Revising the JBI quantitative critical appraisal tools to improve their applicability: an overview of methods and the development process

Affiliations.

- 1 JBI, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA, Australia.

- 2 Queen's Collaboration for Health Care Quality, Queen's University, Kingston, ON, Canada.

- 3 Czech National Centre for Evidence-Based Healthcare and Knowledge Translation (Cochrane Czech Republic; The Czech Republic [Middle European] Centre for Evidence-Based Healthcare: A JBI Centre of Excellence; Masaryk University GRADE Centre), Faculty of Medicine, Institute of Biostatistics and Analyses, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic.

- 4 The Nottingham Centre for Evidence-Based Healthcare: A JBI Centre of Excellence, School of Medicine, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK.

- 5 Centre for Health Informatics, Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

- PMID: 36121230

- DOI: 10.11124/JBIES-22-00125

JBI offers a suite of critical appraisal instruments that are freely available to systematic reviewers and researchers investigating the methodological limitations of primary research studies. The JBI instruments are designed to be study-specific and are presented as questions in a checklist. The JBI instruments have existed in a checklist-style format for approximately 20 years; however, as the field of research synthesis expands, many of the tools offered by JBI have become outdated. The JBI critical appraisal tools for quantitative studies (eg, randomized controlled trials, quasi-experimental studies) must be updated to reflect the current methodologies in this field. Cognizant of this and the recent developments in risk-of-bias science, the JBI Effectiveness Methodology Group was tasked with updating the current quantitative critical appraisal instruments. This paper details the methods and rationale that the JBI Effectiveness Methodology Group followed when updating the JBI critical appraisal instruments for quantitative study designs. We detail the key changes made to the tools and highlight how these changes reflect current methodological developments in this field.

Copyright © 2023 JBI.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Research Design*

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Critical Appraisal Toolkit (CAT) for assessing multiple types of evidence

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence: [email protected]

Contributor: Jennifer Kruse, Public Health Agency of Canada – Conceptualization and project administration

Series information

Scientific writing

Collection date 2017 Sep 7.

Healthcare professionals are often expected to critically appraise research evidence in order to make recommendations for practice and policy development. Here we describe the Critical Appraisal Toolkit (CAT) currently used by the Public Health Agency of Canada. The CAT consists of: algorithms to identify the type of study design, three separate tools (for appraisal of analytic studies, descriptive studies and literature reviews), additional tools to support the appraisal process, and guidance for summarizing evidence and drawing conclusions about a body of evidence. Although the toolkit was created to assist in the development of national guidelines related to infection prevention and control, clinicians, policy makers and students can use it to guide appraisal of any health-related quantitative research. Participants in a pilot test completed a total of 101 critical appraisals and found that the CAT was user-friendly and helpful in the process of critical appraisal. Feedback from participants of the pilot test of the CAT informed further revisions prior to its release. The CAT adds to the arsenal of available tools and can be especially useful when the best available evidence comes from non-clinical trials and/or studies with weak designs, where other tools may not be easily applied.

Introduction

Healthcare professionals, researchers and policy makers are often involved in the development of public health policies or guidelines. The most valuable guidelines provide a basis for evidence-based practice with recommendations informed by current, high quality, peer-reviewed scientific evidence. To develop such guidelines, the available evidence needs to be critically appraised so that recommendations are based on the "best" evidence. The ability to critically appraise research is, therefore, an essential skill for health professionals serving on policy or guideline development working groups.

Our experience with working groups developing infection prevention and control guidelines was that the review of relevant evidence went smoothly while the critical appraisal of the evidence posed multiple challenges. Three main issues were identified. First, although working group members had strong expertise in infection prevention and control or other areas relevant to the guideline topic, they had varying levels of expertise in research methods and critical appraisal. Second, the critical appraisal tools in use at that time focused largely on analytic studies (such as clinical trials), and lacked definitions of key terms and explanations of the criteria used in the studies. As a result, the use of these tools by working group members did not result in a consistent way of appraising analytic studies nor did the tools provide a means of assessing descriptive studies and literature reviews. Third, working group members wanted guidance on how to progress from assessing individual studies to summarizing and assessing a body of evidence.

