undertaken before conclusions about the body of evidence can be made ( Sambunjak and Franic, 2012 ). It is also important to note that there is a difference between the quality of the research carried out in the studies and the quality of how those studies were reported ( Sambunjak and Franic, 2012 ).

The quality appraisal is different for qualitative and quantitative studies. With quantitative studies this usually focuses on their internal and external validity, such as how well the study has been designed and analysed, and the generalisability of its findings. Qualitative work, on the other hand, is often evaluated in terms of trustworthiness and authenticity, as well as how transferable the findings may be ( Bettany-Saltikov, 2012 ; Bashir and Conlon, 2018 ; Siddaway et al, 2019 ).

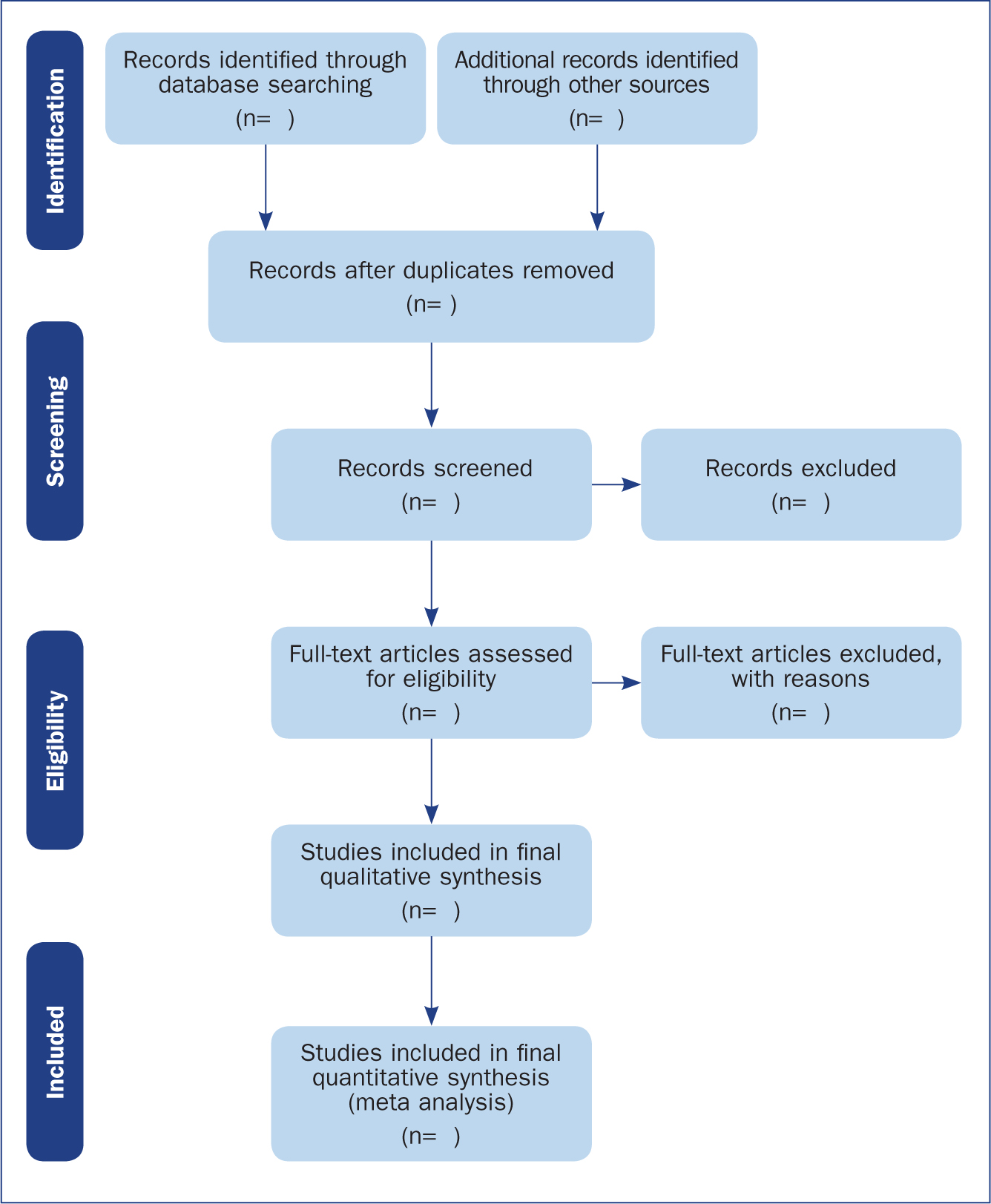

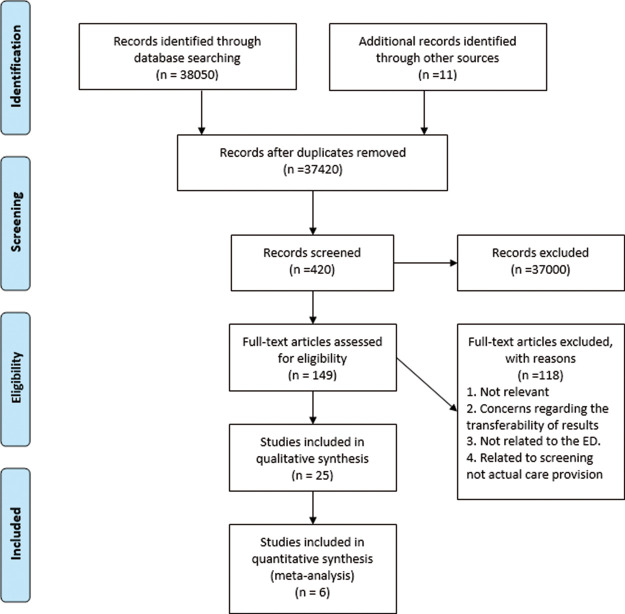

Reporting a review (the PRISMA statement)

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) provides a reporting structure for systematic reviews/meta-analysis, and consists of a checklist and diagram ( Figure 4 ). The stages of identifying potential papers/sources, screening by title and abstract, determining eligibility and final inclusion are detailed with the number of articles included/excluded at each stage. PRISMA diagrams are often included in systematic reviews to detail the number of papers included at each of the four main stages (identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion) of the review.

Data synthesis

The combined results of the screened studies can be analysed qualitatively by grouping them together under themes and subthemes, often referred to as meta-synthesis or meta-ethnography ( Siddaway et al, 2019 ). Sometimes this is not done and a summary of the literature found is presented instead. When the findings are synthesised, they are usually grouped into themes that were derived by noting commonality among the studies included. Inductive (bottom-up) thematic analysis is frequently used for such purposes and works by identifying themes (essentially repeating patterns) in the data, and can include a set of higher-level and related subthemes (Braun and Clarke, 2012). Thomas and Harden (2008) provide examples of the use of thematic synthesis in systematic reviews, and there is an excellent introduction to thematic analysis by Braun and Clarke (2012).

The results of the review should contain details on the search strategy used (including search terms), the databases searched (and the number of items retrieved), summaries of the studies included and an overall synthesis of the results ( Bettany-Saltikov, 2012 ). Finally, conclusions should be made about the results and the limitations of the studies included ( Jahan et al, 2016 ). Another method for synthesising data in a systematic review is a meta-analysis.

Limitations of systematic reviews

Apart from the many advantages and benefits to carrying out systematic reviews highlighted throughout this article, there remain a number of disadvantages. These include the fact that not all stages of the review process are followed rigorously or even at all in some cases. This can lead to poor quality reviews that are difficult or impossible to replicate. There also exist some barriers to the use of evidence produced by reviews, including ( Wallace et al, 2012 ):

- Lack of awareness and familiarity with reviews

- Lack of access

- Lack of direct usefulness/applicability.

Meta-analysis

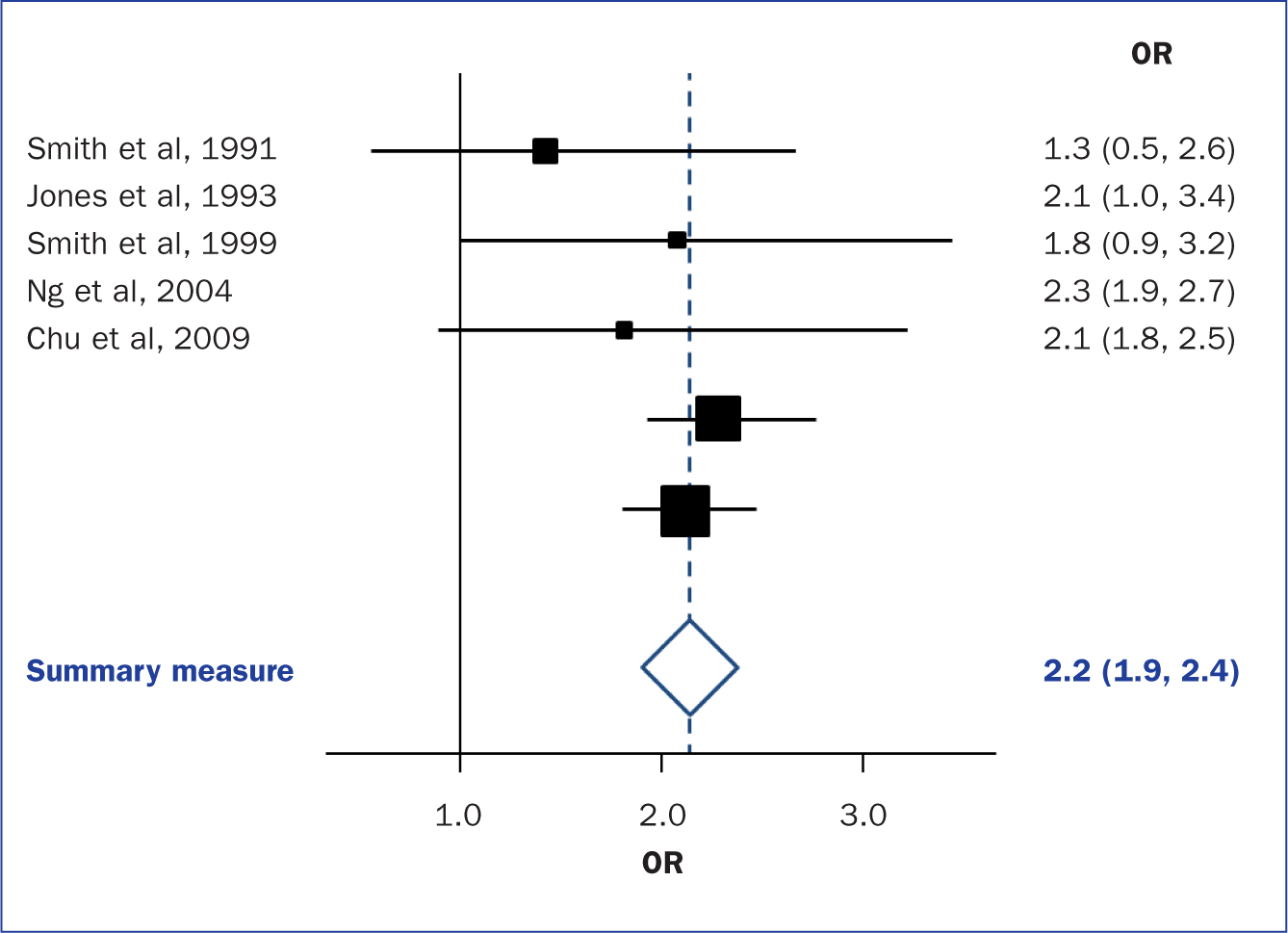

When the methods used and the analysis are similar or the same, such as in some RCTs, the results can be synthesised using a statistical approach called meta-analysis and presented using summary visualisations such as forest plots (or blobbograms) ( Figure 5 ). This can be done only if the results can be combined in a meaningful way.

Meta-analysis can be carried out using common statistical and data science software, such as the cross-platform ‘R’ ( https://www.r-project.org), or by using standalone software, such as Review Manager (RevMan) produced by the Cochrane community ( https://tinyurl.com/revman-5), which is currently developing a cross-platform version RevMan Web.

Carrying out a systematic review is a time-consuming process, that on average takes between 6 and 18 months and requires skill from those involved. Ideally, several reviewers will work on a review to reduce bias. Experts such as librarians should be consulted and included where possible in review teams to leverage their expertise.

Systematic reviews should present the state of the art (most recent/up-to-date developments) concerning a specific topic and aim to be systematic and reproducible. Reproducibility is aided by transparent reporting of the various stages of a review using reporting frameworks such as PRISMA for standardisation. A high-quality review should present a summary of a specific topic to a high standard upon which other professionals can base subsequent care decisions that increase the quality of evidence-based clinical practice.

- Systematic reviews remain one of the most trusted sources of high-quality information from which to make clinical decisions

- Understanding the components of a review will help practitioners to better assess their quality

- Many formal frameworks exist to help structure and report reviews, the use of which is recommended for reproducibility

- Experts such as librarians can be included in the review team to help with the review process and improve its quality

CPD reflective questions

- Where should high-quality qualitative research sit regarding the hierarchies of evidence?

- What background and expertise should those conducting a systematic review have, and who should ideally be included in the team?

- Consider to what extent inter-rater agreement is important in the screening process

- Become Involved |

- Give to the Library |

- Staff Directory |

- UNF Library

- Brooks College of Health

- Systematic Reviews

- Nursing Databases

- PICO(T) from Nutrition

- Search Strategy

What is a Systematic Review?

Types of systematic reviews, the prisma checklist and diagram, the systematic review process, structuring a systematic review article, finding the right journal for publication.