To address these issues, a review of existing critical appraisal tools was conducted. We found that the majority of existing tools were design-specific, with considerable variability in intent, criteria appraised and construction of the tools. A systematic review reported that fewer than half of existing tools had guidelines for use of the tool and interpretation of the items ( 1 ). The well-known Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) rating-of-evidence system and the Cochrane tools for assessing risk of bias were considered for use ( 2 ), ( 3 ). At that time, the guidelines for using these tools were limited, and the tools were focused primarily on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized controlled trials. For feasibility and ethical reasons, clinical trials are rarely available for many common infection prevention and control issues ( 4 ), ( 5 ). For example, there are no intervention studies assessing which practice restrictions, if any, should be placed on healthcare workers who are infected with a blood-borne pathogen. Working group members were concerned that if they used GRADE, all evidence would be rated as very low or as low quality or certainty, and recommendations based on this evidence may be interpreted as unconvincing, even if they were based on the best or only available evidence.

The team decided to develop its own critical appraisal toolkit. So a small working group was convened, led by an epidemiologist with expertise in research, methodology and critical appraisal, with the goal of developing tools to critically appraise studies informing infection prevention and control recommendations. This article provides an overview of the Critical Appraisal Toolkit (CAT). The full document, entitled Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines Critical Appraisal Tool Kit is available online ( 6 ).

Following a review of existing critical appraisal tools, studies informing infection prevention and control guidelines that were in development were reviewed to identify the types of studies that would need to be appraised using the CAT. A preliminary draft of the CAT was used by various guideline development working groups and iterative revisions were made over a two year period. A pilot test of the CAT was then conducted which led to the final version ( 6 ).

The toolkit is set up to guide reviewers through three major phases in the critical appraisal of a body of evidence: appraisal of individual studies; summarizing the results of the appraisals; and appraisal of the body of evidence.

Tools for critically appraising individual studies

The first step in the critical appraisal of an individual study is to identify the study design; this can be surprisingly problematic, since many published research studies are complex. An algorithm was developed to help identify whether a study was an analytic study, a descriptive study or a literature review (see text box for definitions). It is critical to establish the design of the study first, as the criteria for assessment differs depending on the type of study.

Definitions of the types of studies that can be analyzed with the Critical Appraisal Toolkit*

Analytic study: A study designed to identify or measure effects of specific exposures, interventions or risk factors. This design employs the use of an appropriate comparison group to test epidemiologic hypotheses, thus attempting to identify associations or causal relationships.

Descriptive study: A study that describes characteristics of a condition in relation to particular factors or exposure of interest. This design often provides the first important clues about possible determinants of disease and is useful for the formulation of hypotheses that can be subsequently tested using an analytic design.

Literature review: A study that analyzes critical points of a published body of knowledge. This is done through summary, classification and comparison of prior studies. With the exception of meta-analyses, which statistically re-analyze pooled data from several studies, these studies are secondary sources and do not report any new or experimental work.

* Public Health Agency of Canada. Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines Critical Appraisal Tool Kit ( 6 )