- Tools to Manage the Systematic Review Process

- Conducting a Literature Review This link opens in a new window

Call Us (904) 620-2615

Chat With Us Text Us (904) 507-4122 Email Us Schedule a Research Consultation

Visit us on social media!

PRISMA Documents

- PRISMA Checklist

- PRISMA Flow Diagram

Formulating a Research Question using PICO(T)

P=Population or problem or patient

- What are the characteristics of the patient or population? What is the condition?

I=Intervention or issue of interest

- What do you want to do with/for the patient or population?

C=Comparison

- What is the alternative to the intervention?

- What are the relevant outcomes?

A systematic review is a scientific study of all available evidence on a certain topic. It requires the most exhaustive literature search possible, not only in published literature, but also in gray literature. It may also require searches in disciplines outside the researchers primary area of study.

- Qualitative: In this type of systematic review, the results of relevant studies are summarized but not statistically combined.

- Quantitative: This type of systematic review uses statistical methods to combine the results of two or more studies.

- Meta-analysis: A meta-analysis uses statistical methods to integrate estimates of effect from relevant studies that are independent but similar and summarize them.

Anybody writing a systematic literature review should be familiar with the PRISMA statement . The PRISMA Statement is a document that consists of a 27-item checklist and a flow diagram . It is designed to guide authors on how to develop a systematic review and what to include when writing the review.

A protocol will include:

- Databases to be searched and additional sources (particularly for grey literature)

- Keywords to be used in the search strategy

- Limits applied to the search.

- Screening process

- Data to be extracted

- Summary of data to be reported

The essence of a systematic review lies in being systematic. A systematic review involves detailed scrutiny and analysis of a huge mass of literature. To ensure that your work is efficient and effective, you should follow a clear process :

1. Develop a research question

2. Define inclusion and exclusion criteria

3. Locate studies

4. Select studies

5. Assess study quality

6. Extract data

7. Analyze and present results

8. Interpret results

9. Update the review as needed

It is helpful to make notes at each stage. This will make it easier for you to write the review article.

A systematic review article follows the same structure as that of an original research article. It typically includes a title, abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and references.

Title: The title should accurately reflect the topic under review. Typically, the words “a systematic review” are a part of the title to make the nature of the study clear.

Abstract: A systematic review usually has a structured Abstract, with a short paragraph devoted to each of the following: background, methods, results, and conclusion.

Introduction : The Introduction summarizes the topic and explains why the systematic review was conducted. There might have been gaps in the existing knowledge or a disagreement in the literature that necessitated a review. The introduction should also state the purpose and aims of the review.

Methods: The Methods section is the most crucial part of a systematic review article. The methodology followed should be explained clearly and logically. The following components should be discussed in detail:

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Identification of studies

- Study selection

- Data extraction

- Quality assessment

- Data analysis

Results: The Results section should also be explained logically. You can begin by describing the search results, and then move on to the study range and characteristics, study quality, and finally discuss the effect of the intervention on the outcome.

Discussion: The Discussion should summarize the main findings from the review and then move on to discuss the limitations of the study and the reliability of the results. Finally, the strengths and weaknesses of the review should be discussed, and implications for current practice suggested.

References: The References section of a systematic review article usually contains an extensive number of references. You have to be very careful and ensure that you do not miss out on a single one. You can consider using reference management software to help you tackle the references effectively.

Enter your manuscript's title and abstract and other requested information and these systems will identify journals that are best suited for publishing. Each resource provides journal information and additional information such as impact factors, publishing model, time to publication, etc.

These tools search the journals of the individual publisher.

- Elsevier Journal Finder

- IEEE Publication Recommender

- Journal/Author Name Estimator (JANE) - PubMed

- Sage Journal Selector

- SpringerNature Journal Suggester

- Taylor & Francis Journal Suggestor

- Web of Science Manuscript Matcher You will need to create a free account to access Match.

- Wiley Journal Finder (Beta)

- A young researcher's guide to a systematic review

- How to conduct systematic literature reviews in management research: a guide in 6 steps and 14 decisions P. C. Sauer and S. Seuring, “How to conduct systematic literature reviews in management research: a guide in 6 steps and 14 decisions,” Review of managerial science, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 1899–1933, 2023, doi: 10.1007/s11846-023-00668-3

- << Previous: Search Strategy

- Next: PRISMA >>

- Last Updated: Oct 14, 2024 2:56 PM

- URL: https://libguides.unf.edu/nursing

Systematic Reviews

What is a systematic review.

- Steps of a Systematic Review

- Systematic Review Types

- Literature Reviews

Page Contents

Key characteristics of a systematic review, systematic reviews are not..., systematic reviews vs. narrative/literature reviews, standards and guidelines, appraising a systematic review, systematic review examples and further reading, medical library director.

Health Sciences Librarian

A systematic review is a ‘study about studies’ which focuses on a specific research question that it must try to answer by using explicit, transparent and reproducible methods to identify, critically appraise and synthesize results of similar studies to generate evidence-based findings. ( From Stephanie Roth’s Introduction to Systematic Reviews Course. June 2020 ).

Identify : review teams develop search strategies for multiple research databases and resources, and screen their findings against pre-specified eligibility criteria. , appraise : once all the evidence has been located and screened, review teams evaluate the quality of the evidence, assessing to understand where more research may be needed. , synthesize : finally, the review team brings together the different pieces of evidence, identifying trends, issues, or patterns in the data. the rigorous systematic review methodology makes these reviews a great tool for clinicians, educators, and stakeholders involved in decision-making or best practice recommendations. .

- Time-intensive: A typical systematic review can take 12-18 months to complete.

- Collaboration-intensive: The systematic review’s methodology requires multiple researchers to screen and evaluate evidence. A team of at least three is required.

- Protocol-based: Before beginning a systematic review, the team will pre-define their research question, expected outcomes, search strategy, and inclusion/exclusion criteria in a protocol. This helps mitigate potential bias or data manipulation.

- Research-question based: Systematic reviews are rooted in clear, focused questions. Many reviews will use the PICO framework or something similar to build their question.

- Exhaustive: The goal of a systematic review is to locate all of the available evidence for your question.

- Exclusive to medicine or healthcare: Systematic reviews are commissioned or developed for many different disciplines interested in making evidence-informed decisions.

- Exclusive to quantitative research: While many systematic reviews analyze studies that created quantitative data, qualitative and mixed methods reviews do exist and follow the systematic review methodology.

- The only “good” review type: Different types of reviews are helpful depending on your context and question. Meet with a librarian to discuss if a systematic review approach is right for your team.

- Exhausting (hopefully!): While systematic reviews can be time-intensive, the guiding methodology and opportunity for collaboration is invigorating to many researchers at all career levels.

*For more information how to conduct a narrative literature review see: https://medlib.belmont.edu/LitReviews

One of the nice things about systematic reviews is that there are well-established standards and guidelines for this research methodology.

JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis

- guides authors who wish to conduct systematic and scoping reviews following JBI methodologies

- Each chapter is devoted to the synthesis of different types of evidence to address different types of clinical and policy-related questions.

- Easy to apply, step-by-step guidance

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions

- The official guide that describes preparing and maintaining Cochrane systematic reviews

- includes guidance on the standard methods applicable to every review (planning a review, searching and selecting studies, data collection, risk of bias assessment, statistical analysis, GRADE and interpreting results)

Reporting Guidelines

- PRISMA-Checklist and Flow Diagram

- PRISMA-P extension for protocols

- PRISMA-S extension for search reporting

While systematic reviews are generally considered to be at the top of the “pyramid of evidence,” not all systematic reviews are created equal . Like any other research, they should be discussed, critiqued, and updated. Here are some tools for appraising systematic reviews:

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Systematic Review Checklists (CASP)

- Use these checklists to analyze how a systematic review was conducted.

Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Systematic Reviews (ROBIS)

- Use this tool to (1) assess relevance (optional), (2) identify concerns with the review process and (3) judge risk of bias for systematic reviews.

- Grant, M.J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 different review types and associated methodologies . Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26: 91-108. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Munn, Z., Stern, C., Aromataris, E. et al. What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences . BMC Med Res Methodol 18, 5 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0468-4

- Siddaway, A. P., Wood, A. M., & Hedges, L. V. (2019). How to do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses . Annual review of psychology, 70(1), 747-770.

- Allen, C., Walker, A. M., Premji, Z. A., Beauchemin-Turcotte, M. E., Wong, J., Soh, S., Hawboldt, G. S., Shinkaruk, K. S., & Archer, D. P. (2022). Preventing persistent postsurgical pain: A systematic review and component network meta-analysis. European journal of pain (London, England), 26(4), 771–785. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1915

- Hodder, R. K., O'Brien, K. M., Wyse, R. J., Tzelepis, F., Yoong, S., Stacey, F. G., & Wolfenden, L. (2024). Interventions for increasing fruit and vegetable consumption in children aged five years and under. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 9(9), CD008552. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008552.pub8

- Jefferies, D., McNally, S., Roberts, K., Wallace, A., Stunden, A., D'Souza, S., & Glew, P. (2018). The importance of academic literacy for undergraduate nursing students and its relationship to future professional clinical practice: A systematic review. Nurse education today, 60, 84–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.09.020

- Next: Steps of a Systematic Review >>

- Last Updated: Dec 6, 2024 12:52 PM

- URL: https://belmont.libguides.com/systematicreviews

- UWF Libraries

Evidence Based Nursing

- Types of Reviews

- What is Evidence -Based Practice & PICO

- PICO Widgets for Searching

- PubMed - Info & Tutorials

- Cochrane Library - Info & Tutorials

- Joanna Briggs Institute - Tutorial

- Finding the Evidence: Summaries & Clinical Guidlines

- Find Books & Background Resources

- Statistics and Data

- APA Formatting Guide

- Citation Managers - Zotero

- Library Presentations

What are the types of reviews?

As you begin searching through the literature for evidence, you will come across different types of publications. Below are examples of the most common types and explanations of what they are. Although systematic reviews and meta-analysis are considered the highest quality of evidence, not every topic will have an Systematic Review or Metanalysis.

Use the PRISMA Online Checklist to assess research and systematic reviews

Literature Review Examples

Remember, a literature review provides an overview of a topic. There may or may not be a method for how studies are collected or interpreted. Lit reviews aren't always obviously labeled "literature review"; they may be embedded within sections such as the introduction or background. You can figure this out by reading the article .

- Dance therapy for individuals with Parkinson's Disease Notice how the introduction and subheadings provide background on the topic and describe way it's important. Some studies are grouped together that convey a similar idea. Limitations of some studies are addressed as a way of showing the significance of the research topic.

- Ethical Issues Regarding Human Cloning: A Nursing Perspective Notice how this article is broken into several sections: background on human cloning, harms of cloning, and nursing issues in cloning. These are the themes of the different articles that were used in writing this literature review. Look at how the articles work together to form a cohesive piece of literature.

Systematic Review Examples

Systematic reviews address a clinical question. Reviews are gathered using a specific, defined set of criteria.

- Selection criteria is defined

- The words "Systematic Review" may appear int he title or abstract

- BTW -> Cochrane Reviews aka Systematic Reviews

- Additional reviews can be found by using a systematic review limit

- A Systematic Review of Animal-Assisted Therapy on Psychosocial Outcomes in People with Intellectual Disability

- The determinants and consequences of adult nursing staff turnover: a systematic review of systematic reviews

- Cochrane Library (Wiley) This link opens in a new window Over 5000 reviews of research on medical treatments, practices, and diagnostic tests are provided in this database. Cochrane Reviews is the premier resource for Evidence Based Practice.

- PubMed (NLM) This link opens in a new window PubMed comprises more than 22 million citations for biomedical literature from MEDLINE, life science journals, and online books.

Meta-Analysis Examples

Meta-analysis is a study that combines data from OTHER studies. All the studies are combined to argue whether a clinical intervention is statistically significant by combining the results from the other studies. For example, you want to examine a specific headache intervention without running a clinical trial. You can look at other articles that discuss your clinical intervention, combine all the participants from those articles, and run a statistical analysis to test if your results are significant. Guess what? There's a lot of math.

- Include the words "meta-analysis" or "meta analysis" in your keywords

- Meta-analyses will always be accompanied by a systematic review, but a systematic review may not have a meta-analysis

- See if the abstract or results section mention a meta-analysis

- Use databases like Cochrane or PubMed

- Exercise Interventions for Preventing Falls Among Older People in Care Facilities: A Meta-Analysis

- Acupuncture for the prevention of tension-type headache This is a systematic review that includes a meta-analysis. Check out the Abstract and Results for an example of what a meta-analysis looks like!

- << Previous: What is Evidence -Based Practice & PICO

- Next: Finding the Evidence >>

- Last Updated: Nov 20, 2024 9:23 AM

- URL: https://libguides.uwf.edu/EBN

An example of the use of systematic reviews to answer an effectiveness question

Affiliation.

- 1 College of Nursing, University of Saskatchewan.

- PMID: 12666642

- DOI: 10.1177/0193945902250036

Systematic reviews assist nurses, other health care providers, decision makers, and consumers in managing the explosion of health care information by synthesizing valid data and reporting the effects of interventions. Nurses are increasingly using systematic reviews to guide their practice and develop policy. The purpose of the article is to outline the steps involved in conducting a systematic review with examples taken from a systematic review titled "Strategies to Manage the Behavioral Symptoms Associated With Alzheimer's Disease." The steps of a systematic review include: (a) formulating a well-defined question, (b) developing relevance and validity tools, (c) conducting a comprehensive search to retrieve published and unpublished reports, (d) assessing the reports using relevance and validity tools, (e) data extraction, (f) synthesis of the findings, and (g) report writing. Understanding the steps involved in a systematic review will assist nurses in critically appraising reviews and in conducting their own reviews.

Publication types

- Systematic Review

- Nursing Methodology Research / methods*

- Reproducibility of Results

- Review Literature as Topic*

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Conducting integrative reviews: a guide for novice nursing researchers

Shannon dhollande, annabel taylor, silke meyer.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Shannon Dhollande, University of the Sunshine Coast, Caboolture Campus, Tallon Street, Cabolture, Queensland 4510, Australia. Email: [email protected]

Issue date 2021 Aug.

Integrative reviews within healthcare promote a holistic understanding of the research topic. Structure and a comprehensive approach within reviews are important to ensure the reliability in their findings.

This paper aims to provide a framework for novice nursing researchers undertaking integrative reviews.

Established methods to form a research question, search literature, extract data, critically appraise extracted data and analyse review findings are discussed and exemplified using the authors’ own review as a comprehensive and reliable approach for the novice nursing researcher undertaking an integrative literature review.

Providing a comprehensive audit trail that details how an integrative literature review has been conducted increases and ensures the results are reproducible. The use of established tools to structure the various components of an integrative review increases robustness and readers’ confidence in the review findings.

Implications for practice

Novice nursing researchers may increase the reliability of their results by employing a framework to guide them through the process of conducting an integrative review.

Keywords: integrative literature review, methodology research, nursing, research design

A literature review is a critical analysis of published research literature based on a specified topic ( Pluye et al., 2016 ). Literature reviews identify literature then examine its strengths and weaknesses to determine gaps in knowledge ( Pluye et al. 2016 ). Literature reviews are an integral aspect of research projects; indeed, many reviews constitute a publication in themselves ( Snyder, 2019 ). There are various types of literature reviews based largely on the type of literature sourced ( Cronin et al. 2008 ). These include systematic literature reviews, traditional, narrative and integrative literature reviews ( Snyder, 2019 ). Aveyard and Bradbury-Jones (2019) found more than 35 commonly used terms to describe literature reviews. Within healthcare, systematic literature reviews initially gained traction and widespread support because of their reproducibility and focus on arriving at evidence-based conclusions that could influence practice and policy development ( Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2015 ). Yet, it became apparent that healthcare-related treatment options needed to review broader spectrums of research for treatment options to be considered comprehensive, holistic and patient orientated ( Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2015 ). Stern et al. (2014) suggest that despite the focus in healthcare on quantitative research not all pertinent questions surrounding the provision of care can be answered from this approach. To devise solutions to multidimensional problems, all forms of trustworthy evidence need to be considered ( Stern et al. 2014 ).

Integrative reviews assimilate research data from various research designs to reach conclusions that are comprehensive and reliable ( Soares et al. 2014 ). For example, an integrative review considers both qualitative and quantitative research to reach its conclusions. This approach promotes the development of a comprehensive understanding of the topic from a synthesis of all forms of available evidence ( Russell, 2005 ; Torraco, 2005 ). The strengths of an integrative review include its capacity to analyse research literature, evaluate the quality of the evidence, identify knowledge gaps, amalgamate research from various research designs, generate research questions and develop theoretical frameworks ( Russell, 2005 ). Aveyard and Bradbury-Jones (2019) suggested that integrative reviews exhibit similar characteristics to systematic reviews and may therefore be regarded as rigorous.

Integrative reviews value both qualitative and quantitative research which are built upon differing epistemological paradigms. Both types of research are vital in developing the evidence base that guides healthcare provision ( Leppäkoski and Paavilainen, 2012 ). Therefore, integrative reviews may influence policy development as their conclusions have considered a broad range of appropriate literature ( Whittemore and Knafl, 2005 ). An integrative approach to evidence synthesis allows healthcare professionals to make better use of all available evidence and apply it to the clinical practice environment ( Souza et al. 2010 ). For example, Aveyard and Bradbury-Jones (2019) found in excess of 12 different types of reviews employed to guide healthcare practice. The healthcare profession requires both quantitative and qualitative forms of research to establish the robust evidence base that enables the provision of evidence-based patient-orientated healthcare.

Integrative reviews require a specific set of skills to identify and synthesise literature ( Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2010 ). There remains a paucity of literature that provides explicit guidance to novice nursing researchers on how to conduct an integrative review and importantly how to ensure the results and conclusions are both comprehensive and reliable. Furthermore, novice nursing researchers may receive little formal training to develop the skills required to generate a comprehensive integrative review ( Boote and Beile, 2005 ). Aveyard and Bradbury-Jones (2019) also emphasised the limited literature providing guidance surrounding integrative reviews. Therefore, novice nursing researchers need to rely on published guidance to assist them. In this regard this paper, using an integrative review conducted by the authors as a case study, aims to provide a framework for novice nursing researchers conducting integrative reviews.

Developing the framework

In conducting integrative reviews, the novice nursing researcher may need to employ a framework to ensure the findings are comprehensive and reliable ( Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2010 ; Snyder, 2019 ). A framework to guide novice nursing researchers in conducting integrative reviews has been adapted by the authors and will now be described and delineated. This framework used various published literature to guide its creation, namely works by Aveyard and Bradbury-Jones (2019) , Nelson (2014), Stern et al. (2014) , Whittemore and Knafl (2005) , Pluye et al. (2009) , Moher et al., (2009) and Attride-Stirling, (2001) . The suggested framework involves seven steps ( Figure 1 ).

Integrative review framework ( Cooke et al. 2012 ; Riva et al. 2012 ).

Step 1: Write the review question

The review question acts as a foundation for an integrative study ( Riva et al. 2012 ). Yet, a review question may be difficult to articulate for the novice nursing researcher as it needs to consider multiple factors specifically, the population or sample, the interventions or area under investigation, the research design and outcomes and any benefit to the treatment ( Riva et al. 2012 ). A well-written review question aids the researcher to develop their research protocol/design and is of vital importance when writing an integrative review.

To articulate a review question there are numerous tools available to the novice nursing researcher to employ. These tools include variations on the PICOTs template (PICOT, PICO, PIO), and the Spider template. The PICOTs template is an established tool for structuring a research question. Yet, the SPIDER template has gained acceptance despite the need for further research to determine its applicability to multiple research contexts ( Cooke et al., 2012 ). Templates are recommended to aid the novice nursing researcher in effectively delineating and deconstructing the various elements within their review question. Delineation aids the researcher to refine the question and produce more targeted results within a literature search. In the case study, the review question was to: identify, evaluate and synthesise current knowledge and healthcare approaches to women presenting due to intimate partner violence (IPV) within emergency departments (ED). This review objective is delineated in the review question templates shown in Table 1 .

Comparison of elements involved with a PICOTS and SPIDER review question.

( Cooke et al. 2012 ; Riva et al. 2012 ).