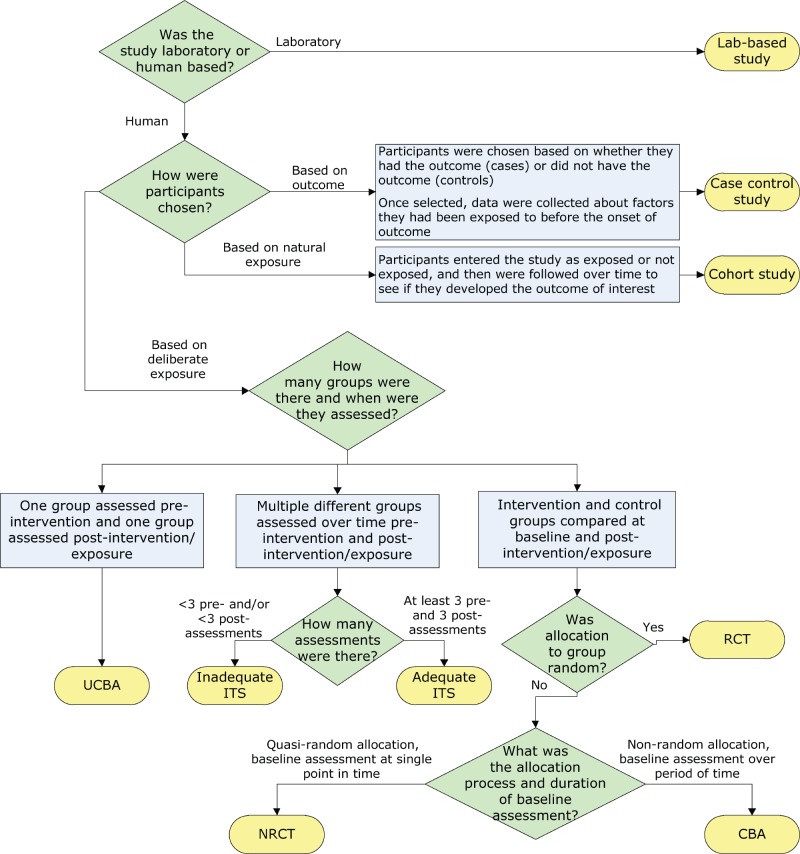

Separate algorithms were developed for analytic studies, descriptive studies and literature reviews to help reviewers identify specific designs within those categories. The algorithm below, for example, helps reviewers determine which study design was used within the analytic study category ( Figure 1 ). It is based on key decision points such as number of groups or allocation to group. The legends for the algorithms and supportive tools such as the glossary provide additional detail to further differentiate study designs, such as whether a cohort study was retrospective or prospective.

Figure 1. Algorithm for identifying the type of analytic study.

Abbreviations: CBA, controlled before-after; ITS, interrupted time series; NRCT, non-randomized controlled trial; RCT, randomized controlled trial; UCBA, uncontrolled before-after

Separate critical appraisal tools were developed for analytic studies, for descriptive studies and for literature reviews, with relevant criteria in each tool. For example, a summary of the items covered in the analytic study critical appraisal tool is shown in Table 1 . This tool is used to appraise trials, observational studies and laboratory-based experiments. A supportive tool for assessing statistical analysis was also provided that describes common statistical tests used in epidemiologic studies.

Table 1. Aspects appraised in analytic study critical appraisal tool.

The descriptive study critical appraisal tool assesses different aspects of sampling, data collection, statistical analysis, and ethical conduct. It is used to appraise cross-sectional studies, outbreak investigations, case series and case reports.

The literature review critical appraisal tool assesses the methodology, results and applicability of narrative reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

After appraisal of individual items in each type of study, each critical appraisal tool also contains instructions for drawing a conclusion about the overall quality of the evidence from a study, based on the per-item appraisal. Quality is rated as high, medium or low. While a RCT is a strong study design and a survey is a weak design, it is possible to have a poor quality RCT or a high quality survey. As a result, the quality of evidence from a study is distinguished from the strength of a study design when assessing the quality of the overall body of evidence. A definition of some terms used to evaluate evidence in the CAT is shown in Table 2 .

Table 2. Definition of terms used to evaluate evidence.

* Considered strong design if there are at least two control groups and two intervention groups. Considered moderate design if there is only one control and one intervention group

Tools for summarizing the evidence

The second phase in the critical appraisal process involves summarizing the results of the critical appraisal of individual studies. Reviewers are instructed to complete a template evidence summary table, with key details about each study and its ratings. Studies are listed in descending order of strength in the table. The table simplifies looking across all studies that make up the body of evidence informing a recommendation and allows for easy comparison of participants, sample size, methods, interventions, magnitude and consistency of results, outcome measures and individual study quality as determined by the critical appraisal. These evidence summary tables are reviewed by the working group to determine the rating for the quality of the overall body of evidence and to facilitate development of recommendations based on evidence.

Rating the quality of the overall body of evidence

The third phase in the critical appraisal process is rating the quality of the overall body of evidence. The overall rating depends on the five items summarized in Table 2 : strength of study designs, quality of studies, number of studies, consistency of results and directness of the evidence. The various combinations of these factors lead to an overall rating of the strength of the body of evidence as strong, moderate or weak as summarized in Table 3 .