Step 2: Determine the search strategy

In determining a search strategy, it is important for the novice nursing researcher to consider the databases employed, the search terms, the Boolean operators, the use of truncation and the use of subject headings. Furthermore, Nelson (2014) suggests that a detailed description of the search strategy should be included within integrative reviews to ensure readers are able to reproduce the results.

The databases employed within a search strategy need to consider the research aim and the scope of information contained within the database. Many databases vary in their coverage of specific journals and associated literature, such as conference proceedings ( Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2010 ). Therefore, the novice nursing researcher should consult several databases when conducting their searches. For example, search strategies within the healthcare field may utilise databases such as Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Healthcare Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane Library, Science Direct, ProQuest, Web of Science, Scopus and PsychInfo ( Cronin et al. 2008 ). These databases among others are largely considered appropriate repositories of reliable data that novice researchers may utilise when researching within healthcare. The date in which the searches are undertaken should be within the search strategy as searches undertaken after this date may generate increased results in line with the publication of further studies.

Utilising an established template to generate a research question allows for the delineation of key elements within the question as seen above. These key elements may assist the novice nursing researcher in determining the search terms they employ. Furthermore, keywords on published papers may provide the novice nursing researcher with alternative search terms, synonyms and introduce the researcher to key terminology employed within their field ( Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2010 ). For example, within the case study undertaken the search terms included among others: ‘domestic violence’, ‘domestic abuse’, ‘intimate partner violence and/or abuse’. To refine the search to the correct healthcare environment the terms ‘emergency department’ and/or ‘emergency room’ were employed. To link search terms, the researcher should consider their use of Boolean operators ‘And’ ‘Or’ and ‘Not’ and their use of truncation ( Cronin et al. 2008 ). Truncation is the shortening of words which in literature searches may increase the number of search results. Medical subject headings (MeSH) or general subject headings should be employed where appropriate and within this case study the headings included ‘nursing’, ‘domestic violence’ and ‘intimate partner violence’.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria allow the novice nursing researcher to reduce and refine the search parameters and locate the specific data they seek. Appropriate use of inclusion and exclusion criteria permits relevant data to be sourced as wider searches can produce a large amount of disparate data, whereas a search that is too narrow may result in the omission of significant findings ( Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2010 ). The novice nursing researcher needs to be aware that generating a large volume of search results may not necessarily result in relevant data being identified. Within integrative reviews there is potential for a large volume of data to be sourced and therefore time and resources required to complete the review need to be considered ( Heyvaert et al. 2017 ). The analysis and refining of a large volume of data can become a labour-intensive exercise for the novice nursing researcher ( Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2010 ).

Stern et al. (2014) suggest various elements that should be considered within inclusion/exclusion criteria:

the type of studies included;

the topic under exploration;

the outcomes;

publication language;

the time period; and

the methods employed.

The use of limiters or exclusion criteria are an effective method to manage the amount of time it takes to undertake searches and limit the volume of research generated. Yet, exclusion criteria may introduce biases in the search results and should therefore be used with caution and to produce specific outcomes by the novice nursing researcher ( Hammerstrøm et al. 2017 ).

Whittemore and Knafl (2005) suggest that randomised controlled trials, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case control studies, cross sectional studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses should all be included within the search strategy. Therefore, there are no biases based on the type of publication sourced ( Hammerstrøm et al. 2017 ).

There should be no restriction on the sample size within the studies recognising that qualitative studies generally have smaller sample sizes, and to capture the breadth of research available. There was no restriction on the date of publication within the case study as quality literature was limited. Scoping widely is an important strategy within integrative reviews to produce comprehensive results. A manual citation search of the reference list of all sourced papers was also undertaken by a member of the research team.

Literature may be excluded if those papers were published in a language foreign to the researcher with no accepted translation available. Though limiting papers based on translation availability may introduce some bias, this does ensure the review remains free from translational errors and cultural misinterpretations. In the case study, research conducted in developing countries with a markedly different healthcare service and significant resource limitations were excluded due to their lack of generalisability and clinical relevance; though this may have introduced a degree of location bias ( Nelson, 2014 ).

A peer review of the search strategy by an individual who specialises in research data searches such as a research librarian may be a viable method in which the novice healthcare researcher can ensure the search strategy is appropriate and able to generate the required data. One such tool that a novice nurse may employ is the Peer Review of the Search Strategy (PRESS) checklist. A peer review of the caste study was undertaken by a research librarian. All recommendations were incorporated into the search strategy which included removing a full text limiter, and changes to the Boolean and proximity operators.

After the search strategy has been implemented the researcher removes duplicate results and screened the retrieved publications based on their titles and abstracts. A second screening was then undertaken based on the full text of retrieved publications to remove papers that were irrelevant to the research question. Full text copies should then be obtained for critical appraisal employing validated methods.

Step 3: Critical appraisal of search results

The papers identified within the search strategy should undergo a critical appraisal to determine if they are appropriate and of sufficient quality to be included within the review. This should be conducted or reviewed by a second member of the research team, which occurred within this case study. Any discrepancies were discussed until consensus was achieved. A critical appraisal allows the novice healthcare researcher to appraise the relevance and trustworthiness of a study and, therefore, determine its applicability to their research (CASP, 2013). There are several established tools a novice nurse can employ in which to structure their critical appraisal. These include the Scoring System for Mixed-Methods Research and Mixed Studies Reviews developed by Pluye et al. (2009) and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2018) Checklists.

The review undertaken by the authors employed the scoring system for mixed-methods research and mixed-studies reviews developed by Pluye et al. (2009) . This scoring system was specifically designed for reviews employing studies from various research designs and therefore was utilised with ease ( Table 2 ).

The scoring system for mixed-methods research and mixed-studies reviews ( Pluye et al. 2009 ).

Using the CASP checklist aids the novice nursing researcher to examine the methodology of identified papers to establish validity. This critical appraisal tool contains 10 items. These items are yes or no questions that assist the researcher to determine (a) if the results of the paper are valid, (b) what the results are and (c) if it is relevant in the context of their study. For example, the checklist asks the researcher to consider the presence of a clear statement surrounding the aims of the research, and to consider why and how the research is important in regard to their topic (CASP, 2013). This checklist supports the nurse researcher to assess the validity, results and significance of research, and therefore appropriately decide on its inclusion within the review ( Krainovich-Miller et al., 2009 ).

Step 4: Summarise the search results

A summary of the results generated by literature searches is important to exemplify how comprehensive the literature is or conversely to identify if there are gaps in research. This summary should include the number of, and type of papers included within the review post limiters, screening and critical appraisal of search results. For example, within the review detailed throughout this paper the search strategy resulted in the inclusion of 25 qualitative and six quantitative papers ( Bakon et al. 2019 ). Many papers provide a summary of their search results visually in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram ( Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2015 ). PRISMA is a method of reporting that enables readers to assess the robustness of the results ( Leclercq et al. 2019 ; Moher et al. 2009 ). PRISMA promotes the transparency of the search process by delineating various items within the search process ( Leclercq et al. 2019 ; Moher et al. 2009 ). Researchers may decide how rigorously they follow this process yet should provide a rationale for any deviations ( Leclercq et al. 2019 ; Moher et al, 2009 ). Figure 2 is an example of the PRISMA flow diagram as it was applied within the case study.

Example PRISMA flow diagram ( Bakon et al. 2019 ; Moher et al. 2009 ).

Step 5: Data extraction and reduction

Data can be extracted from the critically appraised papers identified through the search strategy employing extraction tables. Within the case study data were clearly delineated, as suggested by Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic (2010) , into extraction or comparison tables ( Table 3 ). These tables specify the authors, the date of publication, year of publication, site where the research was conducted and the key findings. Setting out the data into tables facilitates the comparison of these variables and aids the researcher to determine the appropriateness of the papers’ inclusion or exclusion within the review ( Whittemore and Knafl, 2005 ).

Example of a data extraction table.

Step 6: Analysis

Thematic analysis is widely used in integrative research ( Attride-Stirling, 2001 ). In this section we will discuss the benefits of employing a structured approach to thematic analysis including the formation of a thematic network. A thematic network is a visual diagram or depiction of the themes displaying their interconnectivity. Thematic analysis with the development of a thematic network is a way of identifying themes at various levels and depicting the observed relationships and organisation of these themes ( Attride-Stirling, 2001 ). There are numerous methods and tools available in which to conduct a thematic analysis that may be of use to the novice healthcare researcher conducting an integrative review. The approach used in a thematic analysis is important though a cursory glance at many literature reviews will reveal that many authors do not delineate the methods they employ. This includes the thematic analysis approach suggested by Thomas and Harden (2008) and the approach to thematic networking suggested by Attride-Stirling (2001) .

Thomas and Harden (2008) espouse a three-step approach to thematic analysis which includes: (a) coding, (b) organisation of codes into descriptive themes, and (c) the amalgamation of descriptive themes into analytical themes. The benefit of this approach lies in its simplicity and the ease with which a novice nurse researcher can apply the required steps. In contrast, the benefit of the approach suggested by Attride-Stirling (2001) lies in its ability to move beyond analysis and generate a visual thematic network which facilitates a critical interpretation and synthesis of the data.

Thematic networks typically depict three levels: basic themes, organising themes and global themes ( Attride-Stirling, 2001 ). The thematic network can then be developed. A thematic network is a visual depiction that appears graphically as a web like design ( Attride-Stirling, 2001 ). Thematic networks emphasise the relationships and interconnectivity of the network. It is an illustrative tool that facilitates interpretation of the data ( Attride-Stirling, 2001 ).

The benefits of employing a thematic analysis and networking within integrative reviews is the flexibility inherent within the approach, which allows the novice nursing researcher to provide a comprehensive accounting of the data ( Nowell et al. 2017 ). Thematic analysis is also an easily grasped form of data analysis that is useful for exploring various perspectives on specific topics and highlighting knowledge gaps ( Nowell et al. 2017 ). Thematic analysis and networking is also useful as a method to summarise large or diversified data sets to produce insightful conclusions ( Attride-Stirling, 2001 ; Nowell et al. 2017 ). The ability to assimilate data from various seemingly disparate perspectives may be challenging for the novice nursing researcher conducting an integrative review yet this integration of data by thematic analysis and networking was is integral.

To ensure the trustworthiness of results, novice nursing researchers need to clearly articulate each stage within the chosen method of data analysis ( Attride-Stirling, 2001 ; Nowell et al. 2017 ). The method employed in data analysis needs to be precise and exhaustively delineated ( Attride-Stirling, 2001 ; Nowell et al. 2017 ). Attride-Stirling (2001) suggests six steps within her methods of thematic analysis and networking. These steps include:

code material;

identify themes;

construct thematic network;

describe and explore the thematic network;

summarise thematic network findings; and

interpret patterns to identify implications.

In employing the approach suggested by Attride-Stirling (2001) within the case study the coding of specific findings within the data permitted the development of various themes ( Table 4 ). Inclusion of both quantitative and qualitative findings within the themes facilitated integration of the data which identified patterns and generated insights into the current care provided to IPV victims within ED.

Coding and theme formation.

Step 7: Conclusions and implications

A conclusion is important to remind the reader why the research topic is important. The researcher can then follow advice by Higginbottom (2015) who suggests that in drawing and writing research conclusions the researcher has an opportunity to explain the significance of the findings. The researcher may also need to explain these conclusions in light of the study limitations and parameters. Higginbottom (2015) emphasises that a conclusion is not a summary or reiteration of the results but a section which details the broader implications of the research and translates this knowledge into a format that is of use to the reader. The implications of the review findings for healthcare practice, for healthcare education and research should be considered.

Employing this structured and comprehensive framework within the case study the authors were able to determine that there remains a marked barrier in the provision of healthcare within the ED to women presenting with IPV-related injury. By employing an integrative approach multiple forms of literature were reviewed, and a considerable gap was identified. Therefore, further research may need to focus on the developing a structured healthcare protocol to aid ED clinicians to meet the needs of this vulnerable patient population.

Integrative reviews can be conducted with success when they follow a structured approach. This paper proposes a framework that novice nursing researchers can employ. Applying our stepped framework within an integrative review will strengthen the robustness of the study and facilitate its translation into policy and practice. This framework was employed by the authors to identify, evaluate and synthesise current knowledge and approaches of health professionals surrounding the care provision of women presenting due to IPV within emergency departments. The recommendations from the case study are currently being translated and implemented into the practice environment.

Key points for policy, practice and/or research

Integrative literature reviews are required within nursing to consider elements of care provision from a holistic perspective.

There is currently limited literature providing explicit guidance on how to undertake an integrative literature review.

Clear delineation of the integrative literature review process demonstrates how the knowledge base was understood, organised and analysed.

Nurse researchers may utilise this guidance to ensure the reliability of their integrative review.

Shannon Dhollande is a Lecturer, registered nurse and researcher. Her research explores the provision of emergency care to vulnerable populations.

Annabel Taylor is a Professorial Research Fellow at CQ University who with her background in social work explores methods of addressing gendered violence such as domestic violence.

Silke Meyer is an Associate Professor in Criminology and the Deputy Director of the Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre at Monash University.

Mark Scott is an Emergency Medical Consultant with a track record in advancing emergency healthcare through implementation of evidence-based healthcare.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics: Due to the nature of this article this article did not require ethical approval.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Shannon Dhollande, Lecturer, School of Nursing, Midwifery & Social Sciences, CQ University Brisbane, Australia.

Annabel Taylor, Professor, School of Nursing, Midwifery & Social Sciences, CQ University Brisbane, Australia.

Silke Meyer, Associate Professor, School of Social Sciences, Monash University, Australia.