Table 3. Criteria for rating evidence on which recommendations are based.

A unique aspect of this toolkit is that recommendations are not graded but are formulated based on the graded body of evidence. Actions are either recommended or not recommended; it is the strength of the available evidence that varies, not the strength of the recommendation. The toolkit does highlight, however, the need to re-evaluate new evidence as it becomes available especially when recommendations are based on weak evidence.

Pilot test of the CAT

Of 34 individuals who indicated an interest in completing the pilot test, 17 completed it. Multiple peer-reviewed studies were selected representing analytic studies, descriptive studies and literature reviews. The same studies were assigned to participants with similar content expertise. Each participant was asked to appraise three analytic studies, two descriptive studies and one literature review, using the appropriate critical appraisal tool as identified by the participant. For each study appraised, one critical appraisal tool and the associated tool-specific feedback form were completed. Each participant also completed a single general feedback form. A total of 101 of 102 critical appraisals were conducted and returned, with 81 tool-specific feedback forms and 14 general feedback forms returned.

The majority of participants (>85%) found the flow of each tool was logical and the length acceptable but noted they still had difficulty identifying the study designs ( Table 4 ).

Table 4. Pilot test feedback on user friendliness.

* Number of tool-specific forms returned for total number of critical appraisals conducted

The vast majority of the feedback forms (86–93%) indicated that the different tools facilitated the critical appraisal process. In the assessment of consistency, however, only four of ten analytic studies appraised (40%), had complete agreement on the rating of overall study quality by participants, the other six studies had differences noted as mismatches. Four of the six studies with mismatches were observational studies. The differences were minor. None of the mismatches included a study that was rated as both high and low quality by different participants. Based on the comments provided by participants, most mismatches could likely have been resolved through discussion with peers. Mismatched ratings were not an issue for the descriptive studies and literature reviews. In summary, the pilot test provided useful feedback on different aspects of the toolkit. Revisions were made to address the issues identified from the pilot test and thus strengthen the CAT.

The Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines Critical Appraisal Tool Kit was developed in response to the needs of infection control professionals reviewing literature that generally did not include clinical trial evidence. The toolkit was designed to meet the identified needs for training in critical appraisal with extensive instructions and dictionaries, and tools applicable to all three types of studies (analytic studies, descriptive studies and literature reviews). The toolkit provided a method to progress from assessing individual studies to summarizing and assessing the strength of a body of evidence and assigning a grade. Recommendations are then developed based on the graded body of evidence. This grading system has been used by the Public Health Agency of Canada in the development of recent infection prevention and control guidelines ( 5 ), ( 7 ). The toolkit has also been used for conducting critical appraisal for other purposes, such as addressing a practice problem and serving as an educational tool ( 8 ), ( 9 ).

The CAT has a number of strengths. It is applicable to a wide variety of study designs. The criteria that are assessed allow for a comprehensive appraisal of individual studies and facilitates critical appraisal of a body of evidence. The dictionaries provide reviewers with a common language and criteria for discussion and decision making.

The CAT also has a number of limitations. The tools do not address all study designs (e.g., modelling studies) and the toolkit provides limited information on types of bias. Like the majority of critical appraisal tools ( 10 ), ( 11 ), these tools have not been tested for validity and reliability. Nonetheless, the criteria assessed are those indicated as important in textbooks and in the literature ( 12 ), ( 13 ). The grading scale used in this toolkit does not allow for comparison of evidence grading across organizations or internationally, but most reviewers do not need such comparability. It is more important that strong evidence be rated higher than weak evidence, and that reviewers provide rationales for their conclusions; the toolkit enables them to do so.

Overall, the pilot test reinforced that the CAT can help with critical appraisal training and can increase comfort levels for those with limited experience. Further evaluation of the toolkit could assess the effectiveness of revisions made and test its validity and reliability.

A frequent question regarding this toolkit is how it differs from GRADE as both distinguish stronger evidence from weaker evidence and use similar concepts and terminology. The main differences between GRADE and the CAT are presented in Table 5 . Key differences include the focus of the CAT on rating the quality of individual studies, and the detailed instructions and supporting tools that assist those with limited experience in critical appraisal. When clinical trials and well controlled intervention studies are or become available, GRADE and related tools from Cochrane would be more appropriate ( 2 ), ( 3 ). When descriptive studies are all that is available, the CAT is very useful.