Mark Scott, Emergency Consultant, Emergency Department, Caboolture Hospital, Australia.

Shannon Dhollande https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3181-7606

Silke Meyer https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3964-042X

- Attride-Stirling J. (2001) Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research 1(3): 385–405. [ Google Scholar ]

- Aveyard H, Bradbury-Jones C. (2019) An analysis of current practices in undertaking literature reviews in nursing: Findings from a focused mapping review and synthesis. BMC Medical Research Methodology 19(1): 1–9. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bakon S, Taylor A, Meyer S, et al. (2019) The provision of emergency healthcare for women who experience intimate partner violence: Part 1 An integrative review. Emergency Nurse 27: 19–25. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Boell S, Cecez-Kecmanovic D. (2010) Literature reviews and the Hermeneutic circle. Australian Academic & Research Libraries 41(2): 129–144. [ Google Scholar ]

- Boell S, Cecez-Kecmanovic D. (2015) On being systematic in literature reviews. Journal of Information Technology 30: 161–173. [ Google Scholar ]

- Boote D, Beile P. (2005) Scholars before researchers: On the centrality of the dissertation literature review in research preparation. Educational Researcher 34(6): 3–15. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. (2012) Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research 22(10): 1435–1443. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) (2018) CASP Checklists . casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists.

- Cronin P, Ryan F, Coughlan M. (2008) Undertaking a literature review: A step by step approach. British Journal of Nursing 17(1): 38–43. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hammerstrøm K, Wade A, Jørgensen A, et al. (2017) Searching for relevant studie. In: Heyvaert M, Hannes K, Onghena P. (eds) Using Mixed Methods Research Synthesis for Literature Reviews, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, pp. 69–112. [ Google Scholar ]

- Heyvaert M, Maes B, Onghena P, et al. (2017) Introduction to MMRS literature reviews. In: Heyvaert M, Hannes K, Onghena P. (eds) Using Mixed Methods Research Synthesis for Literature Reviews, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, pp. 1–22. [ Google Scholar ]

- Higginbottom G. (2015) Drawing conclusions from your research. In: Higginbottom G, Liamputtong P. (eds) Participatory Qualitative Research Methodologies in Health, London: SAGE, pp. 80–89. [ Google Scholar ]

- Krainovich-Miller B, Haber J, Yost J, et al. (2009) Evidence-based practice challenge: Teaching critical appraisal of systematic reviews and clinical practice guidelines to graduate students. Journal of Nursing Education 48(4): 186–195. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leclercq V, Beaudart C, Ajamieh S, et al. (2019) Meta-analyses indexed in PsycINFO had a better completeness of reporting when they mention PRISMA. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 115: 46–54. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leppäkoski T, Paavilainen E. (2012) Triangulation as a method to create a preliminary model to identify and intervene in intimate partner violence. Applied Nursing Research 25: 171–180. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nelson H. (2014) Systematic Reviews to Answer Health Care Questions, Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nowell L, Norris J, White D, et al. (2017) Thematic analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16(1): 1–13. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pluye P, Gagnon M, Griffiths F, et al. (2009) A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in mixed studies reviews. International Journal of Nursing Studies 46: 529–546. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pluye P, Hong Q, Bush P, et al. (2016) Opening up the definition of systematic literature review: The plurality of worldviews, methodologies and methods for reviews and syntheses. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 73: 2–5. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Riva JJ, Malik KM, Burnie SJ, et al. (2012) What is your research question? An introduction to the PICOT format for clinicians. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association 56(3): 167–171. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Russell C. (2005) An overview of the integrative research review. Progress in Transplantation 15(1): 8–13. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Snyder H. (2019) Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research 104: 333–339. [ Google Scholar ]

- Soares C, Hoga L, Peduzzi M, et al. (2014) Integrative review: Concepts and methods used in nursing. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP 48(2): 335–345. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Souza M, Silva M, Carvalho R. (2010) Integrative review: What is it? How to do it? Einstein 8(1): 102–106. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stern C, Jordan Z, McArthur A. (2014) Developing the review question and inclusion criteria. American Journal of Nursing 114(4): 53–56. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thomas J, Harden A. (2008) Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 8: 45. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Torraco R. (2005) Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Human Resource Development Review 4(3): 356–367. [ Google Scholar ]

- Whittemore R, Knafl K. (2005) The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing 52(5): 546–553. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (506.7 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Since their inception in the late 1970s, systematic reviews have gained influence in the health professions (Hanley and Cutts, 2013).Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are considered to be the most credible and authoritative sources of evidence available (Cognetti et al, 2015) and are regarded as the pinnacle of evidence in the various 'hierarchies of evidence'.

Lists strengths and weaknesses and examples of systematic reviews. Charting the landscape of graphical displays for meta-analysis and systematic reviews: A comprehensive review, ... PhD, RN, CNE is a professor of nursing at Ashland University Schar College of Nursing and Health Sciences in Ashland, OH.

The essence of a systematic review lies in being systematic. A systematic review involves detailed scrutiny and analysis of a huge mass of literature. To ensure that your work is efficient and effective, you should follow a clear process: 1. Develop a research question. 2. Define inclusion and exclusion criteria. 3. Locate studies . 4. Select ...

Systematic reviews that summarize the available information on a topic are an important part of evidence-based health care. There are both research and non-research reasons for undertaking a literature review. ... Examples of Systematic Reviews To Link Research and Quality Improvement. ... Nursing Research: principles and methods. 9th edition ...

Time-intensive: A typical systematic review can take 12-18 months to complete. Collaboration-intensive: The systematic review's methodology requires multiple researchers to screen and evaluate evidence. A team of at least three is required. Protocol-based: Before beginning a systematic review, the team will pre-define their research question, expected outcomes, search strategy, and inclusion ...

Implementing evidence into practice requires nurses to identify, critically appraise and synthesise research. This may require a comprehensive literature review: this article aims to outline the approaches and stages required and provides a working example of a published review. Literature reviews aim to answer focused questions to: inform professionals and patients of the best available ...

Below are examples of the most common types and explanations of what they are. Although systematic reviews and meta-analysis are considered the highest quality of evidence, not every topic will have an Systematic Review or Metanalysis. Use the PRISMA Online Checklist to assess research and systematic reviews. Print form

1 College of Nursing, University of Saskatchewan. PMID: 12666642 ... The purpose of the article is to outline the steps involved in conducting a systematic review with examples taken from a systematic review titled "Strategies to Manage the Behavioral Symptoms Associated With Alzheimer's Disease." The steps of a systematic review include: (a ...

Integrative review framework (Cooke et al. 2012; Riva et al. 2012).Step 1: Write the review question. The review question acts as a foundation for an integrative study (Riva et al. 2012).Yet, a review question may be difficult to articulate for the novice nursing researcher as it needs to consider multiple factors specifically, the population or sample, the interventions or area under ...