Table 5. Comparison of features of the Critical Appraisal Toolkit (CAT) and GRADE.

Abbreviation: GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

The Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines Critical Appraisal Tool Kit was developed in response to needs for training in critical appraisal, assessing evidence from a wide variety of research designs, and a method for going from assessing individual studies to characterizing the strength of a body of evidence. Clinician researchers, policy makers and students can use these tools for critical appraisal of studies whether they are trying to develop policies, find a potential solution to a practice problem or critique an article for a journal club. The toolkit adds to the arsenal of critical appraisal tools currently available and is especially useful in assessing evidence from a wide variety of research designs.

Authors’ Statement

DM – Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data collection and curation and writing – original draft, review and editing

TO – Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data collection and curation and writing – original draft, review and editing

KD – Conceptualization, review and editing, supervision and project administration

Acknowledgements

We thank the Infection Prevention and Control Expert Working Group of the Public Health Agency of Canada for feedback on the development of the toolkit, Lisa Marie Wasmund for data entry of the pilot test results, Katherine Defalco for review of data and cross-editing of content and technical terminology for the French version of the toolkit, Laurie O’Neil for review and feedback on early versions of the toolkit, Frédéric Bergeron for technical support with the algorithms in the toolkit and the Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control of the Public Health Agency of Canada for review, feedback and ongoing use of the toolkit. We thank Dr. Patricia Huston, Canada Communicable Disease Report Editor-in-Chief, for a thorough review and constructive feedback on the draft manuscript.

Conflict of interest: None.

Funding: This work was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

- 1. Katrak P, Bialocerkowski AE, Massy-Westropp N, Kumar S, Grimmer KA. A systematic review of the content of critical appraisal tools. BMC Med Res Methodol 2004. Sep;4:22. 10.1186/1471-2288-4-22 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. GRADE Working Group. Criteria for applying or using GRADE. www.gradeworkinggroup.org [Accessed July 25, 2017].

- 3. Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://handbook.cochrane.org

- 4. Khan AR, Khan S, Zimmerman V, Baddour LM, Tleyjeh IM. Quality and strength of evidence of the Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guidelines. Clin Infect Dis 2010. Nov;51(10):1147–56. 10.1086/656735 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Public Health Agency of Canada. Routine practices and additional precautions for preventing the transmission of infection in healthcare settings. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/nois-sinp/guide/summary-sommaire/tihs-tims-eng.php [Accessed December 4, 2015].

- 6. Public Health Agency of Canada. Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines Critical Appraisal Tool Kit. http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2014/aspc-phac/HP40-119-2014-eng.pdf [Accessed December 4, 2015].

- 7. Public Health Agency of Canada. Hand hygiene practices in healthcare settings. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/infectious-diseases/nosocomial-occupational-infections/hand-hygiene-practices-healthcare-settings.html [Accessed December 4, 2015].

- 8. Ha S, Paquette D, Tarasuk J, Dodds J, Gale-Rowe M, Brooks JI et al. A systematic review of HIV testing among Canadian populations. Can J Public Health 2014. Jan;105(1):e53–62. 10.17269/cjph.105.4128 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Stevens LK, Ricketts ED, Bruneau JE. Critical appraisal through a new lens. Nurs Leadersh (Tor Ont) 2014. Jun;27(2):10–3. 10.12927/cjnl.2014.23843 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Lohr KN. Rating the strength of scientific evidence: relevance for quality improvement programs. Int J Qual Health Care 2004. Feb;16(1):9–18. 10.1093/intqhc/mzh005 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Crowe M, Sheppard L. A review of critical appraisal tools show they lack rigor: alternative tool structure is proposed. J Clin Epidemiol 2011. Jan;64(1):79–89. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.008 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Young JM, Solomon MJ. How to critically appraise an article. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009. Feb;6(2):82–91. 10.1038/ncpgasthep1331 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. 9 th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. Chapter XX, Literature reviews: Finding and critiquing the evidence p. 94-125. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (348.4 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

VIDEO